NASA readies space probe to crash into speeding comet

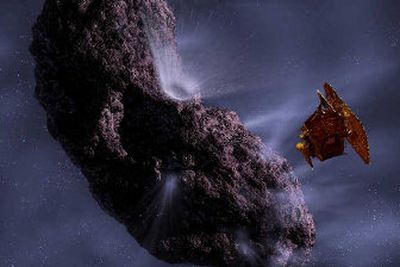

PASADENA, Calif. – It’s a space mission straight out of Hollywood – launch a spacecraft 268 million miles so it can aim a barrel-sized probe toward a speeding comet half the size of Manhattan and smash a hole in it.

But that’s what NASA expects its Deep Impact mission to do this weekend, with a goal of viewing the icy core of a comet that may hold cosmic clues to how the sun and planets formed.

It’s not without challenges. To ensure a bull’s-eye hit – and a spectacular Independence Day fireworks display in space – several things must happen just right.

Around 2 a.m. EDT today, the Deep Impact spacecraft must release the 820-pound copper “impactor” on course for a collision expected 24 hours later with the comet Tempel 1.

Scientists are confident they will be able to position the probe in the onrushing comet’s path, though that calls for precise maneuvers that the probe must execute without help from mission control. Once on auto-pilot, the probe has up to three chances before the collision to fire its thrusters to adjust its flight path for a direct strike.

“To hit the nucleus of a comet is a little bit like a baseball player trying to hit a knuckleball,” said Dave Spencer, mission manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, which is in charge of the $333 million project.

Late Saturday, the spacecraft made its final move to place the probe 500,000 miles from the comet.

“We’re right in the position where we expect to be,” said Monte Henderson of Boulder, Colo.-based Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp., which built Deep Impact.

Comets are blobs of ice and dust that orbit the sun and were born about 4.5 billion years ago – nearly the same time as the solar system itself. When a cloud of gas and dust condensed to form the sun and planets, comets formed from what was left over.

Scientists hope studying them will provide clues to how the solar system formed.

Tempel 1, their specimen, is a pickle-shaped comet that travels in an elliptical orbit between Mars and Jupiter.

After springing the probe, the mothership must slightly change course and stake out a prime seat 5,000 miles from the collision, which is expected around 1:52 a.m. EDT Monday.

The comet, hurtling through space at a relative speed of 23,000 mph, will run over the probe with energy similar to exploding nearly 5 tons of dynamite. A camera on the impactor will be shooting pictures as it heads toward its doom.

Little is known about comet anatomy, so it’s unclear what exactly will happen when Tempel 1 is hit. Scientists expect the collision to spray a cone-shaped plume of debris into space. The resulting crater could be anywhere from the size of a house to a football stadium, and be between two and 14 stories deep.

“We still don’t know what this comet holds in store for us,” said Rick Grammier, Deep Impact project manager.

Scientists will work feverishly to download data from the spacecraft before it makes its closest approach to the comet less than 15 minutes after impact. Their worry is that Deep Impact could be damaged by flying debris, risking the valuable data. A trio of space telescopes – the Hubble, Chandra X-ray Observatory and Spitzer Space Telescope – and dozens of ground observatories will also view the collision and aftermath.

So will amateur astronomers in the western United States and Latin America, who should be able to view the impact through their own telescopes. It will not be visible in the eastern United States and upper Midwest.

Launched in mid-January from Cape Canaveral, Fla., Deep Impact sent images of the comet’s nucleus for the first time last month from a distance of 20 million miles away.

It also witnessed two outbursts of ice from the comet – not a major concern to scientists who have plenty else to worry about.