Town under lethal cloud

GRANITEVILLE, S.C. – A lethal plume of chlorine leaking from a shattered rail tanker car kept 5,000 residents of this mill town away from their homes and forced officials to bring in repair crews a day after a pre-dawn train wreck and chemical spill killed eight people and sent scores to hospitals for treatment.

A rapid response by local emergency officials in the hours after two trains collided on Thursday morning helped evacuate hundreds of residents from a “hot zone” of contamination around the still-volatile wreck.

But officials continued to cordon off a mile radius around the now-deserted site, unable to staunch the flow of chlorine from one crushed rail car and worried about the possibility of leaks from two other cars loaded with toxic chemicals. A salvage crew prepared to apply a steel patch to the ruptured tank car and siphon off thousands of gallons of chemicals, but the work could last at least three days and as long as a week, officials acknowledged.

“We’ve not been able yet to get into the hot zone,” said Aiken County Coroner Tim Carlton, who confirmed Friday that autopsies performed on all eight of those who died after the collision showed they “suffered from chlorine inhalation.”

A 42-car freight train bound for Columbia, S.C. rammed into an idled locomotive early Thursday morning, toppling 17 rail cars and releasing a plume of poisonous chlorine that spread like dawn fog, overcoming dozens of workers from a nearby mill.

The freight train’s engineer, identified as Christopher Seeling, 28, of West Columbia, S.C., died in the crash, officials said. Panicked workers from the Avondale Mills textile plant rushed outside and several died on the spot, crumpling over into grass stained yellow by the chemical mist. More than 240 people sought hospital care for respiratory and other ailments. Most were later released. Emergency workers reported seeing carcasses of dogs and other animals. Chlorine also leached into a nearby creek, killing hundreds of fish, officials said.

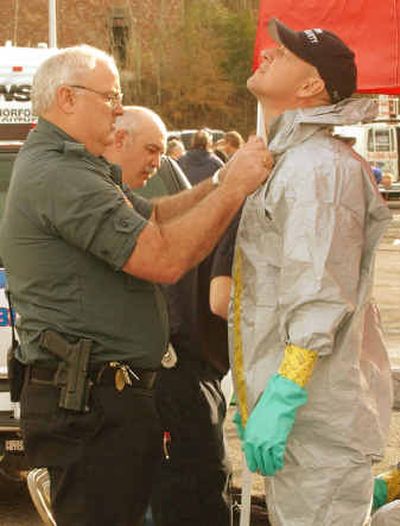

Local emergency officials said Friday that they were able to move quickly to the collision scene, aided by practice drills and heightened planning since the Sept. 11 terror attacks. But even with protective gear, three firefighters were overcome and one was in critical condition, officials said.

“I think it worked as well as we could have hoped,” said Greg Bailey, an exhausted shift manager for Aiken County Emergency Medical Services. Breathing from an oxygen tank and clad in a protective hazmat suit, he was one of the first to approach the wreckage.

But the chaos and unpredictable reactions of people unaware of the danger around them sometimes complicated the rescue work. Hours after the collision, gawkers strolled and drove up to the collision site until ordered out by police.

On Friday, Frank said that at least 12 holdouts inside the evacuation zone had refused to leave their homes. Officials were still trying to persuade them to leave and also were trying to track down at least one worker still not accounted for after the collision.

“I guess I should have stayed home,” said a chagrined Frank Norris, who walked into the toxic plume twice before he was driven out by a hacking cough and fits of vomiting. On Friday, he waited in a Red Cross shelter at the University of South Carolina campus, rubbing his eyes and worrying about his wife, who, complaining of chest pains, had been transported to a local hospital.

Norris, 49, an automobile mechanic who lives two blocks from the collision site, said he was working on a car in the rear yard of his house around 2:30 a.m. Thursday when a freight train rumbled by, heading south. About a minute later, he heard a series of booms. Norris peered down the track, but “couldn’t see a thing” in the dark.

The 42-car freight train – which included three tankers filled with liquid chlorine and two with other chemicals – rammed into another Norfolk Southern engine parked on a side track.

A typical rail tanker holds 180,000 pounds of chlorine. If released, the liquid forms a toxic cloud that can tail downwind as far as 40 miles. Testing near the collision site on Friday showed chlorine levels above those “considered a safe level,” but more distant readings showed lower levels.

Minutes after the wreck, workers inside the Avondale Mills plant nearest the crash site hurried to safety, only to rush directly into the poison mist. One worker, Carl Gartman, told the Augusta Chronicle that he saw a “yellow cloud coming at us.” Gartman said he made it out into the parking lot, but then “started coughing and spitting up all different kinds of stuff. I passed out.”

Later, emergency workers found several bodies around the plant, including one truck driver overcome in his cab.

Rhonda Keenan, 41, who works in Avondale Mills’ Townsend Plant, just up the road, said workers in her division continued working all night. “I didn’t think anything was wrong until later on when I noticed there was a funny taste in my mouth, a metallic taste.”

At home, she began coughing and had trouble breathing, and called an ambulance. Treated at St. Joseph Hospital, she later joined Norris and nearly 100 others staying overnight at the Red Cross shelter.

“The worst thing,” she said sadly, “is that I know everyone who died.”