Learn about a legend

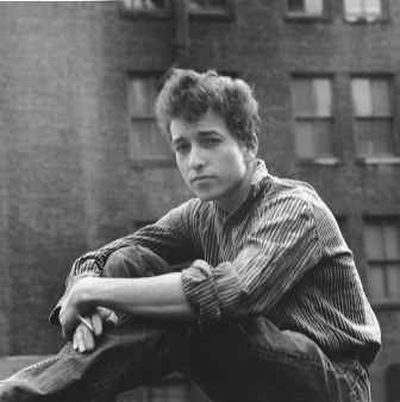

SEATTLE – Bob Dylan as a museum piece?

Well, why not? He’s already been a folk singer, a rock star, a myth, a legend, a recluse, an actor, a best-selling memoirist and, of course, the Voice of His Generation – though he vehemently denies the last charge.

He’s a mystery inside an enigma wrapped in a persona that we’ve been trying to solve ever since he left Hibbing, Minn., nearly half a century ago, bound for glory.

Now Seattle’s Experience Music Project, the brainchild of Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen, has weighed in with the first major museum treatment of Dylan’s life and times.

It runs through Sept. 5. Sometime after that, EMP curator Jasen Emmons is hoping, the National Museum of American History might consider hosting it.

Memo to the Smithsonian: Don’t think twice, it’s all right.

From the wall display of 100 different artists’ cover versions of “Blowin’ in the Wind” that greets you at the entrance (you can push a button to hear a punk-rock take or Marlene Dietrich vamping it up) to the mesmerizing, show-ending film clip of Dylan improvising nonsense lines, “Bob Dylan’s American Journey, 1956-1966” manages to be simultaneously thoughtful and entertaining.

It has something for everyone, nonfans and Dylan obsessives alike – though it’s no doubt more rewarding for those who can at least hum a few bars of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Here, for example, is the battered Martin guitar that 18-year-old Robert Zimmerman acquired in Minneapolis in 1959 and played for the first couple of years of his Greenwich Village career.

The important thing to know is that he got it by trading in the electric guitar he’d brought with him from Hibbing. Contrary to legend, Dylan was into rock – particularly Little Richard and Buddy Holly – before he turned into a folk singer.

Here is a set of wall-mounted headphones through which you can hear never-released material from Dylan’s first real concert, in November 1961 at Carnegie Chapter Hall. He sings one of the first songs he ever wrote, about an old man found dead on the street. The show’s producer lost money but paid Dylan $10.

Here is a copy of his first album, “Bob Dylan.” He has autographed the cover for a fan and included a snatch of lyrics (“Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song”) above his signature. Similar signed album covers appear throughout the show.

“It’s as if he’s telling us, ‘Pay attention to what I’m saying – it’s the words that are really important,’ ” Emmons says.

The exhibit is full of words, not the least of which are drafts of song lyrics. The penciled draft for “Blowin’ in the Wind” includes an editing mark switching the order of the second and third verses. (Dylan’s handwriting is surprisingly neat.)

In the typed lyrics of “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” the writer self-consciously spells “you” as “yuh.”

Beyond such minutiae lies the larger contribution Dylan made by marrying original, poetic lyrics to both folk and rock music.

“If he hadn’t done that first,” says the late folk icon Dave Van Ronk in a video interview, “the singer-songwriters of today just wouldn’t exist.”

As for music, there’s plenty of that as well.

The exhibition includes listening booths featuring the seven albums Dylan put out during the incredibly fertile four years between his 1962 recording debut and 1966’s “Blonde on Blonde.”

People who don’t know their Dylan can hear key songs from each album. Those who do can push the button that gives them a rare outtake or bootleg. And those who simply cannot stand the man’s, um, distinctive voice – Emmons, who’s 41, admits to being such a person when he was young and foolish – can choose a cover version: the Byrds, for instance, harmonizing “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

There’s great video, too. Once the museum had persuaded Dylan and his camp to sign on, it got access to a huge archive of footage being used by director Martin Scorsese to make a PBS documentary (it’s scheduled to be shown in July).

By combining this with other material – most notably D.A. Pennebaker’s “Don’t Look Back” and “Eat the Document,” a rarely screened film shot on Dylan’s 1966 tour – EMP was able to produce 25 minutes of concert footage for its main theater, plus four mini-documentaries for the exhibition itself.

“Everybody’s gifted,” says folk queen and onetime Dylan love interest Joan Baez, but “there are some people who crash through all the barriers with their gift, because it’s a particular one, it’s unique and it’s enormous.”

Images of the Gifted One assembled by EMP include footage from the famed 1965 Newport Folk Festival, at which the newly electrified Dylan either was or was not roundly booed (it’s hard to tell from the tape, and Dylanologists still debate the question). At one point, back in acoustic mode, he asked the crowd if anyone had an E harmonica. You can hear what sounds like a dozen thud onstage.

To put it all in perspective, there is fascinating material on Hibbing, including a wall made of the iron ore that was the town’s reason for being; on the legendary songwriter Woody Guthrie, whom Dylan at first slavishly imitated; on key participants in the folk boom of the early 1960s; and on the civil rights and antiwar movements of that time.

All this context helps keep Dylan at human scale without in any way diminishing his accomplishments. But what really humanizes him for visitors, Emmons says, are the numerous highly personal artifacts scattered through the show.

“Bob Dylan’s American Journey” is a compact 3,000 square feet, but there’s way more to it than can be crammed into a newspaper story.

We haven’t even mentioned the annotated “Bringing It All Back Home” album cover, or the $10 Turkish tambourine that helped inspire the famous song (it belonged to well-known New York sideman Bruce Langhorne), or any number of other evocative Dylan artifacts and video moments.