An endless debate

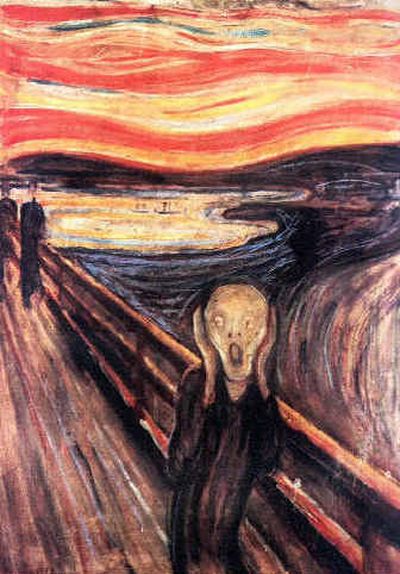

OSLO, Norway – Edvard Munch’s masterpiece, “The Scream,” has become a world icon of human anxiety, appearing on everything from popular T-shirts to blowup dolls – and causing endless debate among art experts.

What exactly is the surreal figure doing in the painting, with hands pressed to its head and open mouth: Screaming, or hearing a scream?

Interest has been stimulated in the Norwegian master’s works with the recent theft of three more Munchs in Norway, seven months after “The Scream” and another masterpiece, “Madonna,” were stolen from an Oslo museum.

The latest works, a watercolor and two prints, were recovered by police Monday, less than a day after they were stolen. Five young suspects are being held in jail pending indictment and trial.

A version of “The Scream,” as well as “Madonna,” were taken by gunmen from the Munch Museum in Oslo in August and have yet to be recovered.

There are four versions of “The Scream,” one of the world’s most recognized painted images, which shows an anguished figure against a surrealistic, reddish sky.

The stolen version was painted in 1893 as part of Munch’s “Frieze of Life” series in which sickness, death, anxiety and love are central themes.

The painter, who died in 1944 at age 81, could not have envisioned the popularity of the haunted figure that has appeared on clothes, inflatable figures and even dinner plates. Opponents of the re-election of U.S. President George W. Bush in the 2004 presidential campaign used it on T-shirts, with the words “Bush Again?”

Most believe the icon of anxiety is screaming.

Or is it? It could just as well be listening to a scream.

In his own writings about the painting, Munch said he was walking with friends when the sky turned blood red: “I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

Morten Zondag, a Munch expert with Blomqvist art house and auctioneers in Oslo, says that seems to make sense.

“If you look at the texts, you see it is a scream from nature,” he says. “I would think it portrays a scream from nature, but that this person or thing is a personification of that scream.”

Gunnar Soerensen, director of the Munch Museum in Oslo, is less certain.

“It could be a scream in nature or a person screaming,” he says. “It is a question of interpretation.”

Soerensen says experts know the place in Oslo that provided the backdrop for the painting, and there was certainly screaming there at the time: the bellows from a nearby slaughterhouse or the cries of patients at a psychiatric asylum, or both.

“The point is that he managed to paint a sound,” Soerensen says. “It is about a modern person’s anxiety.”

Munch worked in Germany as well as his native Norway, and his emotionally charged style was of great importance in the birth of the 20th-century expressionist movement.

“Everyone sees it in their own way, and that causes debate. I think that was part of the point,” says Hans-Martin Frydenberg Flaaten, whose University of Oslo thesis was on “The Scream.”

Flaaten says the figure’s hands do appear to be covering its ears, shielding them from a scream. However, it could also be clutching its head, a classic gesture of a scream.

Like Zondag, Flaaten sees it mostly as a scream in nature, with the figure personifying the scream. He believes the important thing is that Munch was trying to paint a sound, an idea that fascinated his circle of artists and writers, who also tried to find ways to hear colors.

The artist could have been inspired by many sights and sounds, which he combined into one painting, Soerensen says.

“It is shockingly easy to understand,” he says. “Is he screaming, or is he hearing a scream? Does it matter?”