Survivors keep other D-Day alive

ST. TROPEZ, France — The other D-Day is all but forgotten now on beaches where half-clad vacationers sip Sancerre in the sun. But former Staff Sgt. Richard Fisco, who landed here the hard way, remembers.

“We were supposed to drop miles to the north, but by mistake in the fog we jumped over water off St. Tropez,” Fisco said. “I was screaming to God at the top of my lungs, ‘Get me down on dry land.’ ”

Seventeen men drowned, including his captain, but a gust of mistral wind pushed him to the steps of a villa, clear of the lapping waves. A 14-year-old boy ran up with a bottle of wine and said: “Welcome to France.”

That, Fisco figures, was only one miracle of six miraculous months to follow. Another was Louise, the French nurse he met after battling his way to Nice. They were married 48 years until her death.

In all, 250,000 Allied soldiers stormed France’s Mediterranean shores on Aug. 15, 1944, 70 days after the D-Day landings at Normandy, catching German troops in a pincer so tight that Hitler muttered to aides, “This is the darkest day of my life.”

Operation Dragoon was to have coincided with the June 6 Normandy assault, but there were no landing craft to spare. When it finally happened, paratroopers bore much of the brunt.

For Fisco, who at 84 now lives in Brunswick, Maine, with a French poodle named Francois, not a moment of it has faded from memory.

“My captain drowned, and our sergeant killed himself by accident,” he said, “and that left us with a green sergeant — he had this big walrus mustache — who didn’t know anything.”

Fisco said that despite his pleas, the stand-in commander left his troops in the open, refusing to take shelter in nearby trees without radioed orders to advance. Germans picked off eight men.

In the shadow of Normandy commemorations, scattered ceremonies in the south recall Operation Dragoon’s landings on the beaches between Toulon and Cannes, with paratrooper drops at Le Muy to the north.

Historical footnotes say German resistance was scattered in the south, but that does not explain the thousands of names on graves and monuments — French, American, Australian, British.

Winston Churchill resisted a southern offensive to the last, preferring to focus Allied strength in the north. The Americans prevailed, arguing that a pincer would overwhelm Hitler’s defenses.

Charles de Gaulle also pushed for Operation Dragoon, eager for French troops to play a major part in liberating Toulon and Marseille.

On a recent morning, almost unnoticed by the milling St. Tropez market crowds, old soldiers stood at attention to stirring tapes of the Star-Spangled Banner, God Save the Queen and La Marseillaise.

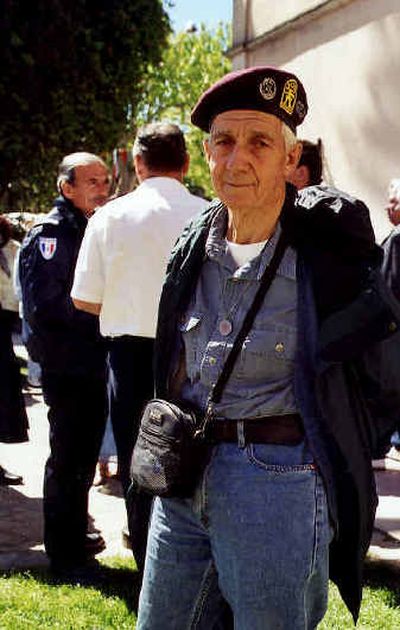

Fisco, in his medal-bedecked purple beret, sat apart under flapping American and British flags. He patted his poodle and quietly wept as Deputy Mayor Jean-Michel Couve saluted the dead.

Then, with Provencal pastis uncorked, the mood changed. One beaming guest was Francois Coppola, that 14-year-old boy who welcomed Fisco to France. He and Fisco found each other after 35 years and are now good friends.

“My parents gave me a wine bottle and told me to find an American,” said Coppola, now 74 and a retired St. Tropez city official. “I found him. He was black with camouflage. I was a kid. But we tracked each other down.”

The two found each other by comparing notes at reunions, Fisco said. “When we figured it out, it all came back to both of us,” he said.

Before landing at St. Tropez. Fisco and his 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion fought at Anzio in Italy, with the war cry “Geronimo” on their uniform patches.

“We held for 72 days,” he said. “That was the closest thing you could imagine to World War I, with tanks and heavy guns. The hills were green with Germans. I went out to scout every day.”

From France, he fought to the German border. On the way, he led an assault in the Battle of the Bulge, where American troops were freezing and dying under Hitler’s last desperate counteroffensive. Wounded in the arm, he refused evacuation back home. Instead, he returned to Nice to find Louise, the nurse.

Because Fisco was still close to the action, officers ordered him back to the front. But a military doctor, after examining Fisco’s mangled arm, changed their minds.

He took Louise home to America. For years, he was a New York City fireman. After a vacation to Nice in 1990, Louise told him he was not going back without a poodle. That’s how the dog joined the family.

At the Rhone American Cemetery north of St. Tropez, in the little city of Draguignan, 861 graves are marked with crosses or Stars of David. The bodies of 1,600 other Americans were repatriated. Headstones among old olive trees and cedars identify brothers, a general, a rare woman soldier-nurse.

Above them all, a stone wall is inscribed, “We who lie here died that future generations might live in peace.”

A large bronze relief map shows the events of Aug. 15 and what happened afterward. Allied units knifed northward, meeting up with Normandy troops coming from the west.

In the visitors book is a long poem in French, written by an American officer about the Allies’ common cause and the sacrifices they made.

“I get shivers every time I see that,” said Pascal Saccoccio, 80, who helps to keep the grounds. He is a French Corsican who fought to retake Marseille.

Saccoccio described himself as despondent over modern-day world politics, afraid that Washington may have unleashed chaos by moving ahead without forging the old alliances that fought evil together.

“We old people have seen these things before,” he said. “But people forget.”

In St. Tropez, Fisco summed up what appeared to be a broad feeling. He was hardly uncritical of France, he said, and he felt President Jacques Chirac went out of his way to slight Americans.

But, he added, Europe and America went deeper than that.

“I have so many French friends,” Fisco said. “You know, people my age, we look at what is happening in Iraq, other places, and we just think it is sad.”