A healthy rivalry

MILFORD, Conn. – This is Subway territory, a small waterfront city of 52,000 that’s home to the nation’s largest restaurant chain, a place where Subway funds the arts and schools and sends kids to summer camp.

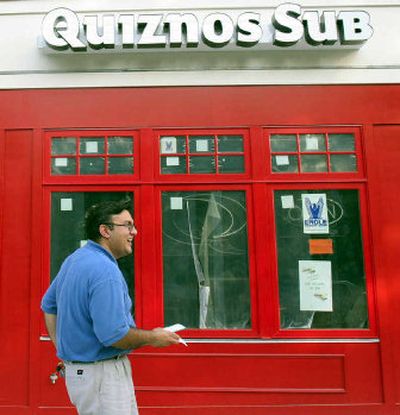

But just up the road from Subway’s headquarters, a developer recently erected seven white letters over an empty storefront: Quiznos.

“They’re challenging Subway,” observed resident Ernie Judson, gesturing to the newly painted red trim, “putting it right in their backyard.”

Consumers are noticing what restaurant industry analysts have seen for years. By making toasted sandwiches a hot item, Denver-based Quiznos has become the fastest-growing restaurant chain in the country, trailing only Subway as the nation’s No. 2 sandwich shop – not counting hamburgers.

After the upstart in the sandwich market hit the $1 billion sales mark last year, Subway took notice and launched is own brand of toasted sandwiches.

But industry analysts say Subway and Quiznos are locked in an unusual competition. Like McDonald’s and Burger King, they compete for the same market. But the sandwich purveyors also share a common goal: luring customers away from the burger joints.

Nowhere is that clearer than on Subway’s monthly sales charts, which frequently are unaffected even after a Quiznos opens nearby, said Fred DeLuca, Subway’s founder and president.

“How can that be?” he said. “Where did all the sandwich customers come from?”

The answer, he said, is that despite the presence of 18,000 Subway restaurants nationwide, the sandwich market remains underserved. Quiznos is bringing new customers to the market, which in turn benefits Subway.

Customer James Gore, who works in New Haven and was dining at a Quiznos on Monday, said he likes both chains.

“I thought about getting a burger, but I didn’t want to eat heavy and have to go back to work,” Gore said.

DeLuca even credits part of his company’s 11 percent average annual growth over the past three years to Quiznos’ emergence. “If they never existed, our overall growth probably would be slower,” he said.

Quiznos, too, benefits from the competition. Subway preaches the health benefits of sandwiches over hamburgers with an annual advertising budget that exceeds $100 million.

“The sandwich-segment boom is based on health-conscious people perceiving sandwiches as better for them than burgers or fried chicken,” said Dominick Voso, executive vice president of development for Quiznos.

Quiznos offers slightly more expensive food in larger, breezier shops. With nearly 4,000 stores, Quiznos executives say they’re blazing new ground, marketing the company as a higher-quality alternative to fast food.

But some see the Quiznos building blitz as a potential liability and say the company’s niche might not be big enough to support its growth.

Between 2002 and 2004, Quiznos leaped from 1,765 stores to 3,339. That’s an annual growth rate of nearly 45 percent, with company sales climbing 48 percent to $1.27 billion.

“I don’t think you could talk to any analyst in the country who would recommend that fast growth,” said Tom Miner, a restaurant consultant with Chicago-based Technomic Inc.

Growing makes sense when a new brand is hot, he said, but growing too fast leaves a company vulnerable to having too many stores if the novelty wears off.