Data: AIDS decline due to deaths, not chastity

BOSTON – Abstinence and sexual fidelity have played virtually no role in the much-heralded decline of AIDS rates in the most closely studied region of Uganda, two researchers told a gathering of AIDS scientists here.

Instead, it is the deaths of previously infected people, not dramatic change in human behavior, that is the main engine behind the ebbing of the overall rate, or prevalence, of AIDS in southern Uganda over the last decade, they reported.

The findings, not yet published, contradict earlier studies that attributed Uganda’s success in AIDS prevention largely to campaigns promoting abstinence and faithfulness to sex partners. Much of the prevention work in the Bush administration’s $15 billion global AIDS plan is built around those two themes, and Uganda is frequently cited as evidence that the strategy works.

If the report here stands up to scrutiny – and, more important, is borne out by surveys elsewhere in Uganda – it will deflate one of the few supposed triumphs to come out of AIDS-battered Africa in the last decade. The success of Uganda’s ABC strategy – the letters stand for Abstinence/Be faithful/use Condoms – has been widely touted, and is on the verge of being exported to its neighbors with the help of American money.

“There is an urgent need to assess abstinence and monogamy in other parts of Uganda,” said Maria Wawer, a physician at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health who presented the data at the 12th Retrovirus Conference.

Ironically, she and her colleagues found that the one practice whose use did increase between 1994 and 2003 was condoms – the part of the ABC triad that has been relatively de-emphasized in the Bush plan.

“Abstinence and monogamy are very good behaviors,” she said in a press briefing after her presentation. “On the other hand, the data support that in this setting, the behavior that seems to have been the easiest to increase over time is condom use.”

President Bush and administration officials have repeatedly cited Uganda’s experience in promoting their approach. “We can learn from the experience of other countries when it comes to a good program to prevent the spread of AIDS, like the nation of Uganda,” Bush said last June in Philadelphia, adding that the ABC program is “a practical, balanced and moral message.”

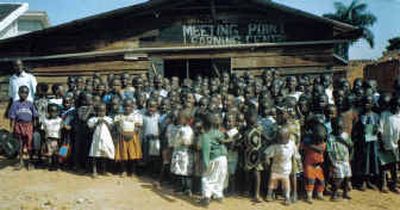

Wawer’s findings come from a study of 10,000 people ages 15 to 49 who live in 44 villages near Uganda’s border with Tanzania. Each year, researchers have gone door-to-door collecting blood and urine samples and asking about health and behavior. About 85 percent of residents cooperate with the study, which over the years has grown to include AIDS treatment and prevention services as well as research.

Today, the Rakai Health Sciences Program – which is run by Columbia, Johns Hopkins University and several Ugandan organizations – has about 400 employees. They include physicians, counselors and AIDS prevention educators.

Uganda is one of the 15 “target countries” in the Bush AIDS program, formally known as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

In the Rakai district, the percentage of women infected with HIV fell from 20 percent in 1994 to 13 percent in 2003. For men, that rate, or prevalence, of AIDS infection declined from 15 percent to 9 percent, roughly a decline of one-third.

Over that same period, however, the fraction of men reporting two or more sexual partners in the previous year rose from 28 percent to 35 percent. The fraction of young men ages 15 to 19 who were not sexually active fell from about 60 percent to just under 50. For women that age, the proportion not having sex remained at about 30 percent through the decade.

The median age of first intercourse for men fell from 17.1 to 16.2 years, and for women from 15.9 to 15.5 years, over the survey period.

Condom use, however, changed markedly. In 1994, only about 10 percent of the men said they consistently used condoms with non-marital partners, compared to 50 percent in 2003. For women of the same age, the rate of condom use in non-marital sex increased from 2 percent to 28 percent.

Earlier data indicating that Ugandans were delaying intercourse came from surveys of primary school students and health studies in 1989, 1995 and 2000 that were conducted in different regions each time.

Because the Rakai survey has continued for years in the same place, it provides an unusually precise measure of the rate of new infections, or incidence.

For women ages 15 to 24, incidence has risen slightly over the last decade, from just below 1.5 new infections per 100 women per year to just above. For men, incidence increased from about 0.7 infections to 1 per 100 men per year.

That means Rakai’s declining HIV prevalence is not due to a falloff in new infections. Instead, it appears to be explained by an increase in deaths. Between the 2002 and 2003 surveys, 125 people became infected, and 200 people with long-standing infections died.

“Death alone accounted for a 0.6 percent point reduction in HIV prevalence that year,” Wawer said.

Among her more troubling findings was that the percentage of men who had become infected in the previous year and also reported having two or more partners that year rose from about 48 percent to 68 percent. Newly infected people have unusually large amounts of AIDS virus in their blood and by some estimates are up to 10 times more likely to infect someone during intercourse.