Revival in Leadville?

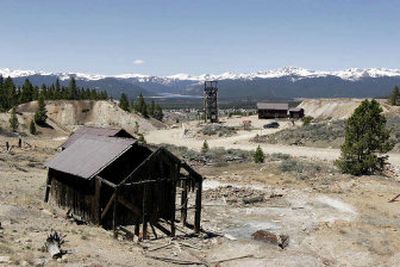

LEADVILLE, Colo. — A cold wind whistled down from the summit of 13,400-foot Bartlett Mountain, blowing dust past the earth-colored buildings that have stood silently over miles of empty tunnels for a generation.

The underground explosions, clanking trucks being loaded with ore and humming conveyor belts that defined the Climax Molybdenum Mine for 50 years are long gone, replaced by fences and cement road blocks.

The quiet could soon be over.

The mine’s owner, Phoenix-based Phelps Dodge, is considering starting up the open pit mine at Climax after watching the price of molybdenum — a mineral used to strengthen steel — skyrocket from $2 per pound in 2001 to $38 earlier this year.

“We are initiating a study on the possibility of reopening. We have not announced that we are reopening the mine,” Phelps Dodge spokesman Ken Vaughn said.

The study won’t be completed until late this year, but the prospect of reviving the signature business of this old mining town has created a buzz not seen in years.

Climax was once the world’s largest underground mine and employed about 3,200 people until the price of molybdenum plummeted in the 1980s. When the mine shut down in 1987, so did the town.

“We lost 80 percent of our property tax value, and we haven’t recovered,” Mayor Bud Elliott said in his office in the century-old City Hall building, glancing out at spectacular views of Colorado’s two highest peaks.

“We had the highest income per capita in the state. Now we’re one of the poorest counties in the state,” he said.

Colorado is among the highest producers of molybdenum, mining about 28 million pounds worth $350 million of the mineral last year, Colorado Mining Association president Stuart Sanderson said. Most came from the Henderson mine west of Denver, also owned by Phelps Dodge, which recently announced it was increasing production at the facility.

“The mineral industry, generally speaking, is experiencing a resurgence and prices that it has not seen in a decade or more,” said Roderick Eggert, director of the economics and business division at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden.

Eggert said the big issue mining companies face is trying to determine how long the boom will last.

Starting or restarting a mine can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, so companies look not only at current market prices but prices going back several decades. It is usually a history of ups and downs.

“I think it would be a mistake to think that these cycles are over, that prices are going to stay at their current high levels,” Eggert said. “They could stay here for several years but not indefinitely.”

Global demand for molybdenum has been pushed by construction and growth in countries such as China and India, said Luke Popevich, spokesman for the National Mining Association in Washington.

Leadville is no stranger to booms and busts, and its history is all about mining. Famed Titanic survivor Molly Brown (the “unsinkable”) was a poor Leadville resident until her husband stuck gold near town in 1893.

Doc Holliday had his final shootout at a saloon in Leadville in 1884 before heading for nearby Glenwood Springs to recuperate from tuberculosis.

By the turn of the century, when the area’s gold and silver industries slowed, molybdenum offered the next boom. Pushed by steel demands during World War I, Climax opened in April 1918.

Seven months later, when the war ended, the price of molybdenum crashed and the town went bust. More wartime production revived the mine — by the 1930s, Climax supplied 90 percent of the global demand for molybdenum, according to the geological survey.

Ken Chlouber, a former state lawmaker, worked at Climax until it closed.

“I absolutely loved it. My total responsibility was to make big rocks into little rocks, and I had this great big company buying me the largest firecrackers in the world,” Chlouber said.

Other miners were not as content. Turnover was high as miners and their families grew tired of working through cold, harsh Colorado winters in a town two miles above sea level.

“The town was wild and crazy. There were a lot of guys with a lot of money with nowhere to spend it,” said Rick Allison, 54, recalling his years working underground at Climax in the early 1980s. “There were a lot of big paychecks back then.”

Then came the next bust. Lake County’s property tax value was assessed at $240 million in the final months Climax was in operation, then fell to about $50 million when the mine closed.

“It was a huge double hit. Not only did everyone lose their jobs in town, there was a huge tax shift,” said Chlouber, who represented the area for 18 years in the state House and Senate.

He said the mine reopening would be a huge boost to the area.

“It would be the most exciting thing to happen in Leadville. We’ve tried everything to sustain our economy,” he said. “Mining is our past, it’s our future, and I hope it’s soon our present.”