Paper work

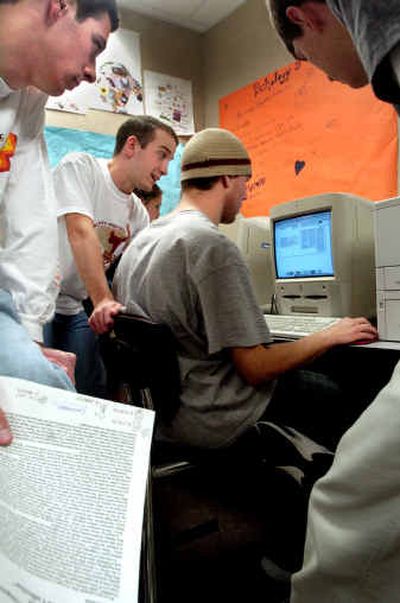

Something is going on in Eric Woodard’s 1:40 p.m. class at Lewis and Clark High School. His 20 students are gathered in groups, discussing, debating and acting as if school were more social experience, less learning experience.

“You come in, and it looks like we’re not doing anything,” Woodard said. “It’s hard for me, because as a teacher, other teachers come see that, and it looks like they’re screwing around.”

The outsiders are getting an inside look at students hard at work at high school newspapering, pre-journalism 101 where organized chaos – with the emphasis on chaos – is the standard. Yet, every four weeks the students’ actions are validated when the Lewis and Clark Journal hit the hallways and the classrooms.

It’s a chance to give young journalists the opportunity to experience the excitement and angst associated with writing, editing and accountability. There is no hiding after a less-than-flattering review of a play or an opinion piece ridiculing a school’s lunch policy.

“Our paper is for students, and I really like how our paper doesn’t fall into that hardly-more-than-just a newsletter category,” said Journal news editor Hillary Eaton. “I know somebody who is on another journal staff. She was telling me they are not allowed to give an opinion.”

All work on newspapers is done during class hours. Woodard’s class, an elective, meets the last period every day. Many seniors take the class instead of a free period. When publication date nears, they give up their Saturdays. Teachers also make sacrifices for the paper. In the Spokane district, budget cuts two years ago eliminated the stipend they got for putting in extra time to help student journalists.

At North Central and Rogers, the newspapers have been redefined to fit teachers’ class loads and budget constraints.

This school year, the Rogers Record – which has been around as far back as the 1930s – has been folded into Maureen Murphy’s creative writing class. Instead of 10 editions a year, the students publish quarterly. Murphy, English department chairperson, said the paper is in a holding pattern until second-year-teacher Tracy Telgen takes over the newspaper next school year.

“I’m not going to let this die, It would be harder to resurrect the paper from the dead than the nearly-dead,” said Murphy, a teacher at Rogers for 13 years. “There is always interest. You always get kids who are fascinated with newspapers.”

While some high schools, such as Shadle Park, don’t have student newspapers, there still are many valued newspapers at county schools. The Mead Xpress in the Mead School District prides itself on its attractive design. Much like the LC Journal, The Mercury at University High focuses on writing more than graphics.

Regardless of the emphasis, the methods of getting to the finished products are the same. Reporters initially turn procrastination into an art form. Stress levels build as deadlines close in. Panic takes over as due dates shrink into hours. The paper gets out.

“There’s definitely a lot of stress, but it’s very rewarding, so it’s worth it,” said Heather Grover, a junior at U-Hi and co-editor of The Mercury. “This is like a job, but you have other classes to focus on as well. It’s more of a work environment in here.”

It also doesn’t take an investigative reporter to uncover information that Paul Jensen’s newspaper class is a popular elective. This trimester, 32 students pile into Jensen’s classroom for 90 minutes each day. During the first two weeks of The Mercury’s one-month cycle, students collect information and write rough drafts. The third week is spent rewriting – and haggling with editors. Advisers make the final read. The last week is set aside for layout.

“It’s not an English-based class, but I’ve learned more about writing in this class than any other class since freshman year,” said Mead senior Bethany Robinson, managing editor of the Xpress.

The work flow is similar at other papers. Students also are required to learn a variety of jobs, from taking photos to selling ads, which helps defray expenses. For the most part, advisers also encourage students to come up with their own story ideas. Verification by expert sources also is required.

“They think it’s going to be really easy at first. … ‘I just want to write about this,’ ” said Jensen, whose first newspaper class seven years ago had 10 students. “Then they learn they have to figure out how I’m going to start it? How am I going to grab people with the subject? It has to interest a wide variety of people.”

Dale Kaiser’s students on the Mead Xpress have been known to take a less conventional approach to capturing an audience. Each edition, they choose a theme for their center section. Last year, topics ranged from Thanksgiving to springs (water, trampolines, mattresses, you name it.) Student Kelly Bunkers went as far as crafting a piece on the wildly popular Nalgene polycarbonate water bottles, although it wasn’t played in the center section.

“This year we want to do more with teen issues,” said Bunkers, section and distribution editor.

One of first topics Kaiser’s staff of 12 focused on was premarital sex, with angles on religion, the media and friends.

“No one barked at us, we didn’t hear a peep,” Kaiser said about that issue.

Mead’s upcoming issue will focus on living in Spokane versus living on the West Side. Students will take sides and let the opinions flow.

“When you hear something from your peers, a lot of time it carries more weight than if you hear something from your parents or teachers,” Bunkers said. “When you’re hearing it from your peers’ perspective, you’re thinking, ‘Oh, I’m not the only person thinking such and such.’ “