Too much with too little

It’s a refrain voters hear every election season: Schools need more money.

Candidates promise more. Property owners get tapped for levies. And tax support rises steadily. The total per-student spending in the Spokane School District went up 25 percent in the last decade, when adjusted for inflation.

Still, educators say they’re strapped, burdened by new federal demands for testing and reform. In Idaho, education spending has been flat for the past few years and the possible rollback of a 1 percent sales tax could mean deep cuts. In Washington state, voters are being asked to pay more in sales tax to help fund education improvements.

“We’re in the middle of a huge transition where we’re being asked to get results that have never been attempted in organized society previously,” said Spokane Public Schools Superintendent Brian Benzel.

Even tax opponents agree that schools could use more money – their only complaint is where the bite would fall.

“Our schools are being asked to do too much right now. Teachers are nurses, therapists and in some cases substitute parents,” said Jamie Daniels, a League of Freedom Voters campaign director who opposes more taxes for education. “We’re not saying the schools don’t need more money.”

More money, higher expectations

The numbers don’t lie, but they may not tell the whole story either.

In terms of overall public school funding, Washington students received ever-increasing funding in the past 10 years. But supporters of the sales-tax initiative, I-884, say statewide funding has not kept pace with inflation. Between 1993 and 2001, per-student funding dipped by $535.

On top of that, reforms, mandates and increased duties have made teaching more expensive, say educators. The No Child Left Behind Act and special education requirements are often described as unfunded mandates that challenge educators to balance demands with tight funds.

Spokane County’s largest school district, Spokane Public Schools, has increased its per-student funding from 1993-1994 to 2002-2003 by 25 percent when factoring in Consumer Price Index inflation. That includes state, federal, levy and private donations.

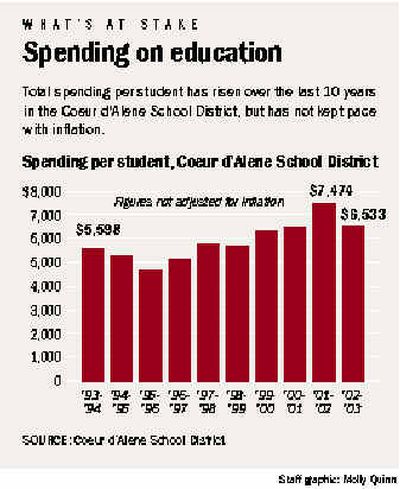

The Coeur d’Alene School District increased its funding for the same period, but when adjusted for inflation, the funding actually went down 6 percent.

“That does not surprise me in the least,” said Jerry Keane, vice president of the Idaho School Superintendent Association and Post Falls administrator.

Heavy student growth and flat funding is wearing the system thin.

“We’re about at the end of our ropes,” Keane said.

In Washington state, the campaign to raise education funds $1 billion annually with a 1 percent sales tax increase has chosen to keep the discussion on money fairly simple. They hammer the point that more money is needed, said Natalie Reber, spokeswoman for the League of Education Voters.

“We don’t break the numbers down. People typically don’t need that much detail,” Reber said. “They just know it’s not enough.”

‘A critical point’

But is that enough information to possess before going in a voter’s booth?

Public education funding is a complex mix of state, federal and local tax, confusing even to those who don’t navigate the multibillion-dollar system on a daily basis. That could be changing, as the discussion heats up on fine-tuning Washington’s education funding model.

The state’s superintendent of public instruction has asked for several hundred thousand dollars to conduct a study on the state education funding system. A House appropriations finance work group has already launched their own study of how the current system works to show what changes are needed.

Last month, a coalition of 11 school districts filed a lawsuit against the state for not providing enough money to meet special education requirements.

Barbara Mertens, assistant executive director for the Washington Association of School Administrators, said her group too has begun a study of the system to hurry the process along.

“We’re reaching a critical point,” Mertens said.

So who does pay for public school education, and how is that done?

In Washington, the state provides revenues based on formulas that calculate full-time student population, mixture of teacher experience and special needs populations like special education.

In Washington in 2002-2003, the state provided $5.1 billion dollars for education, covering 70 percent of costs. The federal government gave $1.1 billion for 10 percent. Local taxes in the form of levies, made for 16 percent, and the remaining 4.7 percent came from a variety of smaller sources, usually private donations from parent groups and others.

From 1995 to 2002, the percentage of state funding in the total budget has gone down from 76 percent to 70 percent.

Federal funding levels have increased 48 percent in three years from $401 million in 2001-2002 to $594 million in 2004-2005. A large part of that increase has been due to rising special education funding. Since 1993, the percent of federal funding in districts has taken a high percentage of all revenue, from six percent in 1992-1993 to nearly 10 percent in 2002-2003.

Idaho’s also seen increases in federal funds, which now account for 7 percent of total expenditures.

‘Money isn’t always the answer’

Federal law requires through No Child Left Behind that all students must read, write and do math at required standards by 2014.

“That’s a huge, ambitious and wonderful goal,” Benzel said. “No business would undertake that goal without extra capital.”

There’s also a new nutrition state standard districts must meet. And there’s new training that must be done for anti-harassment policies required by the Legislature. Each new state mandate piles more duties upon administrations and principals.

“Money isn’t always the answer because of all the strings and conditions attached,” said Cindy Omlin, executive director of Northwest Professional Educators, an association of 350 educators. Her group tends to attract people who have political issues with the state’s teachers union.

Speaking from her experience, there are too many demands on teachers.

“In my view, teachers are breaking their backs and hearts for kids. They are doing the best they can. They need all the support they can get,” Omlin said.

That support could come in the form of parental support and stripping away unnecessary requirements, Omlin said.

Omlin remembers sitting in a staff room during the mid-1990s when she was still in the schools and a teacher broke down crying. The teacher had just learned about a new reading grant, which meant more money, but much more time and effort to document all the supporting information required by the grant.

“I saw a lot of money diverted from student needs and into projects and activities that bloated the budget, but didn’t specifically help kids,” Omlin said.