Negotiator Bo Gritz reports Vicki Weaver’s death

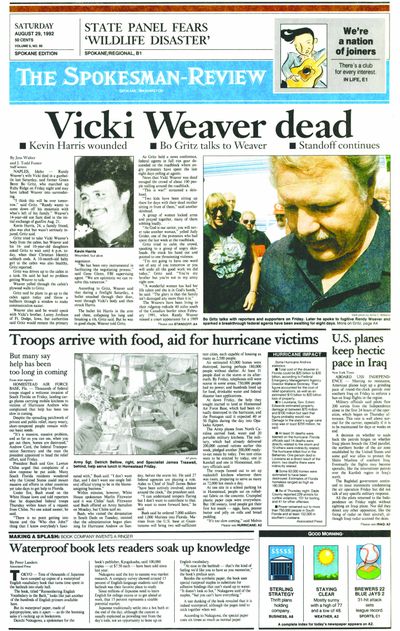

NAPLES, Idaho – Randy Weaver’s wife Vicki died in a gunbattle last Saturday, said former Green Beret Bo Gritz, who marched up Ruby Ridge on Friday night and may have talked Weaver into surrendering.

“I think this will be over tomorrow,” said Gritz. “Randy wants to come down off his mountain with what’s left of his family.” Weaver’s 14-year-old son Sam died in the initial exchange of gunfire Aug. 21.

Kevin Harris, 24, a family friend, also was shot but wasn’t seriously injured, Gritz said.

Gritz tried to take Vicki Weaver’s body from the cabin, but Weaver and his 16- and 10-year-old daughters asked Gritz to wait until 6 p.m. today, when their Christian Identity sabbath ends. A 10-month-old baby girl in the cabin was also healthy, Gritz reported.

Gritz was driven up to the cabin in a tank. He said he had no problem getting Weaver to talk.

Weaver yelled through the cabin’s plywood walls to Gritz.

Gritz said he plans to go up to the cabin again today and throw a bullhorn through a window to make communication easier.

Weaver also said he would speak with Vicki’s brother, Lanny Jordison of Ft. Dodge, Iowa, but authorities said Gritz would remain the primary negotiator.

“Bo has been very instrumental in facilitating the negotiating process,” said Gene Glenn, FBI supervising agent. “We are optimistic we can resolve this tomorrow.”

According to Gritz, Weaver said that during a firefight Saturday, a bullet smashed through their door, went through Vicki’s body and then struck Harris.

The bullet hit Harris in the arm and chest, collapsing his lung and breaking a rib, Gritz said. But he was in good shape, Weaver told Gritz.

As Gritz held a news conference, federal agents in full riot gear descended on the roadblock where angry protesters have spent the last eight days yelling at agents.

News that Vicki Weaver was dead enraged the crowd of about 100 people milling around the roadblock.

“This is war!” screamed a skinhead.

“Two kids have been sitting up there for days with their dead mother sitting in front of them,” said another skinhead.

A group of women locked arms and prayed together, many of them sobbing loudly.

“As God is our savior, you will never take another woman,” yelled Judy Grider, one of the protesters who had spent the last week at the roadblock.

Gritz tried to calm the crowd, speaking to a group of angry skinheads. He stuck his hand out and pointed to one threatening violence.

“I’m not going to have one word out of any of you tomorrow or you will undo all the good work we did today,” Gritz said. “You’re my brother but you’re not in my army right now.

“A wonderful woman has had her life taken and she is in God’s hands,” he said. “The glory is that the family isn’t damaged any more than it is.”

The Weavers have been living in their ridgetop redoubt 40 miles south of the Canadian border since February 1991, when Randy Weaver missed a court appearance for a 1989 federal weapons violation.

News of the breakthrough in the eight-day standoff came about 10 p.m., when the FBI summoned Vicki Weaver’s family and the family of Harris.

They were taken past the federal roadblock and up the road toward the cabin. News of Vicki Weaver’s death came about 30 minutes later.

After trying for two days to get federal agents to take him to the remote cabin, Gritz – the controversial third-party presidential candidate – finally got his wish around 8 p.m. Friday.

“If they let me talk to him, I can finish this thing,” Gritz said earlier in the day.

At first, weary federal agents appeared skeptical that Gritz could be of any help. Earlier in the day, he’d tried to make a citizen’s arrest of Gov. Cecil Andrus and the federal authorities heading up the siege.

But after pleas from Weaver’s family and an afternoon meeting with the Vietnam veteran, FBI agents allowed Gritz up to the cabin. Until then, Weaver would only respond to the voice of his sister, Marnis Joy.

“We asked the FBI to let him (Gritz) go in,” said Lanny Jordison earlier in the day. “He seemed like he could make a difference.”

Gritz’ mission was only one of the bizarre events on a day that saw fringe groups play dueling leaflets and try to arrest Gov. Cecil Andrus and other federal and local authorities.

“If they let me go up there, I can almost guarantee this craziness will be over,” said Gritz, who remembers Weaver from Army Special Forces.

But U.S. Marshal for Idaho Mike Johnson said Weaver had only asked to talk to his sister. Progress had been slow but steady in their efforts to get Weaver, his family and Harris out of the Cabin.

They’ve been under siege by federal agents since the Aug. 21 gunfight which also killed deputy U.S. marshal William Degan, 42.

The siege started when deputy U.S. marshals were conducting one of the routine surveillance of the cabin.

At the base of the hill, the pack of people decrying Weaver’s treatment grew steadily and authorities feared the weekend would bring even more.

At one point, 83 cars from 10 states – and one with a license plate from Heaven – were strung along the narrow dirt road that cuts in front of Ruby Ridge, where Weaver is holed up with his family.

“There are people coming from all over the country for this,” said Mike Bartee, a constitutionalist from Oregon, who came to see his hero, Gritz.

“Randy Weaver is not a criminal,” Gritz said. “He is a man trying to protect his family who needs some help.”

Staff writer Susan Drumheller contributed to this report.