Scrambled signals

NEW YORK — On a trip on the Tokyo subway last year, almost everyone ignored the young man talking on one wireless phone, messaging with another and juggling a third.

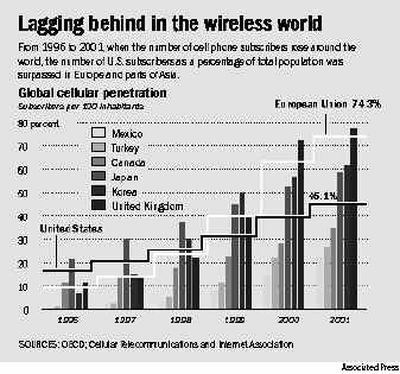

Such cell phone overload would almost certainly get noticed in the United States, which lags the rest of the developed world in wireless use.

An estimated 57 percent of the U.S. population chats on wireless phones — not much greater than the percentage of wireless phone users in much poorer Jamaica, where 54 percent of the people have mobile phones, according to the International Telecommunications Union.

By comparison, in Hong Kong there are 105.75 mobile subscribers for every 100 inhabitants. In Taiwan, there are 110.

Sprint Corp.’s $35 billion deal this week to buy Nextel Communications Inc. is likely to spark another round of price wars and handset giveaways in the United States, but it will take more than industry consolidation and aggressive marketing to increase use.

Why? The reasons range from credit checks to network quality to coverage areas.

Wireless networks elsewhere are simply better than those in the United States, said Albert Lin, an analyst at American Technology Research.

“For a long time, the U.S. had way too many networks being supported by not enough investment,” he said. “The quality of U.S. networks is only now coming close to the quality you would see in major European and Asian markets.”

Not that the European model was perfect: Companies there paid $125 billion for licenses to operate “third-generation” mobile networks that enable European users to zap videos and data by phone. The result: Mountains of debt, but a chance to sell phones packed with features James Bond would love.

That hasn’t been the case in the United States.

Wireless companies were the No. 2 sector for complaints to Better Business Bureaus in 2003, trailing only car dealers. They were the second-lowest ranked industry in the University of Michigan’s customer satisfaction index, second only to the hated cable companies.

One reason American consumers are miffed is what Forrester Research analyst Lisa Pierce calls “big holes in rural coverage.” In the Tampa, Fla. area where she lives, her wireless calls start breaking up one mile south of her home. Her husband uses a different carrier; his calls break up one mile north.

Another reason for lower cell phone use in the United States is how service is sold. The largest carriers sell phones by subscription, requiring a credit check and a commitment of at least one year.

“We have tapped out the prime-credit segment in the U.S.,” said Roger Entner, a Yankee Group analyst. “Everyone who wants to have a wireless phone and can pass a credit check has one. Everyone who can pass a credit check and doesn’t have one — after ten years of a continuous barrage (of advertising), they’re not going to cave.”

If the industry wants more users, it will have to change its business model to embrace people with iffy credit who are willing to buy prepaid phones, he said.

Companies are hesitant to do that because it doesn’t help them with Wall Street analysts, who score wireless companies’ stock by the number of subscribers added to their networks, the average revenue per user and the rate customers drop their service, a figure known in the industry as “churn.”

Prepaid customers won’t help average revenue per user or churn, he said, so the largest mobile companies aren’t interested, Entner said.

One way around that is joint ventures with companies such as Virgin Mobile USA Llc. Their customers have a higher churn rate and lower revenue per user, but they still pay, Entner said.

No one in the industry is likely to say this, but the fact is, many companies may not want more customers if those customers won’t be big spenders. They would rather focus on getting existing customers to spend more money by signing up for extra services and sending text messages and photos.

At Verizon Wireless, wireless data services contributed $300 million, or 4.7 percent, to third quarter 2004 revenue, up from 2.3 percent in the same period a year ago. One third of the company’s customers use data services, which add an average of $7 to their monthly bills.

That’s one reason that while the number of Verizon Wireless customers increased 16.9 percent in the most recent quarter, revenue increased 23 percent.

What’s true for Verizon Wireless holds for the rest of the industry.

The average monthly wireless phone bill bottomed out at $39.88 in 1988. Since then, it’s been edging up, hitting $49.49 this year, thanks to increased data use.

That’s why all the major carriers are adding wireless broadband to their existing networks, so customers can get used to sending more information faster — and paying more for the privilege of subscribing to such premium services such as video news clips.