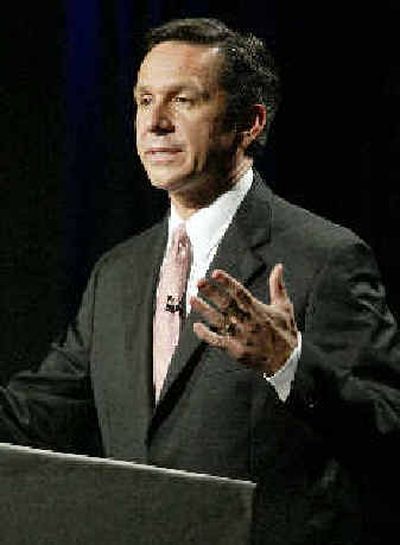

Dealmaker Rossi is all business

Editor’s note: This is the second of two profiles of Washington’s gubernatorial candidates. Democrat Christine Gregoire was profiled Wednesday.

OLYMPIA – If there’s one thing he’s good at, Dino Rossi likes to say, it’s bringing people together.

His paycheck, after all, depends on it. Rossi sells commercial real estate. If he can’t get a buyer and seller to agree, he doesn’t get paid.

A self-made millionaire, Rossi, 45, is apparently very good at getting to yes.

Seven years ago, he turned that skill to politics, becoming a rising Republican star in the state Senate.

Now, after a year of long days and long drives, the senator from Sammamish is hoping to close the sale of his life. He wants to be the next governor of Washington, a state that hasn’t had a Republican living in the governor’s mansion since 1984.

“I never set off on a course to run for public office, let alone for governor,” he said in an interview this week. “Yet one thing kind of led to another.”

Rossi grew up in the Puget Sound region, one of seven children. His mother was part Tlingit Indian; his father was the son of an Italian immigrant who’d worked the coal mines at Black Diamond, Wash. Both parents had previous unhappy marriages; Rossi was their only child together.

Since his father was a schoolteacher and had summers off, the large family spent a lot of time hiking around Puget Sound. They’d camp, fish, dig razor clams.

It wasn’t all idyllic. Rossi’s mother had a serious drinking problem when he was young. She’d come home drunk and mean or sloppily sentimental.

“It was kind of unnerving when you’re real young. But nobody’s childhood is perfect,” he said. In 1967, when Rossi was 7 years old, she joined Alcoholics Anonymous. He doesn’t drink.

Eager for pocket money, Rossi would scrounge up lost balls from the Ballinger Lakes Golf Course and sell them back to golfers. At age 12, he bought a candle-making kit and sold candles to local beauty shops, gift shops and stores.

By the time he was considering college, he’d decided to be a teacher, like his father. His father talked him out of it, saying that Rossi was a born businessman.

Entering real estate

Rossi went to Shoreline Community College and Seattle University, working nights as a janitor and living in a room above his mother’s beauty parlor.

“He knew all the places you could get 10- or 25-cent hot dogs for dinner,” said Vallery Reed-Cogo, a Spokane nurse and Rossi’s sister-in-law.

After a months-long backpacking trek through Southeast Asia, he went to work as a commercial real estate agent and began buying property. Today, his campaign says, Rossi’s net worth is about $3.6 million.

His political career began in 1992, when Rossi ran for a seat in the Legislature and lost. Four years later he was back, ringing the doorbells on 15,000 homes and getting bitten by four dogs along the way. That time, he won.

Rossi’s salesman charm and negotiating skills landed him on the Senate’s powerful budget committee. Within a few years, he was tapped by Senate Majority Leader Jim West – now Spokane’s mayor – to run the budget committee.

“Dino’s kind of a dig-in-and-get-it-done kind of guy,” West said. “And he doesn’t give up.”

Republicans – with a lot of help from Gov. Gary Locke – were quite pleased with the resulting state budget. Despite a recession and a record $2.6 billion budget shortfall, lawmakers passed a mostly no-new-taxes budget that, Rossi says, still protected people.

“Instead of cutting services for the most vulnerable, I made state government go on a diet,” he told supporters earlier this year.

In many quarters, it was not a popular diet. Teachers and state employees didn’t get cost-of-living increases, nor did schools get money that had been slated to reduce class sizes. The number of low-income children getting state-subsidized medical care went up by only 4,000, rather than the expected 40,000.

“He’s really a nice guy, but his smile and his charm serve to cover up the fact that he’s really rigidly conservative,” said Democratic Sen. Darlene Fairley, who served on the budget committee.

At budget time, she said, Rossi would look out for the developmentally disabled or mentally ill.

“But on the other hand, he feels that if you’re a poor mom with a couple of kids, no matter what’s happened to you, he feels that you should be able to do anything,” she said. “He doesn’t understand what it’s like to have no education, no support system, to be overwhelmed by domestic violence. He thinks anybody should be able to pull themselves up out of poverty.”

A big influence

West and others had been pushing Rossi to run for governor, but he was originally aiming for the congressional seat held by soon-to-retire Jennifer Dunn. She’d given him a heads-up last year, six months before she announced her decision.

What changed Rossi’s mind? A chat with President George Bush, who pointed out that governors have a lot more power than congressmen. Bush also suggested that Rossi get a dog, after Rossi’s daughter, Juliauna, left the president a note during an after-hours White House tour.

“We asked our dad if we could have a dog and he said he would get one for us only if you told him to,” the note read in part.

Rossi got a dog – now named Dubya – and ran for governor.

His campaign has revolved largely around a single issue: making Washington more friendly to business. Growing businesses mean more and better jobs, he says, and the resulting taxes will be good for schools, colleges and the social safety net.

“For 20 years, the same people have been in charge. And where has it gotten us?” Rossi has repeatedly told supporters. “Twenty years of anti-business and anti-job policies have come home to roost.”

He’s vowed to cut government regulations and make Olympia’s state agencies work with business.

Rossi’s backers hope that message will win over voters. After all, Rossi donor and Spokane dentist John Condon said, people’s jobs depend on the business climate.

“And it’s a goddamned mess,” he said. “Things have just slowed to practically a stop for any new industry coming in.”

A poll last week by Atlanta, Ga.-based Strategic Vision showed Rossi trailing Democrat Christine Gregoire, 48 percent to 42 percent, with 10 percent undecided. The margin of error was plus or minus 3 percent.

“We’ve got to keep the companies here and keep them happy somehow,” said Rossi’s campaign organizer in Spokane County, assessor Duane Sommers. “It’s so easy for a business to just pack their bags and move across (the border).”

Running for governor has brought a lot more scrutiny than when Rossi was just one of 49 state senators.

Seattle Times investigations into Rossi’s Seattle business dealings have revealed that Melvin Heide, the head of the first two real estate offices where Rossi worked, went bankrupt, cost investors millions of dollars and eventually went to prison for fraud. Rossi said he was unaware of Heide’s crimes at the time. Rossi also said that none of his clients lost money, that he’s never been sued, and that no one has ever filed a complaint against him.

The Times also discovered that a year into his first term as a senator, Rossi partnered with two lobbyists to buy an apartment building. The lobbyists were David Ducharme – whose clients included an auto auction, tobacco company and utility contractors – and his father, Dick Ducharme. Dick Ducharme, now retired, represented builders, the Northwest Racing Association, beer and wine wholesalers, and farmers in the Yakima Valley.

“He was doing business deals with the lobbyists who were trying to get him to pass legislation,” said Morton Brilliant, a campaign spokesman for Gregoire. “It does raise a lot of ethical and financial questions.”

Rossi spokeswoman Janelle Guthrie said Wednesday that Rossi asked for an “informal opinion” from the legislative ethics board before going ahead with the deal.

“Basically, he was told that as a citizen legislator, he’s expected to have outside business dealings and that this would not be a conflict (of interest),” said Guthrie. Rossi and Dick Ducharme had been friends for years, she said.

The ethics board’s Mike O’Connell on Wednesday said he could find no record of such a ruling, but that oral advice on such issues is fairly common. In general, he said, there’s no conflict of interest unless a lawmakers lobby, sell their votes, or benefit from legislation more than someone else in the same industry.

“If the senator had a business relationship with a lobbyist, that wouldn’t, per se, present an ethical problem,” O’Connell said.

End drawing near

The campaign trail’s been pretty grueling this year, particularly in the governor’s race. Rossi said he’s worked 12 to 14 hours a day for nearly a year. He misses the time with his four kids, ages 3 to 13. As a senator, he had a no-politics rule on weekends. No ribbon-cuttings, no parades – that was family time.

As a gubernatorial candidate, he doesn’t have that freedom. Instead, he’s been making speeches in Chewelah and Republic, riding in a parade in Colville, and attending more than two dozen Republican Lincoln Day dinners.

At every debate, Rossi’s made a point of thanking his wife, Terry.

“Only 16 more days, honey,” he said Sunday.

As people get their ballots and the race heads into the home stretch, Rossi says he’s doing well. The hardest part, he said, is not being home at night with the kids.

Rossi also frequently says that he’d be happy with just a single term in office. He says he’d spend four years doing what needs to be done, rather than fretting about his political future.

“I was happy before I got into politics; I’ll be happy afterward,” he said in an interview Monday. “That’s advice I’d give to anyone running for office. If you come to it with a core set of principles and follow those principles, it’ll be OK. A lot of people spend all their time wringing their hands over how they’ll get re-elected.

“It’s very freeing,” he said.