‘Dolly the sheep’ researcher granted license to clone cells

LONDON – The scientist who attracted the world’s attention by cloning Dolly the Sheep is about to take another major step for medical research: cloning human embryos and extracting stem cells to unravel the mysteries of muscle-wasting illnesses like Lou Gehrig’s disease.

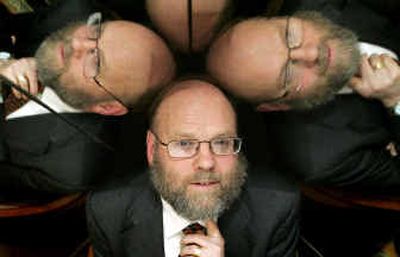

Ian Wilmut, who led the team that created Dolly at Scotland’s Roslin Institute in 1996, was granted a cloning license Tuesday by British regulators to study how nerve cells go awry to cause motor neuron diseases.

The experiments do not involve creating cloned babies, but the license has nonetheless stirred fresh controversy over the issue and prompted abortion foes and other biological conservatives to condemn the decision.

“Are we supposed to be appeased by Professor Wilmut’s declarations that the human embryos will be destroyed after experimentation and that his team has no intention of producing cloned babies?” asked Julia Millington of the London-based ProLife Alliance.

“All human cloning is intrinsically wrong and should be outlawed. However, the creation of cloned human embryos destined for experimentation and subsequent destruction is particularly abhorrent.”

Wilmut, speaking after the announcement in Edinburgh, Scotland, defended the move.

“We all take for granted the very much healthier life that we have now compared with people 100 years ago,” he said. “I think that the majority of people support this type of research and hope it will be successful in helping to bring useful treatment for diseases like motor neuron disease.”

The license is the second one approved since Britain became the first country to legalize research cloning in 2001. The first was granted in August to a team that hopes to use cloning to create insulin-producing cells for transplant into diabetics.

In the latest project, Wilmut and motor neuron expert Christopher Shaw of the Institute of Psychiatry in London plan to clone cells from patients with the disease, derive stem cells from the resulting embryo, make them develop into nerve cells and compare their evolution to that of cells derived from healthy embryos.

The cloning technique, called cell nuclear replacement, is the same as that used to create Dolly. It has already been applied to humans by scientists in South Korea, who created the clone to extract stem cells.

Dr. Brian Dickie, director of research at the London-based Motor Neuron Disease Association, said the experiments could revolutionize the future treatment of motor neuron disease, which afflicts about 350,000 people worldwide and kills about 100,000 people a year.

“It’s about 135 years since (motor neuron disease) was first characterized and here we are, more than a century later, and we still don’t know the cause of over 95 percent of cases. We haven’t got a diagnostic test for the disease and we’ve made very modest inroads in slowing the disease progression,” Dickie said.

“This opens up opportunities on three fronts: to understand how motor neurons become sick and die, to identify genetic causes of the disease and to rapidly screen new drugs,” he said.

The mechanism behind motor neuron disease is poorly understood because the nerves are inaccessible in the brain and central nervous system and can only be examined after the patient dies.

Motor neuron disease is an umbrella term for a collection of illnesses that all lead to loss of muscle function because of nerve failure. The most common is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease.