In Death Valley it’s all desert, all the time

A few miles down the desolate strip that leads into California’s Death Valley National Park, visitors can drive up to an automated kiosk, dash from the car and buy a $10 park pass. Insert cash or a credit card into the machine and out pops your receipt, with the request that it be prominently displayed on the dashboard.

But when the words “Excessive Heat Warning!” are headlining the park’s daily report, prominently displaying anything on your dashboard proves folly. Within 30 minutes, the pass has been rendered useless. It has fried in the midday sun, its edges charred, its text blackened beyond recognition.

“Your pass burned up? Well, that’s how I know you paid,” says park ranger Vicki Wolfe, tittering as she hands over a map. “The only ones who complain about that are the ones who actually stuck it in their windshield.”

Lessons like that come quickly in this outpost of Hell, the hottest, driest, lowest spot in North America. Maybe the cruelest, too, but certainly not the loneliest.

Even during the height of the July and August scorchfest, when temperatures regularly top 113 degrees, tourists stream into the park, about 120 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

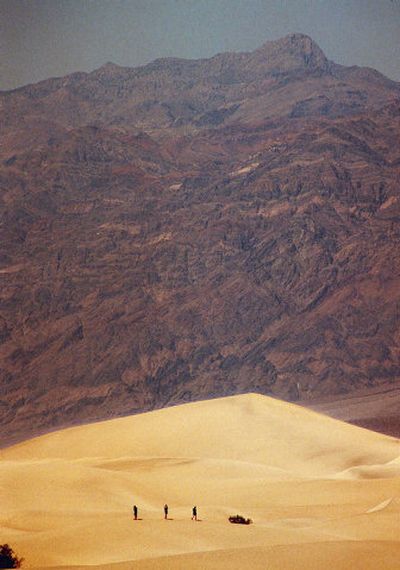

The majority come to simply experience the effects of triple digits on the psyche and to drive around snapping photos rather than strenuously hiking the arid canyons, mountains and dunes that make up the 3.3-million-acre park.

“We get a lot of Europeans this time of year,” notes Wolfe, explaining that while February through mid-April is Death Valley’s peak season, many foreigners enjoy the thrill of being in the desert Southwest at its nastiest.

Nasty it is, though in an exhilarating, what-the-heck-am-I-doing-here? kind of way.

The continent’s hottest temperature ever (134 degrees) was recorded July 10, 1913, at what is now Furnace Creek Ranch – a series of cowering motel buildings and cottages where most summer visitors are sequestered.

The tony Furnace Creek Inn, about a mile up the road, wisely closes for the summer.

On this day, the temperature hits 128, one degree off the record for the date. Two days later, the mercury will stretch to 129, a high for the year. Evidently, there’s not much difference.

“After 120 degrees, it’s all the same to me,” says park ranger Athena Siqueiros, who proclaims she’s used to weather extremes. “That’s when I feel it in my eyelids, which quiver in the heat.”

Eyelid-quivering heat indeed. If you’ve ever wondered what a Cornish game hen goes through in a convection oven, this is it. Waves of stultifying air bombard from every angle, with skin, hair and clothes hot to the touch in seconds.

Mouths reflectively open at the shock; ravens – or are they buzzards? – at Furnace Creek Ranch routinely circle the parking lot with beaks ajar. Walking at such sites as the Harmony Borax Works, a once-thriving mining operation, grows tiresome after a few minutes. Appetites wane.

The heat of Death Valley is an unwieldy byproduct of its otherworldly geography: a low, narrow basin framed by mountain ranges.

The sun blasts the desert floor, and the hot air rises. After it becomes trapped by the valley walls, it descends, only to be heated to an even greater extent.

The effects are far-ranging, and the learning curve can be painful.

Besides the general discomfort of sucking in superheated air, taking a picture leaves a welt if you touch the exposed metal on your camera. You can swim at the low-key (and entirely too sunny) pool at the ranch, but you sometimes must take your shoes off at water’s edge to avoid burning your feet.

Want something out of your car? Grab the wrong handle and you’ll realize you’ve been wheeling around in the equivalent of a solar flare on Firestones.

Oddly enough, no one seems to be complaining.

“What’s not to love?” enthuses Chris Morgan, of Lone Pine, Calif. “It’s my favorite park, there’s nothing else like it.”

He’s standing – and panting – in the Furnace Creek Visitor Center, which contains low-tech displays and killer air conditioning.

Morgan and friend Hollie McGill, of Ventura, Calif., got word of possible record-in-the-making temperatures and road-tripped 100 miles to be a part of it.

“I had to feel this for myself. After 115 degrees, it gets a little hard to handle,” says Morgan.

McGill looks as if she’s already had enough, but the two 32-year-olds jump back in the car and head about 18 miles south to Badwater Basin. At 282 feet below sea level, it’s the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere. It could also be the brightest.

Badwater is the site of a lake that evaporated thousands of years ago, leaving a layer of blinding white table salt stretching to the horizon; a pond remains, though in the summer months it’s an unimpressive if pungent puddle.

Park rangers advise visitors to stay close to the boardwalk at the salt flat’s edge, though few do. All should. After straying a couple of hundred feet onto the desert floor and becoming overwhelmed by the blistering glare, you’ll wish you were under the boardwalk.

Still, visiting the lowest point (a sign marking sea level is embedded on a nearby cliff) is a high point at Death Valley – even in the summer.

Geoff and Eunice Appleton, of Banbridge, Northern Ireland, are sniffing around Badwater about 5 p.m., the temperature still a disorienting 126.

The Appletons first visited the park 27 years ago and decided to return when they won two free tickets to the States. This time they took their children, Aaron, 15, and Kelli, 11.

“Ideally, we wouldn’t have come now, but this is when we had our holiday, and we’re not disappointed,” says Geoff, who seems to be enjoying himself – despite his wardrobe, which consists of long pants, a long-sleeve dress shirt, no hat.

When the rest of his family surrenders to the cooling confines of the rental, however, Geoff tromps off the boardwalk and onto the salt.

A few miles away, the enticingly named Devil’s Golf Course awaits. There’s an actual 18-hole course back at the ranch (to no one’s surprise, it’s duffer-free this afternoon), but you can’t play it from your car and, from all reports, Satan doesn’t frequent it.

After a jaw-rattling ride down a dirt road, cars come to a rest at the edge of a vast expanse of what appears to be salt pimples. The mounds, each a foot or so high, are all that remain from another lake, and the effect is mesmerizing.

Once outside the car and into the blast furnace, however, you can understand why Beelzebub would take to this area.

Nighttime brings little comfort to the Death Valley summer. Daily lows in July and August are 85 and above, though the high-90s are more common when the thermometer strains to its upper limits.

The window AC units in the Furnace Creek Ranch cottages – standard national park fare, with double beds, coffeemakers, TVs and small fridges – are working hard to keep rooms cool, but not hard enough. Fortunately, ceiling fans keep the warm air moving.

At 8:30 p.m., it’s still 111. About a dozen heads are poking out of the ranch pool, but the crowd is weirdly muted. It’s been a long, hot day, leading into a long, hot night.

Furnace Creek’s two restaurants, a steakhouse and a cafe serving diner-style food, are packed with the Euro-crowd, accustomed to eating later than the early-bird-special brigade.

Back at Badwater Basin, a nearly full moon is casting a surreal glow on the encroaching flats. The silence is complete. There are no coyotes howling into the night sky, no tourists puttering about. Soon the Death Valley air is alive, gushing fiercely as the desert floor begins to cool.

But it’s time to go. The eyelids have started to quiver.