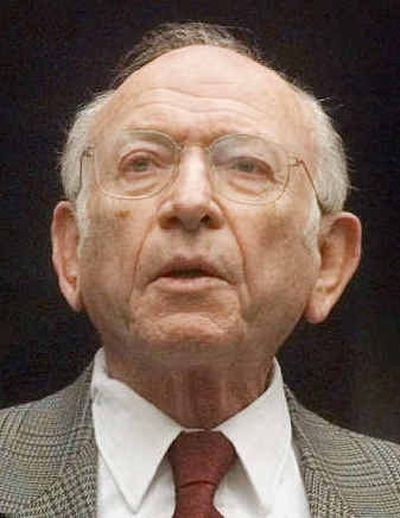

Famed Watergate lawyer Samuel Dash dies at 79

WASHINGTON — Samuel Dash, the chief counsel of the Senate Watergate Committee whose interrogation revealed the secret audiotaping system at the White House which ultimately caused President Richard M. Nixon to resign, died of congestive heart failure May 29 at Washington Hospital Center. He was 79.

Dash asked White House aide Alexander Butterfield, testifying before the committee in July 1973, who else knew about the tapes, which detailed executive office discussions about the Watergate break-in and cover-up; Butterfield replied “The president . . .” President Nixon resigned a year later.

His 53-year legal career touched some of the most important moments in American, and sometimes world, politics. He dramatically resigned in 1998 after four years as the ethics counselor to independent prosecutor Kenneth Starr, charging that Starr became an “aggressive advocate” of impeaching President Bill Clinton, which Dash said exceeded the independent counsel’s mandate, which was a part of the statute that he helped draft.

As the first American allowed to interview the imprisoned Nelson Mandela, Dash wrote a magazine article about him, and mediated discussions that helped free the future president of South Africa. He wrote a book that influenced Supreme Court decisions on electronic surveillance, and he advised governments on investigations into murders in Ireland, Puerto Rico and Chile. But Dash will probably always be associated with the investigation that led to the resignation of President Nixon.

Dash was offered the job on the Watergate committee by Sen. Sam Ervin, who promised him independence and the ability to hire his own staff. He became so well-known as a result of the televised Watergate hearings that he was often mistaken for a senator, and he said he couldn’t buy socks without clerks asking for his autograph. Opponents came to describe him as a prima donna.

It wasn’t until 1981 that Dash dropped by the National Archives to listen to the tapes.

“I didn’t want to go over there just by myself,” Dash told a Washington Post reporter. But when Georgetown University faculty colleagues went to listen to the tapes, he went along and said he was glad he did. “There’s quite a difference between reading the cold print in the transcripts and actually hearing the voices and intonation — the conspiratorial tone of voice.”

It was a point of pride for him that, as a result of Watergate, all accredited law schools require a course in professional responsibility.

During his 1994-98 stint on the Starr commission, he helped persuade Monica Lewinsky to testify. But his relationship with Starr was thorny; Dash’s liberal supporters had been shocked when he agreed to take on the job, and he’d threatened to quit five times before he finally did on Nov. 20, 1998. It was his timing and style as much as the fact of his resignation that was dramatic; it came the day after Starr testified for 12 hours before the House Judiciary Committee, and it came in a stinging two-page document that charged Starr with “abuse of your office” for exceeding his mandate to report to Congress any impeachable offenses he had discovered.

Dash cultivated a reputation for independence and as an advocate for legal ethics throughout his career. In 1951, while he was a teaching fellow at Northwestern University near Chicago, he conducted an undercover investigation into corruption at the Municipal Court of Chicago, which resulted in a seminal report on legal corruption.

Born in Camden, N.J., Dash enlisted in the Army Air Forces in World War II and flew reconnaissance over Italy. After the war, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Temple University, and a 1950 degree from Harvard Law School.

He was a trial attorney in the Justice Department in 1951 and then went to Philadelphia. After several years in private practice, he joined Georgetown Law School in 1965 as a professor and as director of its Institute for Criminal Law and Procedures. He taught criminal law for nearly 40 years, and last year was voted best law professor by Georgetown Law students.

Survivors include his wife Sara and two daughters.