They’re gambling on getting a good job

ALBANY, N.Y. – Marvin Phillips is spending a lot of time this summer at the Akwesasne Mohawk Casino, taking in some poker, roulette and live music. Not for pleasure – for college credit.

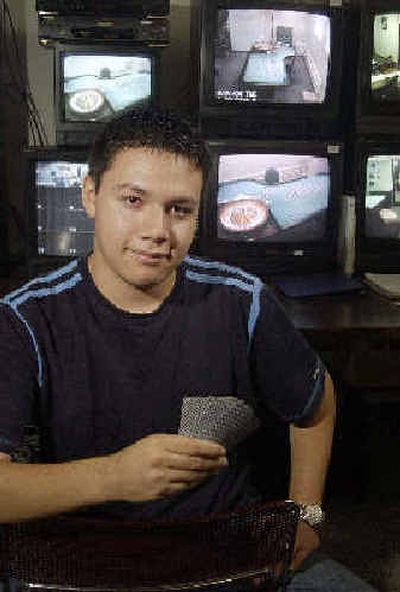

The 21-year-old from the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation will enter his senior year at Morrisville State College in September as part of a growing movement: College educated blackjack dealers, casino security experts, restaurant and entertainment operators and gaming managers.

As states – mostly through Indian tribes – turn to casinos for gambling revenues, public colleges nationwide are increasingly offering courses and majors on casinos and gambling.

Phillips, a member of the Mohawk tribe, started as an information technology major but decided after a year to take gaming courses. He’ll graduate with degrees in both.

“I did this for the most part because of the unique nature of the gaming industry and because there was a casino in my hometown,” he said. “This provides for a challenging work environment that appeals to me.”

Over the past five years, gaming courses and majors have cropped up at colleges including San Diego State University, Michigan State University, Tulane University’s University College in New Orleans, and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. They join the pioneering University of Nevada at Las Vegas and Reno, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

In New York’s Catskill Mountains, Sullivan County Community College added a casino concentration in its club management degree. There are several proposed Indian casinos in the former Borscht Belt of upstate New York, though none has gotten final regulatory approval.

Courses at such schools include the study of gambling laws, operating on sovereign Indian land, and biometrics and “facial recognition” for casino security. Some students learn to be pit bosses, dealers and slot machine repairers.

Class laboratories take on new definitions in these courses that include green felt poker tables and red-and-black roulette wheels. Casino nights – using play money – are held on and off campus, often for charity. Field trips to Las Vegas, Atlantic City and the countless Indian-owned casinos in between are part of the course load.

“I spent 25 years in the business and I always wanted to bring education to the gaming industry,” said Peter LaMacchia, director of the six-year-old casino studies at the State University of New York’s Morrisville State College. “When I started, the business was about who you know, rather than what you knew.”

Morrisville is considering expanding casino-related studies, including a possible four-year degree in the entertainment and gaming electronics.

Not everyone wants to let this trend ride.

“It’s disgusting,” said state Sen. Frank Padavan, a New York City Republican and vocal gambling opponent. “I think it’s inappropriate for the state to become a vehicle by which people are in increasing numbers addicted … To have that policy reinforced through a curriculum in a public university is reprehensible.”

The effort sometimes faces religious opposition and Mississippi prohibits casino courses in public colleges, said Richard Marksbury, dean of Tulane University’s University College, which offers an associate’s degree in casino studies.

“I think anyone who is doing it right now is in a pioneering effort and, anytime you’re in a pioneering effort, respect isn’t the first thing you’re going to get,” Marksbury said.

The National Council on Problem Gambling notes that campus gambling isn’t new: 4.5 million of the nation’s 15.3 million college students will gamble on sports this year, it calculates.

At San Diego State, where the casino industry was screaming for help, a professional certificate in gaming was offered this past spring to serve employers and boost college revenues.

The first course – which costs $240 – had 35 students this spring. The second course also had 35, with a waiting list of 40, said William Byxbee, dean of the college of extended studies at San Diego State.

San Diego County is home to 16 Indian-owned casinos that attract 40,000 players daily and employ 12,000 people. A casino recently announced plans to triple in size and add 4,000 employees.

“They are lined up to hire people,” Byxbee said.