Soldiers’ next stop is war

Mike Kish was sitting on a couch – a nice couch with matching cushions and pillows – trying as hard as he could to appear relaxed and at ease, just another North Idaho homeowner kicking back in the living room.

It wasn’t working.

With even the merest glance at the 33-year-old Bonners Ferry native, electricity comes to mind. Kish’s hair resembles a short, bristly field of copper wire. Leaning into the couch in the Hayden home, arm thrown out across the back, he looks wiry and wired. He is curious, friendly, engaging, but even as he sits perfectly still, there is the impression his legs are twitching.

In a couple of weeks, he will be in Kuwait, then Iraq, as first sergeant in Delta Company of the Idaho National Guard’s 116th Brigade Combat Team.

Like many of the 4,300 soldiers in the 116th – including a battalion of about 400 combat engineers based throughout North Idaho – Kish is on leave. It’s the first time the citizen-soldiers – mechanics and police and teachers and bank managers – have been home since going to Texas and Louisiana for intensive combat training in early summer.

Like other soldiers, Kish finds there are some nights when it’s more comfortable to sleep on the floor. Finds he drives too fast, follows too close. Finds that a two-and-a-half-week leave isn’t nearly long enough to unwind the taut band of alertness and tension that’s been twisting tighter since early July.

Especially since the next twist will carry him onto an airplane to go spend a year around the northern Iraqi city of Kirkuk.

“It’s like I don’t want to get comfortable when I am just going to be uncomfortable again,” Kish said.

“It’s strange. It’s taking me awhile to get adjusted to being back home,” Kish said. “I drive in the pickup and I go too fast. I look at civilians and I feel separated.”

One family, two worlds

The soldiers in the 116th have been separated from their civilian worlds for months, living “behind the wire” at Fort Bliss in Texas and Fort Polk in Louisiana, in round-the-clock training that presumed they were already in Iraq. They strapped on body armor and helmets and guns just to leave the tent. They patrolled, they pulled gate duty and convoy escort, they reacted to simulated mortar and sniper attacks and roadside bombs and ambushes.

“We were living in totally different worlds when he was at Fort Bliss,” his wife, Michelle, said. “My world was carpools and diapers and groceries. His was car bombs and mortars and Arabs.

“It feels kind of strange having him home,” Michelle, 28, said. She and 7-year-old Douglas and 1-year-old David had settled into their own routine.

Plus, she closed the deal on their new house in Hayden. The family had been in the process of moving from Post Falls when Kish was deployed to Fort Bliss in July. He wasn’t sure of his own address, he joked, until he came home on leave. She wasn’t sure he’d like her paint choices, she joked, or the cabinets.

“Whenever he’s gone, I cut my hair and paint things. The other wives do it, too. We talk about it,” Michelle said.

“My friends say I’m too independent,” Michelle said. “It’s one of those things that just happens – you learn to do for yourself.”

Kish has been in the Guard full time for about 11 years as a recruiter. It’s a pretty stable job, but the years since the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks have been tough as the Pentagon digs into Reserve and Guard units for bodies. His company was deployed on active duty for most of 2003 to provide security at Mountain Home Air Force Base southeast of Boise, and now there’s the tour in Iraq.

Deployments bring a level of sacrifice and loss that friends don’t seem to understand, the Kishes said.

“Last deployment we had a child. This deployment we bought a house,” Michelle said, noting Kish was gone on duty each time. “Out of the last three years, he’s been home about six months. I have friends who have husbands who are accountants or postal workers – good friends – but when it comes down to the nitty-gritty, their day-to-day reality is so different.”

It’s like being a single mom, Kish said.

Worse, Michelle said, “because he’s still a part of who we are.” It’s not like an ex-husband or ex-boyfriend she can just cut out of her life, she said.

“When they say absence makes the heart grow fonder? There’s some truth to that,” Michelle said. “He writes really nice letters – and you come to like the man in the letters. Then he comes home and you get the first sergeant.”

She and Kish, sitting side-by-side on the couch as year-old David played at their feet, laughed together. They know the deal.

They both know the first sergeant will get grumpy as the leave runs out. “As time winds closer, my anxiety level will raise. I want to get there and get to Iraq and get to work,” Kish said.

Not in your box of Army men

There was a moment at Fort Bliss in the baking heat of August when a hidden side of the military shimmered into view like some wonderful mirage. Two visiting journalists and their keepers were at the supply trailer trying to get a couple of Camelback water bags. There was a lot of shrugging and smiling and head-scratching, but no Camelbacks for journalists. Highly irregular. Most unusual. Try later.

A large young soldier walking nearby spun his heel in the gravel and leaned close to the visitors.

“Hey,” he said in a low voice. “If you need a Camelback, come by my Humvee tonight. I’ve got five.”

The soldier is Spc. Aaron Bray, 21, of Coeur d’Alene. He is Kish’s driver. And since joining the Guard he has learned things they don’t teach you in basic training: such as how to acquire things that come in handy.

“There is definitely an underground to the supply world,” Bray said. “It’s like watching old MASH episodes.

“When you are a kid and you play with your army men, they are all infantry,” Bray said. “There are no cooks, no supply clerks. They’ve all got rucksacks and rifles and they shoot people with their guns.”

But then you join up, he said, and find there are layers upon layers of Army men and layers upon layers of rules and regulations.

“I don’t mean this in the sense that you are conniving, because you do try to make sure you play by the rules,” Bray said. “But you want to make sure you end up with what you need.

“It’s like life, isn’t it?”

Bray, at 6-foot-4, 230 pounds, was looming over a small table at a downtown Coeur d’Alene coffee shop last week on a brilliant sunny afternoon. He and his wife, Amber, talked about how their lives have changed dramatically in a short time.

Bray went to Christian schools around Coeur d’Alene but then came teenage angst. “I dropped out of school, got my GED” and was bored stiff, he said.

Then “I got in a fight with my mom – something small and dumb – and she said ‘Why don’t you go join the Army?’ So I just drove right over and signed up. Drove back and told her.”

He was no sooner out of training than he was deployed to Mountain Home for a year. He was no sooner on deployment than his grandfather, Fred Kaphingst, died – “He and I were like close friends,” Bray said. During all this, a family friend, 23-year-old Jay Blessing of Tacoma, a sergeant in the 75th Ranger Battalion from Fort Lewis, was killed in Afghanistan on Nov. 14, 2003, by a roadside bomb.

But in the loss came a few other things. Bray said he was honored to be a soldier in uniform and chosen to accept a presentation of medals the military belatedly bestowed upon his grandfather, a veteran of World War II and Korea. And by May, the Army officially bowed to the sentiment of the 75th Rangers and renamed the base in Asadabad, Afghanistan, as Camp Blessing, complete with 21-gun salute.

And last November, with the Mountain Home deployment ending and rumors of Iraq beginning, Bray and Amber moved up their wedding date.

“I think my idea when I joined was ‘Soldiers. Cool.’ ” Bray said. “It means something a lot different to me now. It’s pride and honor.” And it’s a clearer future, he said, his goal to become “21 Bravo.” That is, a combat engineer.

“I think we’ve both changed,” Amber said. “He’s a lot more patient. He’s had to go through a lot.”

And after deciding to push up her wedding by half a year and pull it off on a shoestring of $1,500, she doesn’t sweat the small stuff, she said.

They were watching a newlywed show on TV the other night, and it was filled with bickering couples. Bray and Amber looked at each other, they said. “It was all so minor,” she said.

Return of the warrior

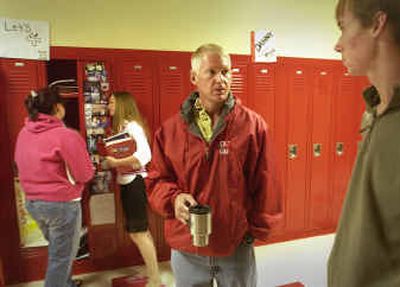

Kevin Kincheloe, soon to be 48, looked nearly a decade younger as he roamed the halls at Kootenai High School near Harrison in early November. He was gripping a travel mug full of good coffee, wearing blue jeans and a tropical shirt and a bright red windbreaker that bore the logo of the school sports teams: Warriors. He’s a sergeant first class in Delta Company, but before he was called to active duty in the spring Kincheloe was a teacher, counselor and coach at the high school here.

Students, teachers, office staff beamed in surprise as he drifted around the building. “Kinch!” they’d exclaim. He traded handshakes and hugs and playful shoulder punches and asked about the fortunes of the football team, academic progress and home life. The hallways of Kootenai High are the information superhighway for news in the tight community around Harrison, and Kincheloe hungered to catch up.

“It was hard on the kids when he left,” special education teacher Kathy Boswell said.

“He’s been here 18, 19, 20 years,” librarian Carol Daniels said. “Plus he’s not shy. He’s really involved with stuff.”

But there was always his warrior side to Kincheloe, the women said.

“He’s always wanted to be a GI Joe. He missed Vietnam. It’s kind of like he thinks he missed his time,” she said.

Boswell added “I think he has the values of the generation before – a feeling that you should serve your country.”

It was 1961 or ‘62 when a little Kevin Kincheloe saw his future. He was watching television, he remembers, and it was a Saturday morning when something extraordinary happened.

“The cartoons were pre-empted by Walter Cronkite saying we were going to war,” Kincheloe said.

The war was in Vietnam, and it lingered and lingered as Kincheloe grew into his teens.

“I always expected I would go to war,” he said.

But the long stalemate in Southeast Asia ended just before Kincheloe became a soldier. He joined the Marines in 1975 when there was no war to fight. He left the Marines in the late ‘70s and made a career teaching, coaching and counseling at the little high school near Harrison. He wed, raised three daughters, gardened, hunted and hurled himself into marathons and other physical tests.

As the years passed, “A friend of mine in Colorado Springs would call me up after Granada, after Panama, after Desert Storm,” Kincheloe said. ” ‘So,’ he’d say, ‘we missed another one.’ “

Now Kinch’s war is here.

He could have missed this one, too. His enlistment in the Guard was up in October, but the military’s stop-loss policy roped him in for another two years. Kincheloe makes note of the extended deployment, but doesn’t complain.

“I’d like to say it’s patriotism, but I’m not so sure,” he said, sitting in a pool of sunshine at a picnic table behind the high school. “This war, it’s hard to justify the expenditure of human and monetary resources.

“We have our own war on terror right here. It’s our dropout rates and underinsured people, and people with no insurance, and teen pregnancy,” he said. “I think juvenile justice would like some of the money going to Iraq.”

At Fort Bliss he was reading author Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried,” a powerful story of being a soldier in Vietnam.

Kincheloe was struck, he said, by a passage where the narrator rushed toward Canada, but then turned back still thinking the war was wrong but also wanting to face the people in his town.

“I wrote that phrase down in my journal – ‘simple-minded patriotism,’ ” Kincheloe said. “It boils down to simple-minded patriotism: You get the spin off the television and the war is so far away.”

His motivation, he said, is “A sense of responsibility” to ensure his platoon, his guys, are trained as best as he can train them “and hopefully bring everybody back alive.” For all of them, the war will not be far away.

“I’m not sure I could have gotten out and then watched everybody go. I think it would have been hard. It’s my platoon,” he said.

Death, do not follow me

“The deployment at Mountain Home was a pain – because he was gone – but I was not worried about his safety,” Michelle Kish said. “This is a whole different ball of wax.”

“Maybe we will be a fortunate company and take no casualties,” Kish said. “There are units in Iraq who have come out like that. But that first casualty is the one I worry about. That’s when the reality will hit. Michelle doesn’t like to talk about it, but I have to come to grips with it.”

Michelle Kish and Amber Bray have had to grow a shell of stoicism.

“If I thought about it, I’d go nuts,” Amber said.

Daniels, the Kootenai High librarian, gossiped and chatted animatedly with Kincheloe. But she became somber when he left the room. Her husband of three decades died this summer, but she thinks there was a piece of him that never came back from Vietnam.

Halfway through his tour, “His letters changed,” she said. “It changed his life. He didn’t talk, not for 20 years.”

Only in the last years of his life, Daniels said, did her husband begin to tell her at least one story about a man sitting right next to him blown into pieces while he was unscathed.

“He said terrible things happened to people. I think he died from the war, just from the experience,” she said.

One of the terrible things is that survival can be so random. “A lot of it amounts to luck,” Kish said. “They used to say in training that if we saw a suspicious pile of garbage, stop and check it out because it could be an IED (improvised explosive device). But then you hear there is so much trash – piles of garbage everywhere, burning cars – that you just get used to it.

“You hear (veterans) talk about the things that are happening over there and it changes your view of mortality. You know you’re not immortal,” Kish said. “For a family it’s a year of inconvenience. For a soldier it’s a year of life change.”

So for North Idaho part-time soldiers, so close to Canada, why go?

Sure there is the mission, the global war on terror, winning the hearts and minds. All this is valid, but there is something deeper and truer.

“You ask any soldier: It’s a test of manhood,” Kincheloe said.