You can take away the ‘alley,’ but you can’t change the lanes

Bowling alleys are the places that time forgot, places without hip-hop or double piercings, Tom Cruise or performance enhancing drugs. Windowless and air-conditioned, they don’t even acknowledge the weather outside.

Yet at Valley Bowl, 8005 E. Sprague, where Terri Brown hands out the shoes and turns on the lanes, somehow a bad case of modern-day social self-consciousness has set in. They’ve taken the alley out of bowling.

“We’re not called alleys anymore. We’re bowling centers,” said Brown. “The industry has been trying to change that for 10 or 15 years now. Because what do you think of when you hear alley? You think dirty. We’re not dirty.”

Dirty, no. But this is one slice of Americana that has never changed. This is where Nike didn’t “just do it.” In fact, Nike didn’t do it at all, despite racks upon racks of loud-colored, specialty shoes just waiting for a swoosh or Adidas triple stripe. Bowling doesn’t need flare.

On cue, Brown produces a pair of lace-up, crepe-soled, size 12 bowling shoes, half red, half blue. The way customers keep walking out the door with Valley Bowl’s rental shoes, Brown surmised the footwear must be somewhat hip.

She gives the inside of each shoe a blast of disinfectant, and they’re ready for the next guy. On the foot, the shoes are as pliable as an old first baseman’s glove. The same, broken-in feeling is available at bowling alleys anywhere. It is part of the familiarity that makes the experience easily navigable, comfortable.

Like so many cousins at a family reunion, bowling alleys are basically the same. The lane beds are always 39 boards wide, with a total lane width of between 41 and 42 inches. The distance from the head pin to the foul line where the ball is released is 60 feet. All 60 feet are thinly coated with oil so the balls practically float to the pins.

Lane six at Valley Bowl is the same as the lane on which 83-year-old Les Read bowled in Sioux City, S.D., 63 years ago as an Army enlistee bound for radio school. There, as a young soldier from Rhode Island, Read tried his hand at 10-pin bowling for the first time. He’d played a similar version of the game back East, except with a smaller, coconut-sized ball with much smaller finger holes aimed at just three pins. He selected a large ball with the same finger holes with which he was familiar and found out too late that there was indeed a difference between the two games.

“I went right down the lane with the ball and landed on my face,” Read says, laughing.

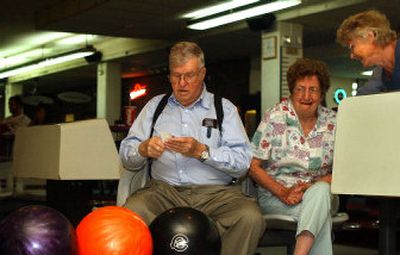

Today the ball swings only a short distance from the end of the Spokane Valley man’s arm like a tired pendulum in a wound-down clock. It rolls down the right edge of the lane for the first two-thirds of its journey before veering toward the center and making contact with the pins with a slow-speed crash. Read bowls every Tuesday with his wife, Muriel, and friends Robert and Marjorie Tupper of Post Falls.

Muriel Read releases a ball so slowly that it takes a full five seconds to reach the pins, which fall slowly like timber in the forest until a chain reaction has taken out all but three pins. She smiles at the suggestion that her score must be respectable.

“I don’t keep track,” Muriel Read says. Then, asked about her age, she responds, “I don’t keep track of that either.”

In the place that time forgot, amid the pounding tide of the ball and pins, a lot can be ignored.