Legal community rallying around disciplined lawyer

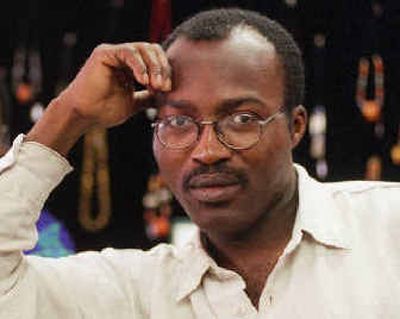

A lawyer in trouble usually commands about as much sympathy as a fly in a punch bowl. Uche Umuolo is different.

His law license has been suspended for two years because he mishandled $550 in trust money, but Spokane judges and attorneys are rallying around Umuolo.

They say he has a heart of gold and hope the state Supreme Court will give him a break. On Monday, attorney Bob Dunn helped the Nigerian-born Umuolo file a formal petition for reconsideration, based in part on cultural differences.

Dunn cited the advice he himself received from established lawyers when he began his practice and said Umuolo didn’t receive that kind of support. He volunteered to serve as Umuolo’s mentor.

“Based on my belief in the inherent goodness of this young lawyer, I do not think it is a stretch to say that the system let him down,” Dunn wrote in a statement of support. “… As a ‘village,’ we, the bar, did an unacceptable job.”

Umuolo is a competent lawyer who struggles with English and lacks business skills, Dunn wrote.

“The problem is he is so much into helping, especially the black community, that he really can’t perform the cases he does,” said Umuolo’s friend Francis Adewale, an assistant Spokane municipal public defender.

Umuolo has been honored by the Spokane County Bar Association for his work in the association’s Volunteer Lawyers Program for indigent clients.

“He was constantly giving,” program coordinator Kellee Spangenberg said. “He never turned us down, ever.”

Efforts to reach Umuolo for comment were unsuccessful. Friends said he is in Arizona, looking for work.

In a statement filed with the petition for reconsideration, the 41-year-old Umuolo describes a litany of hardship and perseverance that shaped him. He said he was 10 years old before he saw a shower that worked.

Umuolo said he was the son of an uneducated man who saw education as the way for his children to escape poverty.

Eventually, Umuolo said, his father got a job with an American oil company and sent him to college in Arizona in 1982. A year later, Umuolo’s father lost his job and Umuolo had to drop out of school.

Umuolo said he worked three menial jobs to support his wife and first son and to save enough money to resume his education. He passed the Washington bar examination in 1995 after earning his law degree in Arizona.

His goal was to make his father’s dream a reality, and he is now responsible for helping support his parents and 22 other relatives, Umuolo wrote.

Gerry Alexander, chief justice of the Washington Supreme Court, cited major obstacles to reconsideration of Umuolo’s suspension, including a lapsed deadline. But he didn’t rule out the possibility.

Alexander found Umuolo’s suspension appropriate, but said the support Umuolo has received is “unprecedented.” In 10 years on the Supreme Court, Alexander has seen no other case in which judges have come to the support of a disciplined lawyer.

Spokane County Superior Court Judge Neal Rielly views Umuolo’s suspension Dec. 16 as a blow to poor people’s access to justice.

Rielly is among a dozen Superior Court judges and commissioners who signed a petition asking the state Supreme Court to reconsider its suspension of Umuolo’s license. Rielly also is one of two longtime Superior Court judges who took the highly unusual step of writing unsolicited testimonial letters on Umuolo’s behalf – something neither had done before.

“That is more than remarkable,” Spokane attorney Pat Stiley said. “I’ve been practicing for 30-some years, and I’ve never seen anything like that.”

But Umuolo “is that kind of human being,” Stiley added.

“Mr. Umuolo has a heart of gold,” Rielly wrote.

“Of all the attorneys I have seen get in trouble over the years, I can’t think of another one I would have written that letter for,” Rielly added in an interview.

Judge Robert Austin, the other letter writer, said one of Umuolo’s clients came to him in tears because Umuolo’s suspension left her without a lawyer.

“Mr. Umuolo does not rank as one of the top lawyers who have ever appeared before me, based on legal ability,” Austin wrote. “He does rank, however, as the highest lawyer based on passion, justice of the cause and ardent advocacy for his clients.”

Austin said Umuolo represents many people free of charge and takes on cases some attorneys would consider unwinnable.

“Even in those cases, he has made me think, appealed to my sense of justice, and supported it with the law,” Austin said.

Both Austin and Rielly said they believe Umuolo has behaved ethically and honestly in their courts.

Violated accounting rule

Rielly and Austin were careful not to defend the conduct that got Umuolo in trouble. He clearly violated an important rule that requires strict separation and accounting of clients’ money.

Austin said, however, that he thinks the two-year suspension is “unusually harsh” for a violation the state bar association acknowledged may not have been deliberate.

At issue is a $550 balance on money Umuolo was holding in trust for a client who died. Until he was challenged, Umuolo kept the money instead of giving it to the person entitled to receive it.

Attorneys who know Umuolo say they’re convinced he is guilty only of bad bookkeeping. A man who can’t say no to a penniless client is an unlikely thief, they say.

“I’m having a real tough time believing it has anything to do with greed for making money or taking advantage of clients in a monetary sense,” attorney Dunn said.

Attorney Adewale said most of Umuolo’s clients are “the people in between,” too poor to afford a private attorney but not poor enough for a public defender. Most are from Spokane’s black community.

“He had his arms full pursuing these cases that no one wants to take because there is no money in it,” Adewale said. “When they can pay, it is pecans.”

The good thing about it, Adewale said, is that clients don’t forget Umuolo.

“The mark he made on their lives is indelible,” Adewale said. “He has helped them get their kids out of drugs, into schools; helped them get their kids out of the criminal justice system, out of the streets, into homes, into the better things of life.”

Spokane resident Sandy Baldwin retained Umuolo to help her teenage daughter and said he “gave her much needed advice and moral support.” In the course of that representation, Baldwin said, Umuolo offered to help the family resolve other legal problems.

“I was unemployed at the time and was unable to proceed with my divorce,” Baldwin said. “Mr. Umuolo represented me free of charge and negotiated a settlement and parenting plan that was beneficial to my sons and me.”

Cultural gap

Several of Umuolo’s supporters echoed Dunn in wondering whether cultural differences, perhaps a more casual attitude about money and paperwork, may have contributed to his financial transgression and his willingness to accept such harsh punishment.Stiley worked with Umuolo on a complicated workers’ compensation case involving Boeing employees who alleged discrimination against people with disabilities.

“There is a cultural gap there, and there have been times when I have wondered whether Uche was on the same page I was in terms of how to do something in our legal system,” Stiley said.

But, he added, he has seen Umuolo devote “extraordinary energy and passion to cases, enough to make me ashamed of myself for not putting in the same dedication to a client that he has.”

Attorney Dunn said he got to know Umuolo last fall when he began helping Umuolo with a “very, very tough” disability-discrimination lawsuit against Boeing, a companion to the case involving Stiley. Umuolo had taken on three clients who couldn’t afford to pay for a case that went to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals before returning to Spokane County Superior Court.

Without enough paying clients, Umuolo was unable to hire a professional officer manager, supporters say. He maintained his own trust accounts, improperly mixing his own money with his clients’ money.

Umuolo’s settlement with the bar association acknowledges that he “had only a marginal understanding of trust accounting” and incorrectly believed he was supposed to put all office receipts in his trust accounts. He kept no check registers and relied on memory to keep track of clients’ money.

“I’m not sure that he had an appreciation for how serious it was to make sure all the nickels were accounted for in a specific and certain fashion,” Dunn said.

Friends reach out

State bar association spokeswoman Judy Berrett said the requirement to keep clients’ money completely separate is important not only to prevent misappropriation but to protect the money from the clients’ creditors.

Putting personal and office money into a trust account as Umuolo did could compromise the trust account and expose clients’ money to creditors, Berrett said.

With Umuolo himself now at risk, a number of lawyers have been quietly passing the hat to help keep creditors away from his door.

“There are many of us in this community who want to make sure that this suspension does not devastate him,” Stiley said.