Emotions can break your heart, report says

Echoing the refrain of poets and country singers, doctors are reporting that strong emotional shock, such as the death of a loved one, can break your heart.

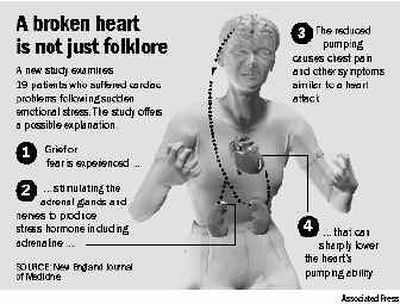

The researchers described for the first time the biochemistry associated with a little-known condition called stress cardiomyopathy, which causes temporary heart failure.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggests that many people believed to have suffered mild heart attacks may actually have experienced what the researchers dubbed “broken heart syndrome.”

The condition resembles a heart attack and can cause death. But it appears that most people recover without permanent damage.

An overwhelming number of victims are women, most in their 60s.

“There are going to be a lot of doctors and patients who say, in retrospect, what we were calling a heart attack may have been this,” said Dr. Ilan Wittstein, a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the study.

Wittstein and his colleagues found that the condition was typified by high levels of stress hormones known as catecholamines in the bloodstream.

These chemicals, which include adrenaline, can temporarily stun the heart.

The researchers looked at 19 cases of stress cardiomyopathy and found levels of the chemicals were two to three times above those found in actual heart attack victims, and seven to 34 times above those of healthy people.

Each of the subjects, who were screened in a hospital, had heart attack symptoms — chest pain and shortness of breath. Some had to be put on life support to keep their blood circulating.

All had experienced an emotional jolt. One woman watched her mother die at the hospital. Another had been in a car accident, but was otherwise unscathed. One woman was startled at a surprise birthday party.

Such stresses have been shown to trigger heart attacks in rare cases, but only in people who had coronary blockage and were predisposed to them.

These patients, however, did not have blocked arteries. Blood tests showed normal levels of the enzyme troponin, which is released when cells are damaged in a heart attack. All the patients recovered, some in just a few days. Magnetic resonance imaging of their hearts showed no permanent damage.

All but one of the cases they reviewed were women. About half the cases were triggered by the death of a family member.

For some patients, it was a relief that they had not suffered a heart attack. The earliest reference to stress cardiomyopathy was in a 1980 paper by a group of pathologists who had studied murder victims. Autopsies showed that they had not died of their wounds but from heart failure. Japanese doctors also reported several cases during the 1990s. Wittstein and Dr. Hunter Champion, also a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins, became interested in the syndrome in 1999 after noticing three women admitted in the same month with heart attack symptoms but whose hearts later showed no damage.

The researchers say the prevalence of “broken heart syndrome” remains unknown.

Dr. Scott Sharkey, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Foundation who co-authored another recent study describing stress cardiomyopathy, said he and his colleagues see cases each month – up to 3 percent of all older women who come to the emergency room with symptoms of a heart attack.

He said that the unmasking of the new condition would not immediately lead to changes in emergency rooms.

When time is of the essence, doctors still must assume the worst. People who come in with heart-attack-like pain will still undergo a coronary angiogram – an invasive procedure to detect blockages.