Restoring the Hanford Reach

KENNEWICK – A tiny sticklike plant quivered under the icy gusts scouring the east-facing slope of Rattlesnake Mountain – a puny 6-inch sage looking quite small in the vast surroundings.

But if the feeble plant, dusty colored and not exactly living up to its official name of Wyoming Big Sage Brush, can take root amid the bunch grass, it could help restore the valuable shrub steppe. The land in the Hanford Reach National Monument had been destroyed by several fires, including the massive 2000 Hanford fire, and nearly all native plant species were reduced to blackened nubs.

Several U.S. Fish & Wildlife officials and a planting crew braved snow, winds and cold recently to plant the last of about 1 million tiny sage seedlings and tons of other native plant seed as part of a four-year, $6 million federal restoration project.

“The only thing that’s missing here is the sagebrush shrubs,” said Heidi Newsome, a biologist with the federal agency, raising her voice above the wind.

The Arid Lands Ecology Reserve, the territory upon which the work was done, is mostly free of plants not native to the region and is one of the most highly protected areas of the 195,000-acre Reach. Few footsteps mark the land.

“If we get some sage out here, it will be as close as we can get to pristine,” Newsome said.

When the seedlings mature, Newsome said, she hopes eventually to see insects, rodents, lizards and birds that all depend on sagebrush for food and cover to return.

The burrowing owl and sage grouse are two of the better known animals in decline across the United States, and both depend on mature shrub steppe. It’s hoped that with the restoration, the animals will return.

But bringing the sage back is no easy task, Newsome said.

First, crews had to painstakingly collect gads of sagebrush seed, smaller than poppy seeds, from nearby areas. The seeds then were germinated and the plants raised in a greenhouse.

Only about 17 percent of the seeds actually grow, Newsome said. Finally, after about eight months in the greenhouse, they are ready to be planted. But she said only 30 percent to 50 percent of the plants survive beyond three years.

If they can make it five years then they will most likely pull through, Newsome said. “Anything beyond that is gravy,” she said.

About 163,000 acres burned in the 2000 fire, and all 70,000 acres of the Arid Lands Ecology Reserve was burned. Most sagebrush won’t grow back once it’s burned.

Newsome helped fight the fire and said she was devastated to see so much habitat leveled. She described the columns of flame and black smoke that ripped through the landscape.

“I’ve never seen a fire like that,” she said.

Even without the fire, shrub steppe was in trouble.

“This is a habitat that’s in particular decline across the West, especially in Washington,” Newsome said.

Development, agriculture, grazing and fire are the main reasons for the decline.

About 10.5 million acres of shrub steppe existed before farming and development arrived, according to a state Department of Fish and Wildlife study. But as of the late 1990s, only 4.3 million acres remained, said Rex Crawford, an Olympia-based ecologist for the Department of Natural Resources’ Natural Heritage Program.

Based on his own research, Crawford said he thinks only 2 percent to 3 percent of that remaining land has sagebrush and bunch grass and isn’t choked with nonnative weeds.

And sagebrush only can be replaced with a significant investment of time or effort.

Sagebrush seeds survive only a year in the soil, so once a mature plant is gone there is little chance of reseeding, Newsome said. Still worse, sagebrush is very slow growing and can take many years to reach a mature height.

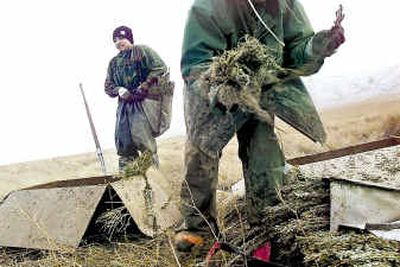

At Rattlesnake Mountain with the planting crew, sagebrush seedlings were unloaded out of cardboard boxes and dipped into a gel solution that would keep moisture near the roots of the plant as it initially struggles to survive. The region gets only about 7 inches of rain a year, so every drop is important. The plants will remain dormant until spring, but when they awaken, the bit of moisture will help get them going, Newsome explained.

Members of the crew loaded the small plants into bags, which they slung over their shoulders.

About eight men strode quickly along the sloping hills in what appeared to be a kind of planting dance. They will plant about 71,000 sagebrush plants this week over about 120 acres, so they had to move quickly.

Gerardo Garcia, 26, of Centralia, quickly thumped the blade of his straight edged shovel with his orange rubber boot twice. He opened the copper-colored earth and nimbly inserted a tiny sage. Then he deftly tamped the soil back into place with three taps of his foot and strode four paces before starting the dance again.

Garcia said he has been planting seedlings of all types across Washington for two years.

“It’s OK,” he said, smiling without slowing his pace. “I like hard work.”

The plants are being placed near roads and firebreaks so they can be defended against future fires.

“We have the ability to protect it,” said Dave Smith, a Fish & Wildlife resources specialist.

Perhaps more dangerous than fire for sagebrush are humans.

Sage get little respect, especially from some people who have lived around it all their lives, Smith said.

“They see it, but they don’t see it,” he said.

Smith said often Fish & Wildlife officials try to educate people about sagebrush, because many view the plant as worthless. The federal agency holds a class and field trip onto the Reach each spring.

“They are the trees of our forest,” Smith said. “We are just trying to jump-start nature a little bit.”

A short drive down a gravel road, Newsome and Smith pointed out some sagebrush planted just two years earlier. They were bushy and just about ankle high.

Newsome, a new mother, said she feels rehabilitating the land has become even more urgent. “For our children and our grandchildren it’s really important to preserve some of these places,” she said.