Lolo Trail may be getting lost

WEIPPE, Idaho – The Lolo Trail means different things to different people.

For many in America, it’s known as the most difficult and miserable portion of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s two-century-old journey through the steep and rocky Bitterroot Range between Idaho and Montana.

For Nez Perce Indians, it’s a trail system their ancestors used for centuries to hunt buffalo and trade with other tribes.

For Weippe residents Gene Eastman and his wife Mollie, it’s a mystery, a crusade and a passion.

The longest undeveloped portion of Lewis and Clark’s journey, the 126-mile trail corridor that starts at Lolo Pass in Montana and ends at Weippe is a National Historic Landmark. The U.S. Forest Service expects it to be visited by thousands during the next two years in conjunction with the anniversary of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

While the trail is clear and pronounced in many places, in others it has been damaged or obscured by fires, human use, federal forest management, changes in animal trails and new growth. The Eastmans fear that because no one clearly has identified the true original trail in its entirety, the route is being neglected, damaged or rerouted to provide access for tourists.

“I think the problem is with the Forest Service,” said Gene Eastman. “They’re thinking of it as a recreational trail, and I’m thinking of it as a landmark like Mount Vernon.”

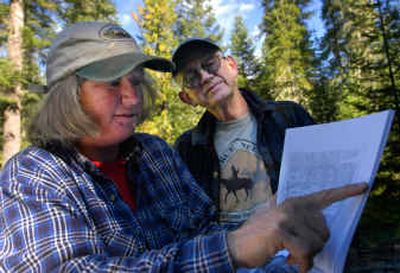

The 67-year-old retired Idaho Fish and Game officer has hiked in the forest since 1973 and is an expert at using old maps to find his way through wilderness areas. More recently, he has traveled into the woods with a walking stick and copies of maps dating back to Clark’s original renderings in 1805. His goal is to rediscover portions of the trail that experts claim are lost.

Logic suggests – and the original maps confirm – that the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery traveled the obvious routes of the Nez Perce, said Eastman. When he looks for the original trail, he looks for Indian trail characteristics. Their path was usually a straight line, not switchbacks, and they often followed mountain ridges because they were easiest to hike, he said.

Some of the trail segments that the Forest Service has marked today, such as the switchback section just a quarter-mile before the Lolo Campground, would never have existed 200 years ago, said Eastman, noting that Indian trails would have gone directly up and down hills.

Eastman also looks for ditches and places of compacted earth, where years of use have made the soil less hospitable for trees and brush. He said in many places the trail would be only about 40 centimeters wide, about the width of a horse’s pelvis.

He also watches for peeled trees, showing where the Nez Perce removed bark to feed themselves and their horses, and for cairns – rocks piled to serve as markers. He also uses landmarks left or noted by some of the early trail hunters over the past century.

Eastman said a percentage of the trails and campsites that the Forest Service has marked as original don’t agree with the Lewis and Clark documents or what previous researchers found.

While well-worn pathways and the expeditioners’ journals make some portions of the route clear, in many places it’s impossible to be sure exactly where Lewis and Clark and those traveling with them walked, say forest officials.

People have been looking for the trail since before the centennial anniversary of the expedition, said Chris Jenkins, archaeologist for the Clearwater Forest. There are many trail-seekers and many theories.

“It’s one of those things that we’re not all going to agree on,” he said, adding that it is debatable whether finding the exact trail is even possible.

Eastman believes the Forest Service has altered and relocated portions of the trail for recreation and land management reasons. While he agrees that some parts of the original trail might be very difficult for most people to find, he doesn’t like the fact that visitors may not realize the trails they’re using aren’t Lewis and Clark’s. “People should know if they’re really hiking the trail,” he said.

You don’t bury Gettysburg or relocate the Battle of Little Bighorn, so why would you move the trail, asked Mollie Eastman.

The Forest Service is simply trying to designate one trail for hiking among the existing network of trails, said Jenkins. While they may not be the expedition’s precise route, “these are existing trails that have been out there and have been used historically,” he said.

Switchbacks are put in place for safety and to control erosion, but “nobody is going to pretend that is exactly the trail,” he said. “I don’t think most people are worried about finding the exact location of the trail. But they can stop at places that we know are close to where Lewis and Clark did something.”

Eastman believes that if he can find segments of the trail with his Global Positioning device and some old maps, finding and protecting the true trail should be possible with modern technology and archeological expertise.

But there are some segments that have already been changed irrevocably. In one area, the trail was modified years ago to accommodate public camping. In others, it was moved for paved roads and new segments were built for public access.

Some of the greatest damage took place in the 1930s, when part of the trail was bulldozed for the building of the Lolo Motorway, also known as Forest Service Road 500, said Aaron Miles, natural resources manager for the Nez Perce tribe.

For the Nez Perce, the trail is less about American history and more about the culture and legacy. It’s viewed as a sacred place. “We called it the old buffalo trail. It was highly used,” said Miles. “Lewis and Clark was just one caravan that went through.”

The trail system was also a key site during the Nez Perce War in 1877, when five bands of the tribe crossed the Bitterroots to evade U.S. Army efforts to move them onto a reservation.

Some of those Nez Perce were later moved more than 100 miles north, to the Colville reservation. Their descendants today have never set foot on the trail system, though it’s still important to them, said Charlie Moses Jr., treasurer of the Nez Perce Historic Trail Foundation.

These Nez Perce see the trail system as hallowed, sacred and sad, he said. “It’s another part of our past that can make or keep us whole.”

He said that the Forest Service should do its best to limit changes to the trail and protect it for the Nez Perce and for posterity. “It’s not a scenic trail or a hiking trail,” he said. “It’s a historic trail. There is a difference.”

While the Forest Service doesn’t completely agree with the Eastmans’ assessment of the trail location or its management, the agency welcomes their interest and passion, said Keith Thurlkill, the Forest Service regional interpreter. “We all agree on the value of the trail,” he said. “The rub is what to do with it.”

One morning last week, Gene and Mollie Eastman hiked up a small portion of the Forest Service trail near the Lolo Campground about 20 miles out of Weippe. Gene Eastman stopped on the switchback to point out what was a more likely route for Lewis and Clark’s group.

“You can see bits and pieces of the real trail,” he said, pointing to a subtle path that ran straight down the hill. “It’s not much to look at. But I think there’s something to protect here.”