Rethinking the system

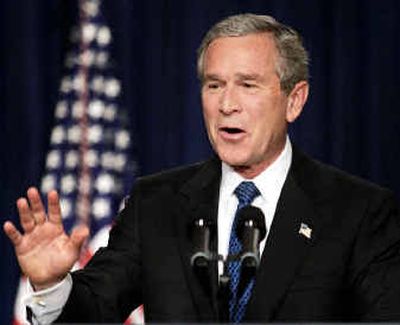

WASHINGTON — At the top of President Bush’s legislative agenda for next year is an overhaul of Social Security. He wants to let younger workers divert some of their Social Security payroll taxes into personal investment accounts similar to a 401(k).

Bush says creating the accounts would help shore up the program’s finances. The president has not provided details about how private accounts would be structured or financed. He made the overhaul a campaign promise in 2000.

Here, in question and answer form, is a look at the issue:

Q: When would Congress vote on whether to remake Social Security?

A: Supporters want a vote by the end of next summer. Lawmakers are expected to start on the issue when a new session convenes in late January. Bush’s top strategist, Karl Rove, told Republican lawmakers at a Wednesday retreat in Virginia that legislation is an early priority. Officials familiar with the closed-door meeting said administration experts on Social Security are still compiling options for the president to consider, and have yet to present him with material to review.

Q: Why are changes needed to Social Security?

A: Social Security is a pay-as-you-go system, with current benefits funded by the 12.4 percent in payroll taxes paid by workers and employers. The large baby boom generation will strain the system, which will start paying out more in benefits than it collects in taxes in 2018, according to the Social Security Board of Trustees. Without any changes, Social Security in 2042 will be able to cover only about 73 percent of benefits owed.

Q: Will creating personal investment accounts fix the funding problem?

A: No. Other changes will be needed, such as raising taxes, raising the retirement age, cutting benefits or a combination. The retirement age now is 65 and four months, and is rising two months each year until it reaches 67.

Many proposals to add private accounts reduce promised benefits by changing the way base benefits are calculated. Investments are supposed to make up the difference.

To help finance the change, some lawmakers say they will consider raising or removing the limit on income subject to the payroll tax. The maximum level of earnings taxed is $87,900 now; it will rise to $90,000 next year.

Q: Will raising taxes, raising the retirement age or cutting benefits shore up funding without adding investment accounts?

A: Yes.

Q: Then why create investment accounts?

A: It’s a philosophical debate. Supporters, generally Republicans, see an opportunity to create what they view as a better system that does not rely on demographics. They say that payroll taxes are people’s hard-earned money and that Social Security does not provide them much of an investment return. Supporters think workers should be able to build a nest egg and pass it on to survivors. Younger people tend to be more supportive of Social Security investment accounts.

Q: How do opponents of the accounts view Social Security?

A: Opponents, who tend to be Democrats, say Social Security is an insurance program, not a wealth-generating program, that provides a guaranteed, risk-free benefit. It was created during the Great Depression to help keep elderly people out of poverty, with a generation of workers paying for retirees’ benefits. Opponents also say the investment accounts can be risky.

AARP, a powerful lobbying group representing older people, opposes the investment accounts if payroll taxes are diverted into them.

Q: What about money in the Social Security trust fund?

A: The trust fund does not really contain money. Social Security today collects more in taxes than it pays out in benefits. The extra money is used to buy Treasury bonds from the government. The government then spends the money as part of its general revenue.

Starting in 2018, when payroll taxes will not completely cover promised benefits, the bonds will be cashed in, with the government essentially repaying the money it already had spent. That will provide revenue to pay benefits to 2042.

Q: How would the investment accounts generally work?

A: Younger workers could put a portion of their payroll taxes in a special account. Like a 401(k) plan, workers could choose from several investment options, such as a mix of stocks and bonds. Retirees could not participate.

Q: Then how would retirees’ benefits be funded if payroll taxes are getting diverted into accounts?

A: That is a problem. Such transition costs are expected to be around $2 trillion, depending on the size of the accounts. Supporters say money could be borrowed. Some are open to raising or removing the limit on income subject to the payroll tax. Opponents point to record budget deficits — $413 billion in 2004 — and are against borrowing.