Remains of early stealth hunter found

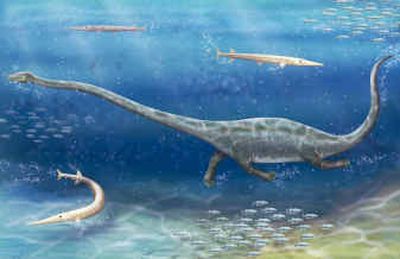

WASHINGTON – A newly discovered fossil may be the remains of one of the first stealth hunters, a swimming dinosaur that could use its long neck to sneak up on prey and strike without warning.

Once a resident of a shallow sea in what is now southeast China, the newly found reptile with fangs would have hunted in murky waters, its small head extending far from the bulky body that fish would have recognized as a predator.

“The long neck would allow it to approach prey without the whole body becoming visible,” said Olivier Rieppel of the Field Museum in Chicago, a co-author of the report.

The new fossil was discovered by Chun Li of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2002. The creature is described by Li and colleagues in this week’s issue of the journal Science.

Li named the new dinosaur, which lived about 230 million years ago, Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, meaning terrible headed lizard from the Orient.

With a body about three feet long and a neck adding five and a half feet – the newly named creature is related to Tanystropheus, another long-necked reptile that lived in the area of Europe and the Middle East.

But the researchers said the new dinosaur had 25 neck vertebrae, more than twice that of Tanystropheus, and in Dinocephalosaurus they were not as elongated. It had rib-like bones parallel to the vertebrae.

They are both members of a diverse reptile group called the protorosaurs, which have long necks and elongated neck vertebrae. For years scientists have wondered at the purpose for the long necks in this group of animals.

“This is important research because we have finally explained the functional purpose of this strange, long neck,” said Rieppel, head of geology and curator of fossil amphibians and reptiles at the Field Museum.

As Dinocephalosaurus approached in murky water, its prey would have been aware only of the relatively small head, not the full-size profile of a predator.

Michael LaBarbera of the University of Chicago, a co-author of the report, said the rib-like bones along the side of the neck may also have played a role in hunting.

Those bones give the neck some stiffness, Rieppel explained. It could flex, but not like a snake.

According to LaBarbera, contraction of the creature’s neck muscles could have rapidly straightened the neck and splayed the neck ribs outward.

That would have greatly increased the volume of the throat, allowing the animal to lunge forward in the water at prey. Ordinarily, lunging through water creates a pressure wave that a fish can sense, allowing it to flee. But the researchers said that by suddenly enlarging its throat Dinocephalosaurus could, in effect, suck in and swallow its own pressure wave, giving it the ability to strike without warning.

“It allowed an almost perfect strike at prey, which usually consisted of elusive fish and squid,” Rieppel said.

It’s a process similar to the suction feeding done by some fish and turtles, Rieppel added.

“Feeding underwater in a dense medium is always a problem, and suction feeding is an elegant solution,” he said.