City routinely dumps sewage into river

The thousands of gallons of concentrated sewage that spewed into the Spokane River on Monday when a tank ruptured and killed a city worker aren’t Spokane’s only sewage pollution problem. Raw sewage combined with wastewater is routinely dumped into the river, state records show.

Illegal discharges can occur during dry weather, but most of the sewage discharges are legal because they happen during big rainstorms when the Spokane Wastewater Treatment Plant is overwhelmed. Upgrades are under way along the river and at the plant that will help reduce the combined sewer overflow problems – but they won’t be complete until 2017.

The river also has a host of other problems, including PCB contamination from industrial discharges east of Upriver Dam, low oxygen levels that threaten fish, dams that have altered river flows, overly warm temperatures and inadequate flows in the summer, sewage discharges from Idaho that exceed Washington state limits, and tons of heavy metals washed downstream from a century of mining in Idaho’s Silver Valley.

American Rivers, a national environmental group, called attention to these problems when it ranked the Spokane River the sixth most endangered river in the country this spring, calling it a “gem” in need of rescuing.

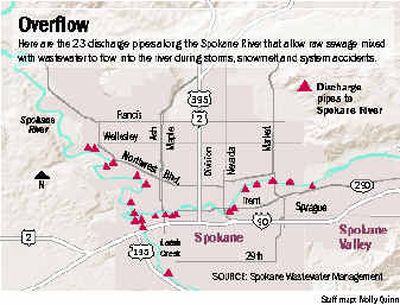

A review of city reports to the Washington Department of Ecology shows that millions of gallons of sewage mixed with storm water in combined sewers in older parts of Spokane are discharged to the river each year at 23 locations. In 2001, 29.3 million gallons went into the river. In 2002, the total was 34 million gallons.

Since the mid-1990s, the city has had an average 450 sewage overflows a year, said Lars Hendron, principal engineer in the city’s wastewater department. “We want to get to 23 or fewer by 2017 – and we have an aggressive plan to get there,” Hendron said.

The combined sewers are a legacy of the past, when Spokane’s original wastewater system carried all sewage to the Spokane River and Latah Creek – where it was dumped untreated. In the late 1950s, the city built a primary treatment plant and interceptor systems to treat the sewage before it went into the river. Many other Northwest cities, including Portland, have similar systems that still discharge some raw sewage into rivers.

Today, only half of Spokane’s old wastewater system has been separated into sanitary and storm water systems. A $50 million upgrade in the 1980s eliminated about 86 percent of the volume of sewage-tainted overflows to the river.

But more than 400 miles of combined sewers, primarily on the city’s south side, are still in service. During big rainstorms and rapid snowmelt, the combined sewers can exceed the system’s capacity, resulting in continued river discharges.

Because of the immense cost of the sewer upgrades, the Washington Department of Ecology has agreed to the 2017 compliance deadline for the river discharges. By then, Spokane must have no more than one overflow for each of its 23 river outlets a year, said Len Bramble, an Ecology permit supervisor.

Some environmentalists say the compliance schedule is too lax.

“The state has given Spokane very generous discharge limits and a very long time to comply,” said Rachael Paschal Osborn, an attorney and water law expert who organized a forum on the Spokane River at Gonzaga Law School last Friday.

The sewage that reaches the river in routine overflows can be far more diluted than the sludge that went into the river Monday from the ruptured tank at the sewage treatment plant. But it can sometimes pose a public health risk – especially when river levels are low. The combined sewer overflows carry human bacteria, viruses, chemicals and oils into the river. In the summer, people using the river for swimming and bathing can be exposed to pathogens in the sewage, state regulators say.

The risk to people “depends on how much water is in the river and how big the storm is. You could see a huge spike in the fecal coliform bacteria. If it’s just a routine event, there’s far less,” said Ken Merrill, an environmental scientist with Ecology.

Officials have said the sewage discharged in Monday’s accident has been diluted and does not pose a threat to the river.

The last time the city was fined for exceeding its sewage discharge limits was in 1999. Ecology fined the city $15,000 for three days of illegal discharges of raw sewage in August of that year when it wasn’t raining, records show.

The discharges occurred at outlet 15, 2.5 miles upstream of the T.J. Meenach Bridge, after a weir – an engineered diversion between the combined and sanitary sewer lines – was blocked. The same weir plugged up in 1998 as well. A Spokane television reporter and an Ecology inspector found the leak before the city noticed it, an Ecology memo says.

Regulators recommended a $15,000 fine because of the risk to human health from untreated sewage during the summer, when people are swimming and camping. They also rapped the city for taking two days to locate the problem outfall and failing to report the spill to Ecology or the regional health district.

Although the precise number of similar incidents is unknown, Ecology had received 13 complaints since 1995 about sewage spilling to the river, agency inspectors said in their summary of the 1999 incident.

City officials appealed the fine, arguing the discharges weren’t intentional. Ecology, in a Dec. 13, 1999, reply to the city, said the discharge “does not have to be intentional for it to be a water quality or permit violation.”

Spokane officials appealed further to the state Pollution Control Hearings Board. In a July 2000 settlement, the city agreed to pay $3,000 in cash to Ecology and contribute $12,000 to the Spokane County Conservation District.

The 1999 incident was the city’s last big fine for unpermitted releases, Hendron said. As part of its settlement with Ecology, the city agreed to post signs at the river outlets with a phone number to report spills. The wastewater department’s Web site displays a flashing icon when a computerized sensor detects a combined sewer overflow to the river.

Spokane also agreed to monitor the river before, during and after the overflows and has compiled data showing coliform bacteria counts along the river, said Ecology’s Mike Hepp.

In 2002, the city built a storage tank for storm runoff at one river outlet near the sewage treatment plant and eliminated one outfall pipe – reducing the total number of outfalls along the river from 24 to 23. City engineers are designing the next storage tank for the confluence of Latah Creek and the Spokane River. That project will eliminate two more outfall pipes, Hendron said.

“The state doesn’t require us to remove the pipes, but we are trying to do that,” he added.

In recent months, records show, there have been additional spills. On Nov. 4, 2003, about 700 gallons of sewage discharged from an overflow pipe at South Riverton and Regal due to a blockage in a diversion pipe. It wasn’t raining or snowing at the time, the incident report says.

Last June and July, another blocked weir immediately downstream of the Monroe Street Dam caused 5,000 gallons of sewage to spill into the river in dry weather. City personnel promised Ecology they’d check the diversion structures with a camera.

Despite these incidents, today’s system is much cleaner than in the past. In 1984, the city completed a large combined sewer separation project that separated 186 miles of sewer in northwest Spokane and eliminated an estimated 86 percent of the annual untreated combined sewer overflow volume discharged to the river.

A plan to further eliminate combined sewer overflows to comply with state regulations was approved in 1994. However, the city delayed implementation because of budget shortfalls and submitted an extended schedule to Ecology. It was approved March 2, 1999, and gives the city until 2017 to meet the state’s combined sewage overflow limit of no more than one event per outfall per year.

The city-owned sewage treatment plant, located on 28 acres in northwest Spokane, works 24 hours a day to treat as much as 44 million gallons of sewage from homes, businesses and nine industrial users, including Inland Northwest Dairies, Hollister-Stier Laboratories and Inland Empire Plating.

Spokane County has purchased 10 million gallons a day of treatment capacity from the city and hopes to build a new sewage treatment plant to serve the city of Spokane Valley, using new technology to make the sewage effluent cleaner.