Jail drug costs soaring

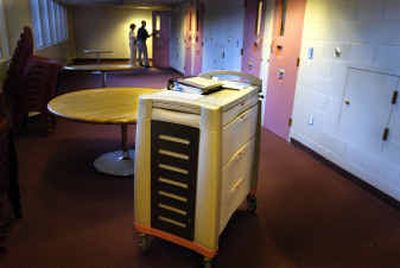

Sheriff Mark Sterk wants to build a pharmacy and hire a pharmacist for the Spokane County Jail to slow the skyrocketing medical costs driven by a growing population of mentally ill inmates.

As social programs for the mentally ill dwindle, those patients are filling the jail and forcing the county to pay for necessary prescriptions. As a result, the county is on pace this year to spend three times the money it budgeted to provide medical care and drugs to inmates, Sterk said.

In 1997, the county spent an average of $8,000 a month for medical care and prescriptions for inmates. Last month alone, it spent a record $80,000.

“We want to do something about it, and I think we can,” Sterk said. “The more global issue is how do we make these people more healthy and maintain them out in the community rather than in jail.”

Along with convincing county commissioners to approve the pharmacy plan, sheriff’s officials are working with Washington State University on a $100,000 to $300,000 grant proposal that would study the benefits of continuing drugs and supervision for mentally ill inmates after they leave jail.

“Without their meds, there is a high propensity for them to reoffend and wind up being incarcerated again,” Jail Commander Dick Collins said. “With the continuing budget crunches that Eastern State Hospital deals with, it just becomes a matter of who has a bed where I can take this individual. Regretfully, a lot of them end up in jail.”

Of the 637 inmates in the jail on Tuesday, Collins estimated that 135 of them were taking prescription drugs to deal with mental illness. But bills for psychotropic drugs are not the only ones the jail must pay.

“The individuals who come to jail are not usually the healthiest anyway. Especially the ones addicted to meth,” Collins said. “Once they are booked into jail, they become my medical bill.”

If an inmate has insurance, the county bills it for medical costs. “But if they don’t, we foot the entire bill,” Collins said.

The jail administers about 25 different drugs to treat everything from heart problems to HIV infections. “It’s not unusual for us to take individuals for kidney dialysis,” he said.

Medical bills also include stays at local hospitals. One inmate, who was charged with domestic violence and sexual assault, ran up a $190,000 bill earlier this year after he spent 2 1/2 months in a hospital. The county also had to pay about $35,000 in overtime to a jailer to stay with the inmate, Collins said.

The county just recently had to pay the medical bills for 50-year-old Charles Robert McNabb, who tried to commit suicide by starving himself. The last three weeks he was incarcerated, McNabb’s failing health caused jailers to spend $1,000 a day to transport him daily to Sacred Heart Medical Center. Before he pleaded guilty to arson, McNabb stayed at the hospital for five days, Collins said.

But the largest increase in cost has come from prescriptions. And the seven most administered and most expensive drugs are those used to treat mental illness, Collins said.

“We get them stabilized while they are in jail,” Collins said. “Then they leave and go off their meds.”

One of the goals of the grant will be to keep contact with the released inmates to make sure they remain on their medication, Sterk said.

“If we are lucky enough to be awarded that grant, I see it as a great tool to diagnose and hopefully come up with recommendations for the mentally ill people who are filling our jail,” he said.

For instance, inmates at the state-run Airway Heights Corrections Center typically get 30 days worth of medication when they are released, Collins said. But inmates released from the county jail get nothing.

What’s more, mentally ill people who had been receiving benefits from the state Department of Social and Health Services get those services cut when they are incarcerated. Once they are released, the inmates must re-apply for those benefits. “It could take as long as 90 days before they start receiving coupons and benefits again,” Collins said.

Sterk said that’s when most of the mentally ill patients come back to jail. “Sometimes they are just so significantly ill that they just don’t have the skills to keep themselves healthy.”

So Sterk has approached county commissioners with the idea of building a pharmacy and hiring a pharmacist. Snohomish County did that and those officials have kept their medical bills down to around $25,000 a month, Sterk said.

“They wanted more information,” he said of the commissioners. “The staff is putting together the final numbers.”

Sterk expects to propose the pharmacy for next year’s budget. He hopes to pay the cost out of savings from the program, Collins said.

Currently, the jail is required to continue dispensing drugs to inmates who had been prescribed psychotropic drugs by their doctors and psychiatrists. Those typically are the newest generation of drugs and are the most expensive, he said.

But a county-hired pharmacist could work with the jail doctor to review prescriptions to determine whether they could substitute a name-brand drug with a generic version for a third of the cost, Collins said. And, the county could join a coalition of care providers who could then purchase drugs in bulk.

Collins said prison officials at Airway Heights pay less than a nickel for one brand of drug while the county currently pays a retail price of $2.50 for the same pill. “If we have our own pharmacist, we can get into that group-rate buying,” he said.

Sterk said the goal from both the pharmacy plan and the grant is to make more beds available in the jail and to reduce costs.

“It’s the taxpayers who pay that bill,” he said. “I think there’s a big potential here to save the taxpayers a lot of money.”