Illumination sensation

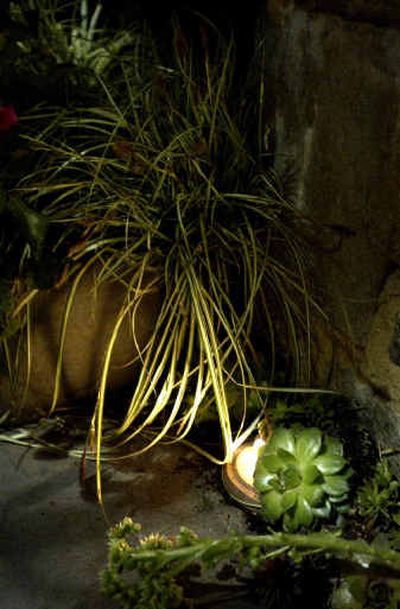

When Glen Blandy looks at a house and garden at night, he sees it as a scene on canvas just waiting for an artist to paint it — with light.

Which isn’t surprising, since this landscape lighting expert started out as a high school art teacher about 30 years ago.

His medium may have changed, but Blandy still sounds like an artist as he talks about negative and positive space, perspective, highlighting, shadowing, and all the other effects that create what he describes as a “dynamic nightscape.”

Many of these were on display at the recent Philadelphia Flower Show, where Blandy worked on the lighting for “Paths to Paradise,” an exhibit by Stoney Bank Nurseries in Glen Mills, Pa., that won best-of-show honors for nursery owner Jack Blandy, who is Glen’s older brother.

Stoney Bank’s display, like many others at the flower show, is a source of ideas for savvy gardeners and homeowners, not only on useful plants and interesting hardscaping, but on how to show them off to best advantage, even after dark.

One exhibit after another at the show illustrates how well-placed lights can accentuate a plant, highlight the texture of a tree’s bark, bring the depths of a pond to life, or make a path seem almost magical.

On a basic level, lighting is important for safety and security, says Glen Blandy, but it can also increase enjoyment of your home and garden.

“Lighting creates an inviting mood,” he says, that can entice you into the garden even if you don’t get home from work until after dark. And its appeal isn’t limited to one season.

“A lot of people think it’s just for the summer, but this is a beautiful idea year-round. Imagine waking up to a snowstorm, or an ice storm, and seeing the lights glistening off limbs or trees — it just can’t be described. It’s one of the most beautiful sights you’d see in your life.

“Even frost or fall leaves or a fine misty rain — there’s so many things that are accentuated by lighting.”

In the Stoney Bank exhibit, he says, the effects include path lighting, uplighting, downlighting, silhouette lighting, and grazing.

Silhouette lighting is achieved by illuminating a wall behind plantings, so that at night the dark outline of a plant is silhouetted against the warmly lit wall. And grazing is the effect you get when a light just grazes the surface of a structure, such as a wall, to accentuate texture.

Then there’s the one-of-a-kind lighting that is a collaboration of artists — metal sculptor Greg Leavitt, who created the arch at the Stoney Bank exhibit’s entrance, and glass blower Will Dexter, who formed the glass flowers that adorn it. Blandy provided the illumination.

A few years ago, he went into the lighting business more or less full time with his own company, Creative Visual Environments in West Chester, Pa. The business wasn’t exactly new; he had operated it part time for years, designing stores and offices and doing visual merchandising.

Anyone can have lights in the garden, Blandy says. His company has installed them at properties ranging from a small courtyard garden in Philadelphia, where 10 to 12 lights, a transformer and installation might cost $2,000 to $2,500, to a large suburban estate, where hundreds of lights and many transformers could cost $70,000.

There are kits for as little as $100 that do-it-yourselfers can buy from places like Home Depot. Quality of fixtures varies with price, of course, from cheaper plastic to more expensive brass and copper, which are likely to last longer.

Whether you hire someone or do it yourself, there’s more to it than sticking a few lights into the garden. “People make the mistake of having a bright post light, thinking they are lighting the walkway,” Blandy says. “But usually that light is at eye level, and it blinds you so that it’s harder to see the path because of the glare.”

More effective are path lights, he says. The traditional mushroom variety, which can be very decorative, throws light down onto a path; but small half-moon lights are more effective for steps, as they throw light across the surface.

Avoid the runway effect. Too often, says Blandy, people put lights evenly along both sides of a path, which makes it look as if they’re waiting for a plane to land. “On a straight path, a couple of lights at the beginning and a couple at the end will do,” he says. “And it’s a lot more interesting and attractive if you stagger the lights.”

Less is more when it comes to lighting the exterior of your house, too. “You go by some homes and they’re lit up like a prison or something,” Blandy says. “You don’t want to light your house evenly across the front, because that flattens it. Highlight specific areas, such as a chimney, and leave some of it dark.”

In the garden, positioning a light in a dark area can illustrate depth. But lights can also bring a garden to life at night. Uplighting, for instance, can pick up the color of a flowering shrub or tree, or even a rose growing in front of a pillar, as it does in the Stoney Bank exhibit. For interesting shadow play, use uplighting or downlighting to create patterns of leaves on large pots or walls.

Check the lighting effects from inside as well as out. And make sure none of your lights are blinding your visitors or shining into your neighbor’s windows. “They shouldn’t hit a viewer’s eyes straight on … so you should check all the angles from which your lighting will be viewed,” Blandy says.

Even glaring porch lights can be a problem. “They should be softened by frosting the glass or using a lower-watt bulb,” he says. “Even if that’s the only light you have, it’s a lot more effective if you can accent an area such as the steps for safety, rather than having it shining (directly) at you.”

Blandy also stresses safety when it comes to installation, such as positioning all wires at least 8 inches below ground where they cross lawns, and making sure all connections are as watertight as possible, because any moisture reaching a wire can cause corrosion, which reduces the power to lights.

Landscape lighting is low-voltage, which uses less electricity, he says. A lot of landscaping uses 12-watt lights; the most powerful he uses is 36 watts. But beware of voltage drop, which can do odd things to your lighting. Voltage lessens the farther the electricity travels through a wire, so don’t overload a transformer with too many lights. Rule of thumb is not to go much over 75 percent of a transformer’s capacity.

“Say a lamp or bulb is designed to burn correctly at 12 volts,” he says. “If it is getting less than 12 volts, the light will have a tendency to start to turn orange, which is great for Halloween but not for everyday functionality.”

Before you hire somebody, Blandy suggests, ask for references and look at photographs of jobs the installers have done, or ask to drive by a landscape they’ve lit. And he has advice for anyone doing landscape lighting:

Take photographs of where your wires run, so you don’t dig into them next time you add a shrub or tree.

Don’t use bulbs that exceed the recommended wattage of a fixture.

And be sure no lights are covered with mulch, to prevent fires.