Physicist’s spiritual work honored

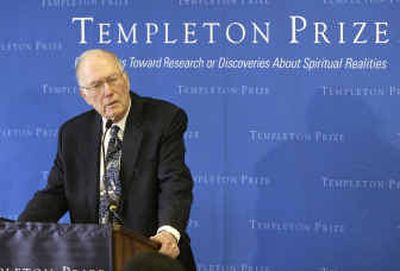

Charles Townes, the University of California, Berkeley, professor who shared the Nobel Prize in physics in 1964 for his work in quantum electronics and then startled the scientific world by suggesting that religion and science were converging, was awarded the $1.5 million Templeton Prize for progress in spiritual knowledge Wednesday.

The prize, the proceeds of which Townes plans to largely donate to academic and religious institutions, recognized his groundbreaking and controversial leadership in the mid-1960s in bridging science and religion.

The co-inventor of the laser, Townes, 89, said no greater question faced humankind than discovering the purpose and meaning of life – and why there is something rather than nothing in the cosmos.

“If you look at what religion is all about, it’s trying to understand the purpose and meaning of our universe. Science tries to understand function and structures. If there is any meaning, structure will have a lot to do with any meaning,” he said in a telephone interview from New York. “In the long run they must come together.”

Townes said that it was “extremely unlikely” that the laws of physics that led to life on Earth were accidental.

Some scientists, he conceded, have suggested that if there are an almost infinite number of universes, each with different laws, one of them was bound by chance to hit upon the right combination to support life. “I think one has to consider that seriously,” Townes told the Los Angeles Times. But he said such an assumption could not presently be tested. Even if there are a multitude of universes, he said, we do not know why the laws of physics would vary from one universe to another.

Townes said that science is increasingly discovering how special our universe is, raising questions as to whether it was planned. To raise such a question is the work of scientists and theologians alike, said Townes, who grew up in a Baptist household that embraced “an open-minded approach” to biblical interpretation.

In 1964, while a professor at Columbia University, Townes delivered a talk at New York’s famed Riverside Church that became the basis for an article, “The Convergence of Science and Religion,” which put him at odds with some scientists. In the article, Townes said science and religion should find common ground, noting “their differences are largely superficial, and … the two become almost indistinguishable if we look at the real nature of each.”

In a 1996 interview with the Times, Townes said that new findings in astronomy had opened people’s minds to religion. Before the 1960s, the Big Bang was just an idea that was hotly debated. Today, there is so much evidence supporting the idea that most cosmologists take it for granted.

“The fact that the universe had a beginning is a very striking thing,” Townes said at the time. “How do you explain that unique event (without God)?”

Townes this week spoke of his interest in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. The sheer number of stars and planets, he said, would likely increase the probability of intelligent life elsewhere. But for life to get started on even one planet is “highly improbable. It might not have started more than two or three times,” he said. “It would be fascinating to find somebody out there.”

Born in Greenville, S.C., in 1915, Townes received a bachelor’s degree in physics summa cum laude from Furman University in Greenville when he was 19. Two years later he received a master’s in physics from Duke University, and in 1939 received a Ph.D. in physics from the California Institute of Technology with a thesis on isotope separation and nuclear spins.

During World War II, he helped develop radar systems that functioned in the humid conditions of the South Pacific.

His research led to development of the maser in 1954, which amplifies electromagnetic waves. He later co-invented the laser. His work for which he shared the 1964 Nobel in physics led to a variety of inventions and discoveries in medicine, telecommunications, electronics, computers and other areas.

He was named provost and professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1961, director of the Enrico Fermi International School of Physics in 1963, and, in 1967, university professor of physics at the University of California at Berkeley, a post he held until 1986.

The prize will be presented to Townes in a private ceremony by the duke of Edinburgh at Buckingham Palace next month.