Allegations riddle mother’s past

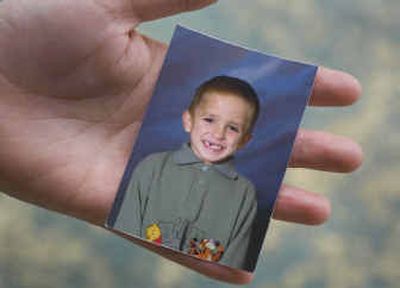

On the day before his death in January, a skinny 6-year-old named Tyler Joseph DeLeon made a hole in the screen window of a home in southern Stevens County to eat the snow piled outside.

Carole Ann DeLeon, 50, offered the story as evidence of her adopted son’s bizarre eating and drinking habits, according to state documents.

But court records and documents from the state’s Child Protective Services say investigators can find no medical documentation of Tyler having an eating disorder. His pediatrician’s office said Tyler had no medical restrictions on his food or drink, according to a CPS record filed after the boy’s death.

“I think the little kid was so hungry he just tried to get away,” said a person close to the case who extensively reviewed Tyler’s file and expressed an opinion only on the condition of anonymity.

The anecdote is at the heart of the boy’s death and the criminal investigation into DeLeon and her 28-year-old daughter, Christina Burns-DeLeon.

Tyler, who reportedly had the flu, weighed just 33 pounds when he died Jan. 13, his seventh birthday, and was severely dehydrated, according to an initial finding from the medical examiner’s office and court records. The office said the boy may have died of natural causes, according to CPS records, and the final cause of death may not be available for weeks.

But Stevens County Sheriff’s Office reports list both DeLeon, who works as a paralegal with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Spokane, and Burns-DeLeon as suspects in the boy’s death. Neither DeLeon nor her daughter has been charged in the case, which has been handled as a “homicide-by-abuse and criminal mistreatment investigation,” according to a search warrant filed in Stevens County last month.

Last month, the state removed four remaining children from DeLeon’s home.

DeLeon’s attorney, Carl Oreskovich, said she has cared for children in her home for years.

“People that know her and have been around her are just flabbergasted by the nature of these allegations,” Oreskovich said. DeLeon regularly took Tyler to a doctor and there were no indications that he was malnourished, Oreskovich said.

“Tyler’s death was tragic,” Oreskovich said. “She has been placed under the microscope in terms of having every bit of her life scrutinized. She knows and her family knows that the allegations are not true.”

‘Signs of abuse’

In the weeks after Tyler’s death, investigators from both the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office and the child welfare system began to review piles of documents stretching back more than 15 years and interviewed people who came into contact with the DeLeon family.

The Spokesman-Review obtained hundreds of pages of court documents, accounts of calls to the agency about concerns at the home, and the state’s records of its investigation after Tyler’s death.

The documents provide conflicting views of DeLeon, who applied to be a state-licensed foster parent in 1996. One former foster parent told the agency that DeLeon was a “saint,” according to the CPS records.

But records from the agency’s investigation into Tyler’s death and Stevens County court documents report multiple allegations that DeLeon withheld food from children in her care. Oreskovich called the allegations “totally untrue.”

The agency received at least eight referrals of problems at the home since 1996, including reports of bruises, a broken bone and a burn on another boy’s face. In each case, the agency determined that the allegations were either inconclusive or unfounded – meaning investigators did not believe abuse or neglect had occurred.

The state gave DeLeon a license and paid her to care for foster children despite the fact that three children left her home in the 1980s after allegations of abuse and neglect, according to the search warrant and Wyoming court records.

That included a 1988 case in which a 12-year-old girl was removed from DeLeon’s care after the girl reported being tied up by DeLeon and her then-boyfriend and left in a basement overnight as punishment for eating three packages of string cheese, according to documents filed in the search warrant.

The agency said it destroyed the 1988 record as part of a routine expunging of unfounded reports – even though a physician found evidence of rope burns, belt marks and bruises on the girl. The physician said the girl showed “definite signs of abuse” and called the case “shocking,” according to documents in an affidavit for a search warrant filed last month.

Oreskovich said the girl would “intentionally injure herself.”

The agency did not intervene last spring when a state investigator “strongly recommended” that Burns-DeLeon no longer have contact with the children. An agency spokeswoman told The Spokesman-Review that CPS cannot comment on the details of the ongoing investigation.

“As soon as we can release files and information, we will,” spokeswoman Kathy Spears said last week. “We will give full public disclosure of how this case was handled and who was involved.”

On Jan. 4, nine days before his death, the agency received another referral about Tyler after he arrived at Lake Spokane Elementary School with bruises on his face, according to its records of the episode. The boy told the teacher he fell on the stairs but otherwise refused to discuss the injuries, according to records.

The agency did not visit the home in the nine days before Tyler’s death on Jan. 13. The agency’s policy says social workers have 10 days to respond to a report.

Three weeks after Tyler’s death, DeLeon called a CPS worker to express her frustration with the case, according to the agency’s service episode report, dated Feb. 7 of this year.

“(Tyler) was a special needs child, and they put these children in your home and expect them not to have problems and crucify you when they do …,” DeLeon told the CPS worker, according to notes of the conversation.

The records state that DeLeon said, “I told them that the problem is gone. Ty is dead. He was always the problem. He lied. The one time the little shit is honest falling on the stairs and then there are problems.”

‘He had some problems’

To her friends and family, Carole Ann DeLeon was a model foster parent who welcomed some of the most troubled children in the state’s child welfare system into her rural southern Stevens County home. From Nov. 1, 2004, to Feb. 28, DeLeon received $10,388.43 to care for the children, according to an agency report.

“I have never seen anybody as devoted to their children as Carole,” said Larry Bell, a friend and former foster parent.

Bell said Tyler loved swimming, watching cartoons and going to Chuck E. Cheese’s, a child-themed pizza parlor.

Bell said the boy was a “sweetheart” but also had behavioral problems, including pulling out his own hair.

“We just loved him to pieces,” Bell said. “He had some problems that most people would not have been able to put up with.”

At Lake Spokane Elementary School, DeLeon told the school that Tyler threw screaming tantrums, tried to drink from the toilet, lied about abuse and tried to injure himself, according to notes from interviews with a sheriff’s detective in a Feb. 5 incident report on the boy’s death. School officials said the boy was quiet and polite, and he did not exhibit the behaviors that DeLeon reported, according to the documents.

According to CPS investigative records, DeLeon expressed similar concerns about another foster boy in her care. CPS records include reports that DeLeon placed an alarm on that foster boy’s door to alert her if he tried to leave the room at night to eat or drink, and turned off water valves to prevent him from drinking water.

DeLeon instructed Tyler’s teachers to strictly monitor his eating and drinking: Even though the boy appeared to be undersized and skinny, he typically received a slice of bread with peanut butter and a thermos of milk for lunch, according to the search warrant.

Others – including a former friend, school teachers and another foster parent – expressed concern about DeLeon’s treatment of some of the children in her care, according to the reports.

At Lake Spokane Elementary School, one teacher said the boy was “dressed like a ragamuffin” and had the most injuries “she’d ever seen on a kid in her 14 years of teaching,” according to a sheriff’s report.

Another teacher said DeLeon instructed her to “push Tyler away if he initiated any affection to her because he was just using that to be in control,” according to the report.

According to the sheriff’s report, a former principal at the school told the detective: “Tyler had a lot more bruises than the other children. Tyler had told the teachers his mom had pushed him and Christina would kick him down the stairs because he would not get his coat and shoes on fast enough.”

The former principal also said DeLeon instructed a teacher not to pay attention to the boy if he started to say he was injured, according to the sheriff’s report.

“Carole also told me if she ever started beating him, Tyler, he would be dead because she wouldn’t be able to stop,” the principal told the Sheriff’s Office, according to the report. “Carole further stated the doctor had given her credit for not beating him.”

DeLeon told another school employee that Tyler had “impulse control problems, agitation, defiance, screaming fits and increased lying,” according to the report.

A school employee told the detective that “Tyler would always ask politely for a drink and only drank as much as any of the other children, although sometimes he said he was very hungry.”

A teacher said DeLeon promised to provide medical reports about Tyler’s condition, but the school never received any medical documentation, according to the sheriff’s report. CPS records state that a nurse at the office of Tyler’s pediatrician, Dr. David Fregeau, “reported no mention of Tyler having restrictions on food and/or liquid,” according to a Feb. 4, 2005, CPS service episode record.

When the detective asked DeLeon for doctors’ reports on Tyler’s condition, “Carole immediately told me any parent could see if a child was having an eating and drinking disorder. I told Carole as of this date I have not found any documentation from a doctor of the boys having an eating and/or drinking disorder,” according to the sheriff’s report.

Gaining weight

DeLeon told several people that a second young boy in her care for several years had a similar eating and drinking disorder, according to CPS records and interviews.

In October 2004, that boy moved into a new foster home, where he was awaiting adoption. His social worker, Loretta Mea, instructed the foster parent to closely monitor the boy’s food and liquid intake, according to notes from an interview with the foster parent.

But the foster parent, who has raised several other children, said the boy seemed to have a normal, healthy appetite, according to the agency’s episode record.

In fact, the boy’s new physician identified him as underweight and malnourished, according to the agency’s service records.

“I feel that (the boy) has been severely malnourished over the past couple years, and this has contributed to (if not caused) his growth delay and weight gain,” a naturopathic physician wrote on Oct. 29, 2004, according to agency records.

Four months later, the boy had gained 18 pounds and grown 2½ inches, according to the records.

When contacted last week, the foster mother said the agency had instructed her not to discuss the case publicly.

Concerns raised

When Carole DeLeon arrived in Washington in the 1980s, she was fleeing an abusive relationship, according to Wyoming court records.

DeLeon moved from Wyoming into a home in Nine Mile Falls with her two teenage sons, a boyfriend and a 12-year-old girl in her care, according to reports from CPS and the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office.

In the spring and summer of 1988, the Sheriff’s Office received multiple reports of abuse and assault at the home, which eventually resulted in all three children leaving the home, according to court records.

The search warrant includes an allegation that DeLeon and her boyfriend at the time, Chris Wear, bound the wrists of the 12-year-old girl and left her in the basement overnight as punishment for eating three packages of string cheese.

A CPS investigative record says medical tests indicated the girl suffered from dehydration. A physician found rope burns on her wrists, belt marks on her buttocks, and bruises on her face and thigh, according to the search warrant.

An April 25, 1988, CPS record said the girl was “tormented, treated without regard to human dignity … (and) belittled.”

In an interview that month, the girl reportedly told a state investigator that after she accidentally spilled goat food, DeLeon served her the goat food for dinner.

When questioned by a sheriff’s deputy, DeLeon and Wear said the girl “lies constantly and steals on a continuous basis,” according to an incident report filed with the Sheriff’s Office.

In an April 28, 1988, letter to a state social worker, area supervisor Barbara Paccerelli expressed concern about the treatment of the girl in the home.

“We have reports of isolation and seclusion, of Mary not allowed to speak to the neighbors, to the extent that last week, she said ‘Hi’ to a neighbor’s dog and was made to return and apologize to the animal for speaking to it,” Paccerelli wrote.

The agency removed the girl from the home and sent her back to Wyoming, according to records.

Yet problems continued at the home, according to documents from the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office.

In July 1988, a sheriff’s deputy responded to a fight at the home. DeLeon, her two teenage boys and Wear all appeared to be injured. Her son John had a bloody nose, cut lip and bruises on his face, according to the deputy’s report.

“The level of violence is increasing in this home,” the deputy wrote. “If things remain the same and the boys go back into the home, the possibility for serious injury or death to one of (the) family members is very high.”

John DeLeon, then 14, filed a court petition to be removed from the home. He later attended Harvard Law School and now works as an attorney in Wyoming, where he does public defense work and represents children in state placements, according to the report. Carole DeLeon said the boys were angry about having to move to Washington, according to her affidavit in the case.

“I want both of them to be safe, healthy and happy in our home,” Carole DeLeon stated in the affidavit.

In a telephone interview with CPS after Tyler’s death, John DeLeon described his mother as “very articulate and very convincing,” according to the agency’s record of the conversation.

“She must be at the center of attention,” he reportedly said, “and everyone must comply with whatever she wishes.”

Tyler’s life

In 1999, three years after the state granted DeLeon a foster license, the agency received its first report about Tyler, according to the agency’s intake records. In June, DeLeon reported the toddler threw himself backward into a wall, resulting in a broken leg, according to CPS records.

According to caseworker notes, DeLeon called the social worker, who was “unaware that an incident report had to be filed.” The agency reported that Tyler’s doctors were not concerned and that the boy “had a history of throwing himself backwards.”

By the time the agency investigated the injury in September 1999, the boy’s cast had been removed, and the state worker noted that the agency didn’t suspect DeLeon of intentionally hurting the boy.

“What I do know is that there were many times that allegations were made, and they were investigated and found to be unsubstantiated,” said Oreskovich, DeLeon’s attorney.

A former friend of DeLeon told the state she ended her friendship with DeLeon in 2002 “because she could not tolerate how she treated the children,” according to CPS records of the conversation. She said she had reported her concerns earlier to CPS investigator Bob Tadlock.

The woman told the agency that Tyler was “singled out to receive the brunt of Carole’s anger and unhappiness.” She reportedly said that DeLeon would make the boy sit on the toilet for hours and exclude him from family activities like sitting in the hot tub, according to CPS records.

Last spring, Tadlock visited the home to investigate burn marks on the face of one of the foster children. Tadlock reported that Christina Burns-DeLeon became upset and yelled at him, according to CPS records. Tadlock reported that Burns-DeLeon did not comply with his request to put down a chisel she held in her hand, according to agency records.

Afterward, Tadlock told his supervisor in Olympia, “I strongly recommend that Christina no longer have contact with these children,” according to CPS records of the incident.

But Burns-DeLeon continued to care for the children, according to CPS records. The agency said it cannot discuss what happened to Tadlock’s recommendation.

Even though social workers were assigned to the home, the records indicate the state did not always know how many children were living there or that DeLeon had arranged an adoption through a private company, Spokane Consulting and Family Services.

‘No reply’

The documents provide few details into the final days of Tyler’s life.

On Jan. 12, the boy made a hole in the window screen to eat the snow, according to a CPS program manager.

The next day, Burns-DeLeon took care of the boy, according to a sheriff’s report. The report said Tyler was vomiting and saying he was cold.

At some point, DeLeon returned home from work and Tyler’s condition appeared to worsen, according to a sheriff’s report.

DeLeon called 911 at 4:26 p.m. to say that Tyler was not breathing, according to court records. He was rushed to Sacred Heart Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead 90 minutes later.

Hospital records at the time of his death say he had been sick one day with the flu. His skin was cool to the touch, and his body temperature was 93.7 degrees, according to a two-page medical report.

A medical examiner in Spokane determined the boy had a bruise on his head, an abrasion on his leg and minor scratches. Tyler was found to be “severely dehydrated,” possibly because of a stomach flu, according to CPS records.

After Tyler’s death, a school counselor recounted injuries she had noticed on the boy’s face nine days before his death, according to a sheriff’s incident report. The counselor said the bruises “looked like someone grabbed Tyler’s face with their hand real hard,” according to the report.

Records from the CPS investigation indicate Tyler’s teacher, Sandra Byers, was also concerned. The boy said he fell down the stairs, according to the agency’s records.

“I remember saying to him that it didn’t look like falling-down-stairs bruises,” Byers reported, according to CPS records. “He just looked at me and made no reply.”