Leaks spur effort to ID aquifer threats

Prompted by the recent leaks at the BNSF Railway Co.’s Idaho refueling station, the Spokane Regional Health District’s board voted unanimously Thursday for a new effort to identify all sources of pollution over the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer.

The Board of Health vote came after a staff presentation that showed thousands of contamination sources over the aquifer in Spokane County, from septic tanks and old dry wells to a large Superfund cleanup site in Hillyard where petroleum has already been detected in the aquifer 150 feet below.

The region’s sole source of drinking water is still clean but there are growing indications of trouble, said Michael La Scuola of the regional health district.

“We are starting to see some trace elements (of contamination) in the aquifer. What’s protecting us so far is its sheer volume. We need to take a good, hard look at our older industrial areas,” La Scuola said.

Last Sunday, The Spokesman-Review reported on other BNSF contamination problems over the aquifer in Spokane County, including diesel spills along rail lines, contamination at the Parkwater rail yard in the Spokane Valley and major leaks below the North Market site in Hillyard, named a Superfund site in 1990.

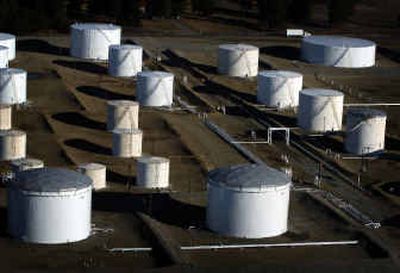

Besides the railroad, there are many other sources of pollution, including petroleum tank farms, 25,800 septic tanks in the “aquifer sensitive zone” and dozens of leaking underground storage tanks where petroleum products tainted soil, reached the aquifer and were swept miles away from the original sites where the leaks were detected, La Scuola said.

“There are an alarming number of known and suspected hazards over the aquifer. We need to identify them, secure the threats and have a response system in place,” La Scuola told the health board.

It is the board’s duty to protect the sole source of Spokane’s drinking water, said. Liberty Lake Councilman David Crump.

“I agree that water may become our most precious resource. A statement from this board may have some value,” Crump said.

Spokane County Commissioner Mark Richard asked how Spokane’s drinking water has been affected by the cluster of industries over the aquifer.

Tests of drinking water wells show an occasional “hit” that indicates the presence of solvents and other chemicals, La Scuola said. Many petroleum solvents float on top of the aquifer, but the public water supply is safe because the water is drawn from lower depths, he said.

However, chlorinated solvents such as trichloroethylene, a toxic chemical used in metal degreasing, are extremely soluble and can go deeper into the aquifer, La Scuola said. “We are starting to see trace amounts in parts per billion,” he added.

Richard offered a motion to show the board’s support for an effort to identify all contamination threats, review whether enforcement is adequate and establish ways to respond to future emergencies. Health district staff members were asked to report back on any regulatory loopholes and what role they could play with a modest use of their time.

Spokane County Commissioner Phil Harris voted for the motion, but not wholeheartedly. He said other regulators, including the Washington Department of Ecology and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, were already doing a good job protecting the aquifer.

“I’m seeing the bureaucracy of the health district growing … we just don’t need to be doing this,” Harris said.

Spokane Valley City Councilman Dick Denenny, the board’s chairman, said renewed concerns over the safety of the region’s drinking water arose from the recent BNSF spills. “The health district has an obligation to protect our drinking water,” Denenny said.

“I don’t want us to see mission creep, but this is an important issue,” Richard added.