Cleaning up the city

STOCKHOLM, Sweden – From catalytic converters to alternative fuels, the fight against big-city smog has for years been fought inside combustion engines and exhaust pipes.

Now, scientists are taking the fight to the streets by developing “smart” building materials designed to clean the air with a little help from the elements.

Using technology already available for self-cleaning windows and bathroom tiles, scientists hope to paint up cities with materials that dissolve and wash away pollutants when exposed to sun and rain.

“Among other things, we want to construct concrete walls that break down vehicle exhausts in road tunnels,” said Karin Pettersson, a spokeswoman for Swedish construction giant Skanska. “It is also possible to make pavings that clean the air in cities.”

The Stockholm-based company is part of a $1.7 million Swedish-Finnish project to develop catalytic cement and concrete products coated with titanium dioxide, a compound often used in white paint and toothpaste that can become highly reactive when exposed to ultraviolet light.

This is the idea: UV rays hitting the titanium dioxide trigger a catalytic reaction that destroys the molecules of pollutants, including nitrogen oxides, which are emitted in the burning of fossil fuels and create smog when combined with volatile organic compounds.

Exposure to high levels of nitrogen oxides can trigger serious respiratory problems, including lung damage.

The catalytic reaction also prevents bacteria and dirt from sticking to a surface, making them easily removed by a splash of water or rain.

Bo-Erik Eriksson, head of research at Cementa, another company participating in the Swedish-Finnish project, said the byproducts of the reaction, called photocatalysis, are benign, though it depends on what substances are involved: Organic compounds are broken down into carbon dioxide and water, while the nitrogen oxides yield nitrate salts.

Research in the field has been made possible by the revolution in nanotechnology – science dedicated to building materials from the molecular level. The catalytic properties of titanium dioxide become active when it is applied in a very thin layer, or in microscopic particles.

A range of self-cleaning products coated with titanium dioxide, including windows and ceramic tiles, are already on the market, but the focus has mostly been on their practical value rather than the environmental impact.

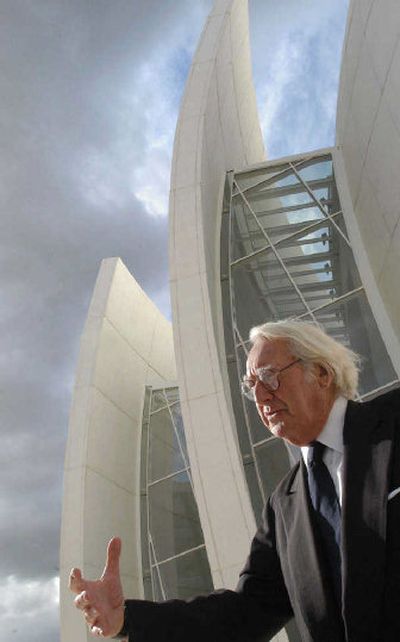

In Rome, the Dives in Misericordia church, designed by U.S.-based architect Richard Meier, is made of self-cleaning concrete that helps keep the surface shiny white. In Japan, several modern buildings including the Marunouchi Building in downtown Tokyo, are covered with photocatalytic tiles to reduce discoloring from pollution.

“Now we have to change and think of the product not just for architectural purposes, but also for environmental purposes,” said Francesco Galimberti, spokesman for Italcementi, maker of the concrete for the church in Rome.

In a test in 2003, the company coated 75,000 square feet of road surface on the outskirts of Milan with photocatalytic cement. It found nitrogen oxide levels were reduced by up to 60 percent, depending on weather conditions.

A similar experiment in France found nitrogen oxide levels were 20 percent to 80 percent lower in a wall plastered with photocatalytic cement than one with regular cement.

Encouraged by such results, the European Union last year earmarked $2.27 billion for a project to develop “smart” construction materials that would break down nitrogen oxides and other toxic substances, such as benzene.

However, researchers admit they’re still not sure how much of an impact the technology could have on air pollution outside of controlled test environments.

“Now we want to find out if it works optimally and economically and make sure it has a long-lived effect that does not disappear after a couple of years,” said Eriksson of Cementa.

Cost is another issue. Galimberti said Italcementi’s products are 30 percent to 40 percent more expensive than regular concrete, and using the external air quality as a selling point doesn’t necessarily appeal to builders with tight budgets. The company’s sales pitch is that self-cleaning materials will save money in the long run.