Battles linger at home for troops injured in Iraq

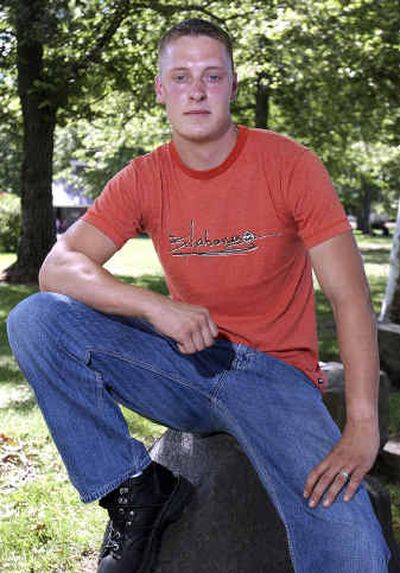

Lance Cpl. Ian Anderson of Spokane was a gung-ho Marine who was shot five times while serving his country in Iraq.

Now he is an embittered 23-year-old coping with his wounds, angry at his medical care and unsure what he will do with the rest of his life.

One of more than 130 Washington residents who have been wounded in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Anderson personifies a hard truth about war: Enthusiastic patriotism often gives way to shattered lives.

The number of Washington wounded ranks seventh among all states, reflecting the state’s large military population. Nationally, 6,916 American troops have been wounded in Iraq, according to Pentagon figures published Tuesday.

The military estimates that an additional 57 military personnel from Washington have been wounded in Iraq, based on statistical analysis, because some soldiers’ records are incomplete. The Washington state numbers are as of July 24, the most recent state-by-state breakdown by the federal government.

The wounds range from life-threatening brain injuries that left Army chaplain Tim Vakoc in a coma to Anderson’s disabling injuries to a blast that redistributed body fat in Sgt. Richard Peters of Yakima.

Even when the wounds are relatively minor, such as the shrapnel injuries of 2nd Lt. Bryan Suits of Seattle, they cause disorientation and psychological trauma. In an e-mail message to friends, Suits described the moments after the mortar attack that left him wounded. “My bell is rung pretty hard. I don’t know it yet, but I’ll soon become easily distracted for 24 hours. A loud ringing is going to begin in about 20 minutes,” he wrote.

Anderson was wounded near Baghdad on April 6, 2003, when his reconnaissance unit was ambushed. He was shot in both knees, a thigh and his right shoulder.

Despite his wounds, Anderson said he would choose the Marines again to turn around his life. “It’s been the best four years of my life,” Anderson said. “I’m very glad I went to war.”

After he was wounded, Anderson returned to Spokane to a hero’s welcome, including a limousine ride to a free stay in the presidential suite of the Davenport Hotel.

But in a recent telephone interview, he was angry about the care he received at Bush Naval Hospital on the Marine base at Twentynine Palms, Calif. He says wounded Marines are treated as an inconvenience by the military, which tries to limit the expense of caring for them.

Anderson contends he suffered needless pain as Navy doctors debated how to treat his wounds. “Why did I suffer for 18 months?” Anderson wondered.

He recently found a private surgeon to perform arthroscopic surgery on his damaged knees. Scar tissue was removed, and Anderson is hoping he will walk normally soon. “I still run into walls,” he said.

Hospital spokesman Dan Barber declined to comment on Anderson’s case for privacy reasons. Patient complaints are investigated by a customer relations officer at the hospital, he said.

Before being wounded, Anderson often aced the Marine Corps’ physical fitness exam by running three miles in under 18 minutes and doing 20 pull-ups and 100 sit-ups. “I don’t have that anymore,” he said.

Anderson’s left knee still locks up, and it’s tough to walk up and down stairs. He also had to beat an addiction to painkillers.

Anderson no longer is considered fit for combat, and he left the Marines in August. He is in Spokane with his wife and 2-year-old daughter, living with his parents and looking for a job.

But at heart, he remains a Marine. “I swear to God if I had the knees, I’d be a lifer,” Anderson said.

It’s not uncommon for wounded soldiers to replace battles in Iraq with battles against the military medical system.

The military’s disability system mirrors workers’ compensation and long-term disability in the private sector. It pays people when they have illnesses and injuries that are job-related. Many soldiers misunderstand that pain by itself won’t win them compensation because pain is subjective and unmeasurable.

The Army says 56 percent of soldiers applying for long-term disability received a one-time lump-sum payment in 2003. Seventeen percent received nothing because they were declared fit for duty or suffered injuries unrelated to their service. Another 17 percent received temporary disability payments. Only 9.8 percent won long-term disability pay that lasts for life.

At Fort Lewis near Tacoma, 221 National Guard and Reserve soldiers are recovering from wounds and assigned to a “medical hold” unit until they return to duty or are discharged from the military. A similar unit for regular Army soldiers is at Madigan Army Medical Center there.

The soldiers in the Fort Lewis unit come from all over, although they tend to be mostly from the Western states, said Capt. Tealla Martin, executive officer of the unit.

The unit has had as many as 350 soldiers in the past year, staying an average of 91 days, she said.

Among those in the “medical hold” unit is Army Staff Sgt. Richard Peters of Yakima, who was wounded in late June when the truck he was driving was destroyed by a roadside bomb. Peters suffered shrapnel wounds to his left thigh, calf and hip and a broken front cranium that “filled my upper sinus cavity with body fat.”

Peters has been living at home in Yakima with his wife and two young daughters since July 5. Once a week he makes a three-hour drive to Madigan for treatment, a trip made more uncomfortable by his hip wound. A guard at the Yakima County Jail in civilian life, the reservist won’t be considered fit for duty again until later this month.

Peters loves bicycling, camping and other outdoor activities, but he doesn’t get around much these days. His legs are covered with bandages. He still has some shrapnel in his body that probably will remain because removing it is too dangerous. He also has some head pain from the explosion.

“I can’t do too much,” Peters said. “I hobble around the house.”

Some wounds barely take a soldier away from duty. Suits is normally a radio talk-show host in Seattle but has been serving as an information operations officer in Iraq. He gathers intelligence and tries to convince Iraqis that the U.S. occupation is to their benefit.

On July 1, he had just pulled into a base for lunch when a mortar round struck the ground near his vehicle. The steel casing disintegrated into thousands of shards of steel and wire moving at 4,000 feet per second.

“I’m enveloped in a hot acrid cloud, like the inside of a tornado,” Suits wrote. “I have the sensation of a fire hose shooting gravel at me.”

He suffered numerous cuts on his wrist and a bruise from a rock.

Taken for medical care, Suits was informed by a nurse that his blood pressure of 129 over 90 is high. He realized the nurse did not know why he was seeking medical attention.

“What happened?” she asked.

“We invaded Iraq,” he replied.