Textbook ‘bundling’ costs students a bundle

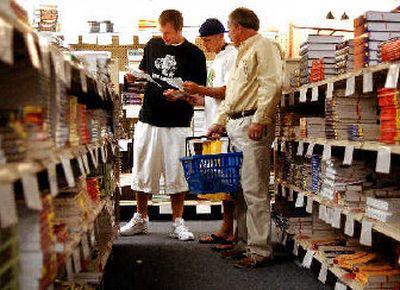

Garrett Swanburg, a freshman-to-be at Gonzaga University, dropped $400 on brand-new textbooks last week.

GU law student Demetre Christofilis says he spends $400 to $600 a semester on textbooks and has a hard time finding used ones.

Danielle Stewart, a senior nursing student at Washington State University-Spokane, studies in a particularly costly discipline – and one in which the textbooks are steadily being updated.

“I don’t think I’ve bought a used book since I’ve been in nursing school,” she said, “because they change all the time.”

It may seem like an eternal complaint on college campuses, but a new federal study says textbook prices have risen faster than average over the last 20 years, driven by rapidly changing editions and by the growth of “bundling” supplements with textbooks. Both thwart used-book sales, the report concludes.

The July 2005 report by the Government Accountability Office concludes that the average U.S. college student will spend about $900 a year on textbooks and supplies. It says textbook prices increased by 6 percent a year between 1986 and 2004, twice the rate of inflation overall.

“Wholesalers, retailers and others expressed concern that the proliferation of supplements and more frequent revisions might unnecessarily increase costs to students,” the report’s summary says.

Booksellers and students say it’s gotten harder to buy used textbooks at the bookstore – just as it has become easier to buy and sell them online. As a result, they say, publishers update books more frequently than necessary and bundle them with supplements, making it harder for campus bookstores to sell used books and making the used books available on the Web a sometimes-risky proposition for students.

“I think the efficiency in used books is driving the publishers to do things to compete against the used books,” said Scott Franz, textbook manager for the GU bookstore.

Textbook publishers have complained that the GAO report is biased against them and uses inaccurate figures to mark the increase in prices. Bruce Hildebrand, executive director of the Association of American Publishers, says textbook costs have not risen as fast as the GAO report concludes, and that by including “supplies” in the same category the report is burdening publishers with responsibility that isn’t theirs.

Katie Swanburg, a senior at University of Washington this year, was helping her brother, Garrett, buy books at the Gonzaga bookstore last Thursday. She said she typically tries to find used books for her classes, but that it can be risky to buy them online – only to find them outdated.

Still, “I try to find the used ones if I can,” she said.

‘A lot of bundles’

Textbooks are big and complicated business.

In academic year 2003-2004, students and their families spent more than $6 billion on new and used textbooks, according to the GAO report. The National Retail Federation estimates that textbook spending will reach nearly $12 billion this fall.

Unlike a more straightforward retail operation, the business of selling textbooks at campus bookstores is complicated: professors choose the books, tending to favor the most up-to-date texts; book stores try to predict class loads, order and sell books, and sometimes buy them back for resale; and publishers offer widely expanded add-ons that may come with a textbook, from online tutorials to self-tests to study guides.

“We sell a lot of bundles right now,” said Catherine Scott, director of college stores for the Community Colleges of Spokane.

At the GU bookstore last week, Franz offered three examples of bundling. One childhood education book was wrapped together with a new primer on changes in the law. An accounting book came with an additional study guide.

“That’s a great thing,” he said. “That’s a legitimate thing.”

But he also held up a textbook for a religion class. The book had no apparent additional material but was wrapped in plastic and given a different ISBN number – the number used by booksellers, retailers and others to track books.

When that book is unwrapped and the ISBN number on the wrapper is thrown away – leaving the original ISBN number printed on the book jacket – it essentially becomes a different book. When a student attempts to return it for resale, the store might refuse it even if was intending to buy back that text, Franz said.

“That’s the effect,” he said. “That’s not the intention, I don’t think.”

Scott agreed with the report and others who criticized book publishers for updating books with few changes – making last year’s text obsolete for no good reason.

“There’s a significant number of books that change editions that have no business changing editions,” she said.

The GAO report noted that for students at community colleges – “where low-income students are more likely to pursue a college degree program and tuition and fees are lower” – the cost of textbooks are a bigger burden.

The average community college student spends $866 a year on textbooks and supplies, about three-quarters of the cost of that student’s tuition and fees. For a full-time student at a four-year school, the average is nearly $900, or 26 percent of tuition and fees.

‘High-risk thing’

In 2004, the State Public Interest Research Groups released “Ripoff 101,” a blistering critique of textbook publishers that helped prompt the GAO report.

PIRG, which advocates for more affordable access to higher education, updated its report this year. It said that during the previous year, 59 percent of students the group surveyed said they couldn’t find a single used textbook for any class.

The report also said that publishers shouldn’t bundle products but sell the pieces individually. It cited several specific cases in which bundling drove up the prices of a textbook dramatically and showed that American students were paying more than 100 percent more for some textbooks than their British counterparts.

Prompted by congressional calls for investigation in the wake of the PIRG report, GAO undertook its study of publishing practices. Though the report said textbook prices have risen at twice the rate of inflation from 1986 to 2004, it noted that tuition and fees had increased even more.

Publishers told the GAO that instructors are driving the demand for more supplements and that frequent updates are needed to keep up with faculty.

The Association of American Publishers has objected strongly to some portions of the report, and it said the report appeared biased. In particular, the group said that the GAO estimate of an average student cost of $898 for textbooks and supplies is too high and unfairly lumps supplies in with books. The AAP suggested a different method of calculating the cost that arrived at an average cost of $580 for textbooks per full-time students, but the GAO did not adopt their figures.

In a letter attached to the report, the AAP also said the report seemed biased in favor of used book sales.

“We believe the editorial style of the draft report suggest GAO advocacy for used books and used booksellers rather than providing a factual analysis of the industries,” said the letter.

Hildebrand, the publishers association spokesman, said the report omitted information about several low-cost alternatives from publishers and that for the average student, textbooks represent just 6 percent of the cost of education and have increased about the same rate as inflation.

He also noted that student spending has been exploding in recent years – and not for school supplies, necessarily, but for cell phone bills and dorm design. Some of the criticism of publishers is driven by bookstores that have a vested interest in selling used books, because they have a larger profit margin.

“They prefer to sell used books because they make more money from them,” he said.

Franz said that used books may have a higher markup by percentage of price, but the actual dollar amount of the profit made on each book is typically similar to new books. It’s also risky to buy them back. If a bookstore can’t resell them – because an edition has changed or because it lacks a new supplement – they’re out the money.

“Once we have a book from a student, it’s ours,” he said. “It’s a high-risk thing.”

Franz said he does not blame publishers for problems with textbook sales, but he thinks that the various parties involved ought to figure out a way to make it work better for students.

In the meantime, for students like WSU-Spokane senior Nicole Hinkel, the ability to buy or sell used textbooks is catch-as-catch-can.

“It seems like every other year I can sell my books back,” she said.