Monumental loss

NEW YORK – Davis “Deeg” Sezna Jr.’s friends gathered in different cities Saturday to drink Bloody Marys and play a round of golf in his memory.

Sezna was two weeks into his job as a trader for a stock brokerage on the 104th floor of the World Trade Center’s South Tower on Sept. 11, 2001.

He saw that the North Tower had been hit at 8:46 a.m. by an airplane, and he was going to leave his building as a precaution. But the hard-working overachiever wanted to wait until the New York Stock Exchange opening bell rang at 9 a.m.

At 9:03, a second plane piloted by terrorists hit the South Tower, killing 23-year-old Sezna and hundreds of others.

“He was excited to have that job,” David Turley said at the site of the attacks Saturday. “He really thought he’d made it.”

At Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, where the men were fraternity brothers, Sezna often would set out a bar and serve Bloody Marys to friends. He also loved golf, following in the footsteps of his father, a professional golfer.

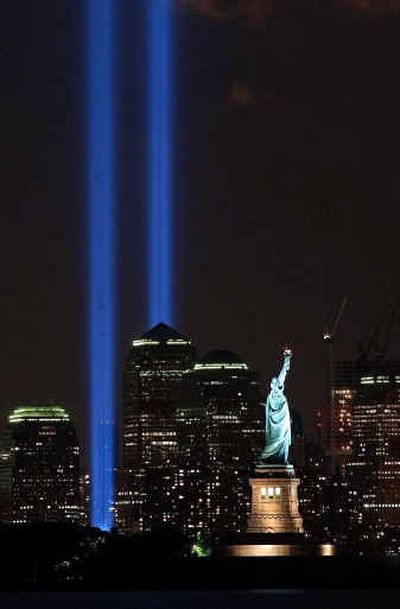

Sezna was one of 2,749 killed that day in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania. Thousands of New Yorkers descended on ground zero Saturday for the third annual memorial ceremony on what President Bush has declared Patriot Day. Parents and grandparents of victims read the names of the deceased; children had the honor last year.

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg told the crowd there’s a name for children who lose their parents – orphans – and there are names for people who lose their spouses – widows and widowers.

“There is no name for a parent who loses their child, for there are no words to describe this pain,” he said.

Alok Mehta’s father showed that pain without a single word. Stopped by a reporter on the way to the ceremony, he could only nod his head when asked if he’d lost a loved one. Struggling to hold a large bouquet of flowers, he pulled two sheets of paper from a bag: a petition to resume the search for missing people and a flier with a photo of 23-year-old Mehta, who worked for Cantor Fitzgerald, a financial services company.

Your son? A second nod, and then the man walked a few feet away, rested his head on a store window and sobbed.

The grief was tangible at ground zero. It weighed down the faces and the bodies of the people gathered around the site. “You can feel it in your legs,” said Paul Capetillo, 24, another friend of Sezna’s, as he trudged along.

Three years ago, New Yorker Jana VanSingel watched the attacks from her office building a few blocks from the World Trade Center. “You could hear it, and you could smell it,” she said. “It was a loud, deep thunder.”

VanSingel moved to New York from Michigan three years before 9/11 and was on the telephone with her worried parents during the attack. She didn’t move back home, though. “I felt an allegiance to stay,” VanSingel said. “But if it happened again, that’d be it.”

Turley moved to the city after his friend was killed.

“I guess I’ve always wanted to make it big, too,” he said.

City of distinction

New York is a city of contrasts. Celebrities own luxurious apartments in neighborhoods where a morning jog means tiptoeing around homeless people. The city has the crime rate of a major metropolis, but standing on a street corner at night feels safer than a walk through downtown Spokane. The people walk fast and stare straight ahead, but stop someone for directions, and they’ll linger with a warm reply.

Shimi Rotches moved to New York after 9/11 to “take a break” from the violence in Israel, his native country.

“We both know the same thing,” said Rotches, 23, of his new neighbors and his old countrymen.

Near Rotches, an argument ensued between a peace activist, a 9/11 conspiracy theorist and a man who supports President Bush’s actions since the attacks. The discussion grew louder just as a moment of silence commemorating the attack on the South Tower began. A woman stormed toward the trio, tears streaming down her face.

“Show some respect,” she barked, silencing the group.

Most people at ground zero on Saturday didn’t want to talk politics. Fewer than 10 were seen holding political signs or heard shouting their views. Many people agreed that the memorial wasn’t the place for it.

“They have the right to do what they’re doing,” George Washburn, of Pennsylvania, said of the few activists. “But that makes you feel very angry.”

The most common emotion Saturday was sadness. Family members cried openly as they talked about traditions their families hold to keep victims’ memories alive. They said they’re moving ahead, but not forgetting. Elsewhere in the city, life forged forward. A man whistled down a cabbie. A vendor pushed tourist T-shirts. And Grand Central Station shuffled people in and out of the city.

On one of the subway trains, a woman read a book. Her young son stared straight ahead, already mastering the New York City gaze.

Still reading, the woman reached over and tickled the boy. His eyes switched from dead to dazzling, like a sign in Times Square.