Despite recall notices, many vehicles don’t get repaired

WASHINGTON – Timothy Michaud died last May after falling from the tailgate of a Chevrolet pickup and suffering severe head injuries.

The 19-year-old from Maine never knew that General Motors Corp. had recalled the pickup two months earlier because the tailgate cables could corrode and snap. At the time of the accident, Michaud’s employer – who owned the used 2000 pickup – hadn’t received a recall notice, said Stephen Schwarz, an attorney for the Michaud family.

The pickup was one of the millions of recalled vehicles that go unrepaired each year. Sometimes, vehicle owners are at fault for not getting repairs. But some safety experts say automakers and federal regulators share the blame because they haven’t developed a better system to track whether a vehicle has in fact been repaired.

“California requires that whenever you go in for registration, they check what emissions recalls have been done,” said Clarence Ditlow of the Center for Auto Safety, an advocacy group. “If you can do it for emissions recalls, you can do it for safety recalls.”

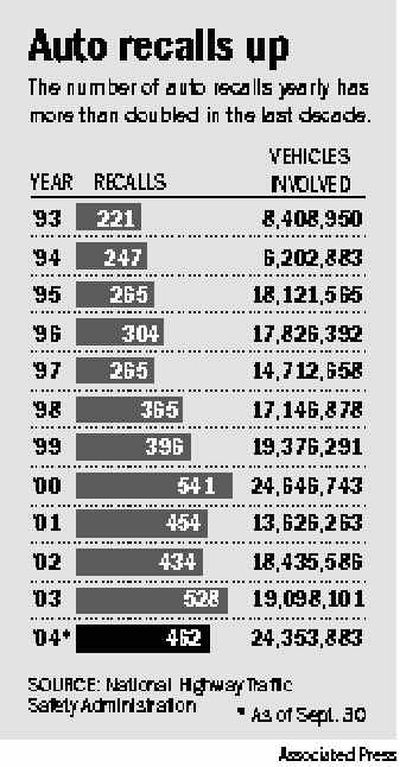

Kathy DeMeter, director of defect investigations for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, said around 72 percent of recalled vehicles are repaired each year. That means that in 2003, when 19.1 million vehicles were recalled, about 5.3 million vehicles weren’t repaired.

While the repair rate is lower than the NHTSA would like, DeMeter said it’s up from a decade ago, when the average was 65 percent. She also said it’s higher than other auto-related products. Only 35 percent of recalled tires and 45 percent of recalled child seats are repaired because it’s harder to track the owners.

“People are becoming more aware of safety, and manufacturers are doing a better job of notifying them,” DeMeter said.

Automakers are required to give the NHTSA repair data for six quarters after they send a notification letter to owners. If repair rates are exceptionally low, DeMeter said, the NHTSA will occasionally require an automaker to send a second notice.

Ford Motor Co. has one of the highest repair rates – around 80 percent – because it sends multiple letters to owners instead of the one letter the NHTSA requires, DeMeter said. Charlie Kopeika, Ford’s manager of recalls, said the company will send up to five letters and postcards over two years.

Ford buys registration data from states to track down vehicles even after they’ve changed owners. Despite those efforts, a certain percentage of owners are never found, Kopeika said. The oldest Ford recall that the NHTSA is still tracking, a 1999 recall of Windstar minivans with a fuel tank problem, shows 3,253 of the 83,052 owners were never reached. Automakers don’t have to contact owners if the vehicles have been moved abroad.

Repair rates for newer vehicles are generally higher. As of Sept. 30, one year after they were recalled because of a fuel tank defect, 90.6 percent of 2004 Toyota Sienna minivans had been repaired. By comparison, the repair rate for older models of the Volkswagen New Beetle was 56.7 percent on Sept. 30, a year after they were recalled because of faulty brake lights.

Federal law has required automakers to provide free repairs for safety-related defects since 1966. Since then, more than 366 million vehicles have been recalled in the United States.

Automakers won’t reveal how much they spend on recalls, but the costs go into the billions. The Automotive Industry Action Group, a Michigan-based advocacy group for the auto industry, said automakers can save $25 million for every 10 percent decrease in the time it takes to find a defect. Earlier this year, GM cited high recall costs as a drag on its second-quarter profits.

Despite the expense of providing repairs, Kopeika said manufacturers can be trusted to make sure owners know about recalls.

“It’s a huge customer satisfaction issue,” Kopeika said.

Some safety advocates aren’t so sure. Joan Claybrook, who led the NHTSA during the Carter administration and now is the president of the consumer group Public Citizen, said manufacturers could do a lot more to improve repair rates, starting with the wording of notification letters.

“Manufacturers like to tone down the letter,” Claybrook said. “If the consumer isn’t given a red hot alert, then they’re less likely to respond.”

A letter GM sent to pickup owners in April included a warning in bold print not to sit or stand on the tailgate until the cables were replaced. Once the letter was sent, GM needed to get millions of parts to dealers, so repairs didn’t begin until mid-September. As of Sept. 30, fewer than 1 percent of the 3.4 million recalled vehicles had been repaired.

In the meantime, Michaud’s family brought a claim for wrongful death against the automaker; the claim is being investigated by GM and the NHTSA, Schwarz said. He said the family didn’t wish to comment further.

Claybrook said manufacturers also should be less resistant to reporting injuries and deaths. One extreme case is Mitsubishi Motors Corp., which still is grappling with a 25-year recall cover-up scam. But other manufacturers are pressuring the NHTSA in court to prevent it from publicizing data on deaths and injuries.

Claybrook said the NHTSA also should stop certain practices, such as allowing manufacturers to recall vehicles only in certain regions. The NHTSA doesn’t have the capacity to keep track of repairs to individual vehicles, she said, but should list recalls needed by vehicle identification number and publicize its system so owners know where to look for recall information.