This Memorial Day, new reasons to pause

From the beginning, Memorial Day was about the many recognizing the sacrifices of the few.

Before it became the unofficial start of summer, or of camping season, or a weekend for cars to drive very fast around an oval track in Indianapolis, it was about the community recognizing the individuals lost in war.

Those other things are still out there, Bill Hiatt said last week. “But I think the holiday portion of it has diminished for us.”

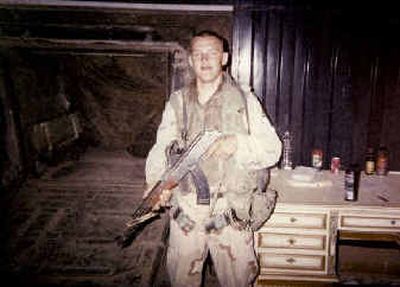

That’s because Bobby Benson, husband of Hiatt’s granddaughter Aimee Hiatt Benson, died last November in Iraq. Army Spc. Robert Benson, 20, was in a tank at a Baghdad checkpoint; he became the first Spokane-area resident to die in the Iraq war, and this will be the first Memorial Day the family has marked since then.

Since that time, two other Inland Northwest residents, Army Sgt. Curt Jordan Jr., 25, and Army Sgt. Jeffrey Shaver, 27, have died in Iraq – Jordan of noncombat-related injuries and Shaver when an explosive device blew up his vehicle.

They are three names among more than 800 casualties of the war in Iraq. As a Memorial Day tribute to those men and women, and their families across the United States, The Spokesman-Review is publishing their names, and their pictures if available, today starting on Page A5.

It’s not a statement for or against the war in Iraq. It’s an acknowledgment of a community’s duty to remember that every war has costs and recognize that those service members and their families bear the greatest costs.

That’s how Memorial Day started, almost 150 years ago. During and after the Civil War, communities across the nation had cemeteries full of new graves of soldiers. Some were well-known native sons; others simply had died on nearby battlefields – in some cases wearing an enemy uniform.

Their grave sites deserved tending at least once a year to honor their sacrifice, townspeople decided, whether the soldiers were related to half the town or complete strangers.

Towns as far apart as Waterloo, N.Y., and Columbus, Ga., claim credit for coming up with the idea first, but the losses from that war were so heavy and the sense of duty so universal that the practice may have been a case of spontaneous generation. In a few years, it had been sanctioned by veterans groups, encouraged by presidents and, most important, embraced by communities.

During World War I, the nation had a new level of sacrifice marked, as John McRae wrote, by “crosses, row on row.” McRae, a Canadian army medic who never got used to the suffering in war, wrote the poem “In Flanders Field” at the graveside of a friend near a battlefield in Belgium. He crumpled up the paper and tossed it away, according to the historians at Arlington National Cemetery, but a friend retrieved it and later sent it to a magazine that published it in 1915. Three years later, McRae was dead of pneumonia; his poem became an anthem to the sacrifice of every war and poppies became a symbol of that remembrance.

By the end of the “War to End All Wars,” Memorial Day became a time to mark the sacrifice of all conflicts, with flowers and flags at gravesites, speeches and parades. In Spokane, local military units held parades at their bases and veterans marched through downtown. Even after World War II started, neither the fevered pace of war production nor the training of thousands of new troops at nearby bases would prompt the community to cancel several days of parades.

It was on Memorial Day in 1943 that Spokane unveiled its first tribute to the community’s dead of World War II. The Cenotaph, as it was called, was erected near the statue of Abraham Lincoln at Main and Monroe; the names of local casualties were added to the monument throughout the war. The monument was made of wood and became so warped that by 1952 it was replaced with a stone marker for Inland Empire casualties of all wars. It also was moved to the Coliseum, which, like its successor the Arena, carried “Veterans Memorial” in its formal name.

Postwar America was fond of dedicating its arenas and stadiums to the memory of fallen veterans, even as it was parsimonious in its praise of surviving veterans of the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Memorial Day also seems to have lost some of its luster in those decades. It became a second-tier holiday – one marked on the nearest Monday, rather than on May 30 each year – to create a three-day weekend for workers. Flags still adorn graves, but they also decorate ads for stores hoping to capture the attention of shoppers with an extra day to purchase clothes or lawn furniture or swim toys for the approaching summer.

Summer in America doesn’t start so much on the equinox as it does on Memorial Day weekend. There’s a fashion convention that says it is now permissible to wear white, a culinary tradition that says it’s time to fire up the barbecue. It is a time to get away. Campgrounds fill up, even in poor weather. Economists analyze the price of gasoline, which invariably goes up, and project the amount of airline travel for the coming months.

All of this is expected, even in a nation at war. Hiatt, a Korean War-era veteran of the Navy who has been active in military affairs in Spokane for decades, said he wouldn’t expect it to change. Memorial Day remains a holiday, he said, and each family handles its remembrances in different ways in different years. There’s no single right way.

“I think it should be an individual situation,” he said. Even as his family faces its first Memorial Day without Bobby Benson, “you can’t ignore all of the other people who have gone through this same thing.”

Each of the names in today’s newspaper represents a loss, not just to family and friends, but to the communities listed as their hometowns. Curt Jordan, a father of two with a knack for fixing old cars, won’t help another neighbor build a house. Jeffrey Shaver, an emergency medical technician turned Army medic, won’t help another patient in distress.

Most of those 800-plus names are strangers to the Inland Northwest. Some readers may wonder why the newspaper would devote the time, paper and ink to so many people who no one here knows. But on the first Memorial Day, communities honored the sacrifice of all of their dead, even the ones who were strangers.