Iran may be pushing Europe too far

ISFAHAN, Iran – Iran’s nuclear brinksmanship has paid off – so far.

It gained two years to complete uranium enrichment facilities during unproductive negotiations with the European Union, which has not carried out threats to seek U.N. sanctions.

An ultraconservative president was sworn into office Saturday, and hard-liners say they are determined to carry out the decision to reopen auranium conversion facility in Isfahan despite that threat.

But with the rejection Saturday of the EU’s latest proposal for averting a showdown, the government may be overplaying its hand.

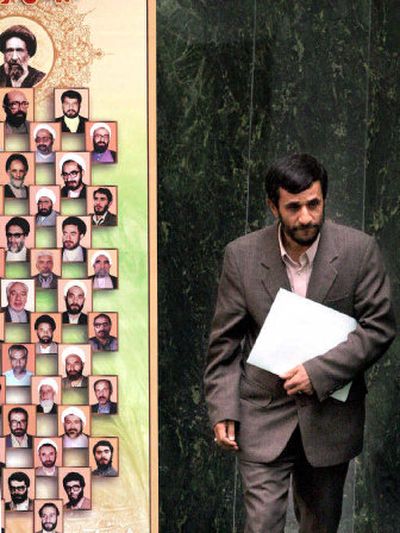

Both the United States and the EU warn that resumption of uranium conversion will prompt them to refer Iran to the U.N. Security Council for possible economic sanctions, which would deeply damage Iran’s already faltering economy – and new President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected largely on a promise to help the country’s poor. Indeed, Iran suspended uranium conversion eight months ago to avoid possible U.N. sanctions.

But the hard-line leadership touts the nuclear program as an example of Iran’s technical achievements, so backing down on continuing the program would be a blow to its credibility at home.

“It’s a serious confrontation,” Iranian political analyst Parviz Varjavand said. “The government has decided to challenge Europeans and America in the hope of getting concessions. It’s a high-risk policy they have adopted.”

Varjavand said the world will not see Ahmadinejad continue the moderate policy pursued by his predecessor. At his inauguration Saturday, the new president rejected pressure to change course.

The heart of the current faceoff is Iran’s vow to resume work in one part of its uranium development program within days, eroding the suspension of its nuclear program that has been the cornerstone of negotiations with the Europeans.

Ali Ansari, an associated fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs and lecturer on Iranian history at St. Andrews University in Scotland, said the chances of an agreement between the EU and Tehran are slim.

“There are red lines that neither side is willing to cross,” he said.

The United States is convinced the Iranians are seeking to develop weapons with their nuclear program, much of which was long kept secret from the U.N. monitoring agency.

Iran insists its program aims only to produce electricity. But the government also says it is a point of pride for Iran to have a domestic program for the entire nuclear cycle – from mining uranium, to processing it into fuel, to using it in a reactor.

For the West, the fear is that if Iran is allowed to develop nuclear fuel on its own, it also can secretly develop atomic bombs.

That is why the EU offered a long-term deal to provide nuclear fuel and other support for Iran’s electricity generation program in exchange for a formal commitment by the Tehran regime to give up operations that could be used to make weapons.

Iran says it rejected the EU proposal because it did not recognize Iran’s right – under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty – to enrich uranium.

The Iranians say they do not intend to restart enrichment yet, but will resume the conversion of raw uranium into gas used later to enrich uranium.

The result may be to unify the Americans and Europeans, whom Tehran previously has been able to play off against each other.

The showdown – and the question of whether either side will blink – now moves to the International Atomic Energy Agency, the U.N. watchdog agency that has called an emergency meeting Tuesday to discuss Iran’s stance.