Dozen soldiers taking the scenic route in Iraq

It turns out a dozen North Idaho soldiers in Iraq never made it to their camp for Christmas. And they may not be there yet.

Most of the 4,300 soldiers in the Idaho National Guard’s 116th Brigade Combat Team have begun “ride-along” training with troops they are replacing for Operation Iraqi Freedom III. Others in the brigade attended the dedication of a clinic in a village, played music at Christmas religious services and watched college football bowl games on big-screen TV.

Even as other soldiers establish some sense of normalcy, the lonesome dozen combat engineers and their three machine-gun equipped Humvees – or gun trucks as the soldiers call them – have been pinballing around Iraq as the security escort for a variety of military and commercial cargo convoys.

These last 12 soldiers from Charlie Company, part of the brigade’s combat engineers battalion based in armories at Post Falls and Bonners Ferry, had been left behind in Kuwait to escort a convoy north. The rest of the 116th either drove across Iraq to the northern city of Kirkuk, or flew there by mid-December.

In e-mails just before Christmas, these last 12 soldiers wrote that they were finally pulling out of Kuwait on Tuesday, Dec. 21, and hoped to be at their “home” base by Christmas Eve.

It seems they have gone everywhere but.

“Have about 15 min of computer time,” Sgt. 1st Class Kevin Kincheloe, 48, of Harrison, wrote in a hurried e-mail last week. “We stayed at Navistar (a camp on the Iraqi frontier) the 1st night, LSA (logistics support area) Scania the 2nd, Anaconda the 3rd, LSA Spiecher 4th, FOB (forward operations base) Summerall 5th, and we are currently back at Spiecher.

“We had six gun trucks in our serial all from different units. Everyone is getting shuffled around as they are scrambling to move equipment north,” Kincheloe wrote. “Haven’t talked to anyone in the unit since the 14th. They probably don’t even know where we are.”

The gun trucks were working with a National Guard transport company out of North Carolina, the 1450th, which has been running convoys for 10 months and has logged more than a million miles, Kincheloe wrote.

A Dec. 8 article in Stars and Stripes profiled a different transportation company, but offered a clear picture of the job: The 369th, the Reserve unit from Wichita, Kan., has collected numerous Purple Hearts. Two soldiers were wounded so seriously they were sent home, but there have been no fatalities, Stars and Stripes reported.

“We’ve all encountered small arms fire,” Sgt. 1st Class Larry Boudreau from West Virginia told Stars and Stripes. “I don’t think there’s a person in the company that hasn’t encountered an IED (improvised explosive device),” or roadside bomb.

More recently, insurgents have begun using car bombs – either detonated by remote control or driven into convoys by suicide bombers. These are known as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices, or VBIEDs.

“All you can hear is your heart,” 20-year-old Sgt. Tamara Holub, a driver from Wichita told Stars and Stripes about the moments after a roadside bomb explodes. “Everyday we go out the north gate [of Anaconda], we see the sign: ‘Is today the day?’ Every time you see that sign, you think about it.”

This sort of convoy duty was new to Kincheloe and the other North Idahoans. They provided security escort for “green convoys” (all military rigs) as well as “white convoys” of commercial trucks.

“Had IED and VBIED detonations on our route prior to our coming through,” Kincheloe wrote. “All I can say is wow! Wasn’t prepared for the sights, smells, sounds, people, traffic, etc. Incredible experience. Had some very close near misses with people and vehicles.”

The armored Humvees, especially the older model 1025 and 1026s, have sacrificed speed for safety. Even the new 1114s, built with a stouter engine and transmission to bear the extra weight of the armor plating, can ride like top-heavy turtles.

And the truckers, especially the commercial drivers who are often Turks, tend to stomp their feet to the floorboards and leave their security escort in the dust, believing they are safer with speed than with gun trucks.

“Yes, the truckers did punch it,” wrote Cpl. Steven Hanson, Bonners Ferry, the gunner in Kincheloe’s Humvee.

Kincheloe and Hanson noted their new gun truck, an 1114, broke down and was towed behind a truck – through Iraqi highway traffic – at speeds of better than 60 mph for two days before they could get some repairs in the city of Balad.

“It was a Christmas I will not forget. Christmas was cold standing up in the turret,” Hanson wrote.

Kincheloe noted, “It was a wild ride. One TCN (third country national) driver rear-ended a green truck. Had to leave the KBR (Halliburton subsidiary Kellogg, Brown and Root) truck behind. We think hodji(sic) got it because it was never recovered.”

Just as soldiers in Vietnam had Charlie, soldiers in Iraq refer to their foe – often invisible in the civilian population – as Hadji.

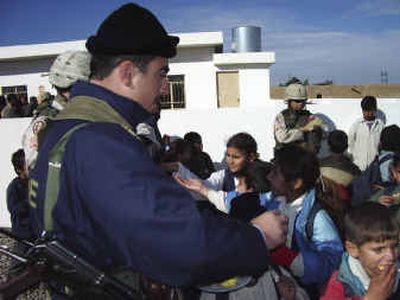

American soldiers also are told they are in the country to “win the hearts and minds” of civilians, and company commanders can tap into a discretionary fund for local improvement projects. A field artillery regiment based near the village of Allo Mahmoud near Kirkuk came up with $20,000 to help build a primary care health clinic in the village – home to both Kurds and Sunni Arabs. When staffed by Iraqi medical personnel, the clinic is expected to offer health care round-the-clock – a first for the village.

Lt. Col. Gordon Petrie, a public affairs officer with the 116th, e-mailed that officers in the brigade attended the dedication

“Every citizen of Allo Mahmoud will benefit from this health clinic,” Maj. Frank Batcha, the 116th’s Brigade Surgeon, told Petrie. “Its construction underscores the dedication of Kirkuk Province health care officials to improve primary health care throughout the region and how cooperation among different ethnic groups pays off.”

Last week medical staffers in the 116th paid a visit to the village of Lower Jawaala, 20 miles southwest of Kirkuk, to provide medications, checkups and dental care for Iraqis.

Col. Steve Knutzen, commander of the 116th Combat Engineer Battalion, which draws many of its soldiers from North Idaho, e-mailed to say the battalion will take over Operation Crayon, a program where hometown schools send supplies for kids in Iraqi schools.

And two of the soldiers in Charlie Company, 116 Engineers, Spc. Virgil Akers, Coeur d’Alene, and Spc. Dustan “Doc” Brown, Soda Springs, the company medic, provided music for the brigade’s first Christmas in Iraq.

“We had been volunteered to play for the X-mas Eve service at the chapel,” Akers, who plays fiddle, wrote in an e-mail. Thinking there was only one service, he and Brown (on guitar) rounded up three female backup singers and showed up early at the chapel to practice. They were surprised, Akers said, to find out “There were really three services. To make a long story short, we ended up playing/singing until 2400. Eight hours count-em eight!”

And last weekend, wrote Capt. Monte Hibbert, another brigade public affairs officer, about 200 of the 116th’s soldiers at the Kirkuk Air Base got to watch Boise State fall in the Liberty Bowl, which aired in the dining tent from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m., Kirkuk time.

But normalcy can be an illusion, as shown by this closing line from Kincheloe: “Have had incoming mortars at every stop – nothing close.”