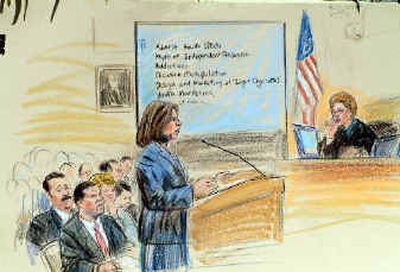

Tobacco trial opens

WASHINGTON — Tobacco companies, desperate to maintain their hold on tens of millions of American smokers, worked together for decades to deceive the public about the dangers of cigarettes and to encourage the young to start puffing, government lawyers said Tuesday at the start of a racketeering trial.

Justice Department lawyers pointed to numerous statements by industry executives that created doubt among smokers about whether the habit was harmful and whether they really needed to kick it.

“Defendants’ strategy of denial worked, and they knew it,” Justice lawyer Sharon Eubanks told U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler.

The government wants new restrictions placed on the industry and is seeking $280 billion it claims the companies earned through the alleged fraud, a record amount for a civil racketeering case. Tobacco lawyers say such an amount would bankrupt the companies, and the government isn’t entitled to any money.

The defendants are Philip Morris USA Inc. and its parent, Altria Group Inc.; R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.; Brown & Williamson Tobacco Co.; British American Tobacco Ltd.; Lorillard Tobacco Co.; Liggett Group Inc.; Counsel for Tobacco Research-U.S.A.; and the Tobacco Institute.

The companies will present opening statements Wednesday. Philip Morris attorney William Ohlemeyer said the industry had heard all the evidence the government put forward Tuesday in previous cases.

He said the government’s case is too focused on past behavior to succeed. Ohlemeyer, who denied fraud had occurred, said it would be impossible for the government to prove future wrongdoing is likely to occur, which the law requires.

“Cigarettes aren’t sold the way they were sold in the past,” Ohlemeyer said.

He noted agreements worth $246 billion that the industry reached with all the states in the late 1990s imposed sweeping restrictions on how cigarettes are marketed. For example, companies can’t rely on billboard, transit or cartoon ads the government alleges have been used to attract teens.

The Clinton administration filed the lawsuit in 1999, and the Bush administration pursued it after receiving early criticism for openly discussing the case’s perceived weaknesses and attempting to settle it.

The government has spent $135 million on the case so far.

Scientific studies dating to the 1950s said smoking could lead to cancer and other health problems. In 1964, the U.S. surgeon general issued a report linking smoking to lung and larynx cancer and chronic bronchitis.

Still, the government’s lawyers pointed to numerous statements in which tobacco executives denied such links. They showed Joseph Cullman, former chairman of the Philip Morris board, saying in a 1971 television interview, “We do not believe that cigarettes are hazardous. We don’t accept that.”

Justice lawyers said the industry created now-shuttered organizations to rebut findings about smoking and the dangers of secondhand smoke and to conduct public relations campaigns to create uncertainty about whether smoking was harmful.

“The problem to them was that the public might stop smoking because of health concerns,” Justice lawyer Frank Marine said.