Districts woo home-schoolers

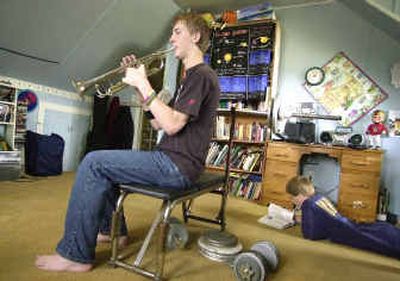

MYRTLE POINT, Ore. – One day after jazz band practice, 14-year-old Peter Wilson’s band teacher pulled him aside for a chat.

The instructor wanted to know whether Wilson, who is home-schooled alongside his three brothers, liked being taught by his mother, and why he didn’t come to public school full-time, instead of just for music programs.

His teacher seemed uncomfortable, Wilson said, and the interview was brief. As soon as he got home, the teenager told his parents what had happened.

For Mark and Teckla Wilson, who are raising their four sons in Mark Wilson’s roomy childhood home in Myrtle Point, a former timber town not far from the Oregon coast, the teacher’s inquiry was an eyebrow-raiser.

“I thought I should find the motive, or the reason for it,” Mark Wilson said. “I thought it could come across as making my children feel the need to justify their home-schooling.”

It didn’t take long to discover that the teacher’s questions were part of a larger effort by the Myrtle Point school district to persuade home-schooling families in the area to give the public school system a shot.

Enrollment’s been dropping steadily in the district as timber jobs have dried up, and Oregon’s state budget cuts have left Myrtle Point facing a $675,000 funding gap for next year.

Since Oregon bases its state school funding on enrollment numbers, every home-schooled child that Myrtle Point can woo means an extra $5,000 or so for the school’s bottom line. District estimates are that about 100 kids living in the district are home-schooled, which could bring in up to $500,000.

Already, about 18 percent of the nation’s 1.1 million home-schooled students are enrolled at least part-time in public school, usually for specialty courses like music, art or science that are more difficult for parents to teach at home. But that’s usually the parents’ choice, not the result of a recruitment effort by strapped-for-cash public schools.

Myrtle Point’s not the only district pursuing such a strategy, whether elsewhere in Oregon or across the country. In Fort Collins, Colo., for example, elementary students in the Poudre school district go to a local school twice a week for art, science and music programs; in 2003, that was enough to earn the district an extra $203,341 in state per-pupil funding.

And in Walla Walla, school officials have launched plans for a new learning center that they hope will attract at least 30 home-school students, to help cope with a projected $200,000 in budget cuts for the 2005-06 school year.

But there are no guarantees that the strategy will work. Many home-school parents are fiercely loyal to the lifestyle, and to the educational benefits they see for their children. Some shy away from the peer pressure and drugs they fear are rampant in public schools; others, like the Wilsons, want to home-school in part for religious reasons.

“I like instruction where the instructor, not just the body of knowledge, is important,” Teckla Wilson said. “Home-schooling allows you to work out the pace that is best for them. And we are Christians, and for me, it is important that I teach them to think with a biblical world-view.”

After Mark Wilson’s complaint, Myrtle Point school officials told teachers not to speak directly to home-school students about recruitment efforts. Instead, parents got letters from the school district, inviting them to attend a dinner and hear about new classes the school is adding to appeal to the home-school population.

Lynn Potter was one of about 30 home-school parents who went to the dinner; her daughter, who plays in the school’s band, was even part of the evening’s entertainment. She said she’s grateful that her children are allowed to participate in music and sports, but that there’s nothing the district could say to get her to give up home-schooling.

“There would be the moral issues that our children would have to face with all the others who aren’t taught the way they are,” she said. “It’s a lot of work, it is hard, but I am committed to five more years of home-schooling.”

Robert Smith, the district’s superintendent, knows he is facing an uphill battle. He knows he could face criticism for putting pressure on home-school families, and said he’d be happy even for families just to enroll their children part-time.

To that end, the district is trying to phase in some courses that officials think would be particularly appealing to home-school parents, like forestry, ecology and computer sciences.

The district also has plans to start up an alternative high school and add more vocational classes, like welding and agricultural mechanics, hoping to keep some students who have dropped out.

Smith said the district is also willing to make some curricular adjustments to appeal to home-school families – for example, allowing previously home-schooled students to discuss the theory of creationism during biology lessons on evolution, or biblical literature in English courses.

“We wouldn’t say what they have to believe – we don’t establish any certain religious dogma in our school district,” Smith said. “We would just encourage them to develop skills of debate, discussion and research.”

And he said school administrators are willing to work with home-school parents on preparing individual plans for home-school students making the transition and to assign mentors to such students.

If these measures don’t work and if the enrollment decline persists, Smith said the Myrtle Point district may have to declare bankruptcy.

The fate of the school has provoked plenty of discussion in the town of 2,712, and prompted a tart opinion column by school board member Dal King in the weekly Myrtle Herald.

“Families who home school or choose to send their kids to other districts, we need your full support, not just what’s convenient for you,” King wrote. “While you may have good reasons, please do your part by enrolling your kids full-time in the district and don’t just ‘cherry-pick’ music or sports.”

For Mark and Teckla Wilson, that dig was personal – especially since Mark Wilson’s parents both taught in the district, and the family has always supported the district’s request for school levies.

“They underestimated that commitment that most home-schoolers have made,” Mark Wilson said. “We do this at some cost to ourselves. If the kids were all in school, my wife could get a job. To think that by offering us a few courses, by dining us, they could get us to say, ‘Oh, never mind,’ is unrealistic on their part.”