Kinder and gentler

There’s no need to worry about any comparisons to Mother Teresa just yet. But one has to admit: Since Martha Stewart emerged from her five-month sojourn behind bars, there has been a change in the billionaire’s famously aloof demeanor.

The new version dispenses smiles and hugs with abandon, is refocusing her magazine on the emotional “whys” of homemaking and rails passionately against mandatory-minimum prison sentences.

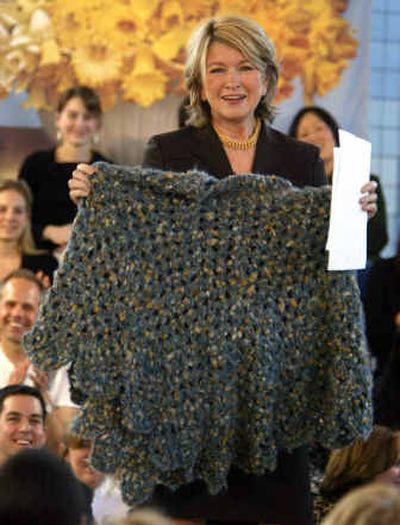

Mostly, she’s just uncharacteristically cuddly, from her prison-made poncho to her emotional hellos.

“All of you are my heroes,” Stewart said in her post-release meeting with Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia staff, as she blew kisses to the cheering crowd.

Pals say the domestic doyenne’s change is rooted in a newfound appreciation for what Leona Helmsley once disparagingly called “the little people.”

“Martha listened to the women around her as they shared their stories,” says Margaret Roach, Stewart’s friend and editor of Martha Stewart Living magazine.

“It was that connection and conversation with the other women that prompted Martha to talk about the ‘whys’ of what we do in (the magazine),” Roach says. “It’s not the pie you bake, per se, but the experience.”

Another friend agrees that Stewart has a renewed sense of purpose.

“Martha seems stronger than ever and has more time for human dialogue than ever before,” says New York art dealer Richard Feigen, who has known Stewart for 18 years.

“I don’t think this is a temporary thing,” he says. “The experience she had (in prison) has affected her personally, but it will also help her business. For five months, she had talks with people who are really potential customers.”

Which cuts to the heart of the matter: Is Stewart genuine or is this a public relations ploy?

For some famous white-collar criminals, prison genuinely was a springboard to a new calling. Take Watergate felon Chuck Colson, who found religion and now runs Prison Fellowship Ministries.

Another name that comes to mind is Michael Milken, who served time in the early ‘90s for securities fraud and is now renowned as a leader in the fight against prostate cancer. But his office is quick to blast the notion of a similarity, noting that Milken was a philanthropist before his legal woes.

“Some of the stories about Stewart cynically suggest that she ‘follow a strategy’ similar to Mike Milken’s,” says senior adviser Geoffrey Moore. “That’s an insult to the hundreds of people in Mike’s various philanthropies who have worked side-by-side with him, many for decades, to help him implement his lifelong passion for public service.”

In the 63-year-old Stewart’s case, there’s little doubt that a transformation of some kind has taken place.

Last July, she told Barbara Walters that while her hearth-and-home creations were unfailingly warm and fuzzy, she wasn’t.

“I just wish I were bubbly and happy and saying ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you’ (to employees) all the time,” she said.

Walters pressed. “Can you be that way?”

“I don’t think so,” Stewart replied.

Fast forward to mere weeks ago, when during an online chat with fans Stewart emphasized her upbeat nature (“Thank you very much for realizing I’m a positive, upbeat person,” she wrote one admirer) and asked them personal questions (“My confirmation name is Grace,” she wrote another. “What’s your daughter’s first name?”).

In the end, time will provide the best test of Stewart’s makeover.

“Keep an eye out in six months to a year, which is when she may think, ‘OK, I’ve given back, enough now,’ ” says David Zlotnick, law professor at Roger Williams University and an adviser to Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

Zlotnick says Stewart is following a familiar pattern. White-collar prisoners typically form fierce bonds with inmates, he says, “partly due to a strong fear of physical harm.”

There’s also the impact of meeting people whose lives are radically different from one’s own, which can be inspiring. But depression can loom ahead.

“She’s on a high right now, everyone is thrilled to have her back,” says Zlotnick. “But that can fade, and the reality of being a convicted felon sets in.”

If Stewart’s newfound humanism remains on display, it will vindicate supporters and may bring back former fans, women such as Michelle Nelson, a stay-at-home mom from Elmsford, N.Y., who stopped buying Stewart’s products when news of her scandal broke.

“I remember thinking, ‘Here’s another big shot trying to get away with something that the rest of us can’t,’ ” says Nelson, 32. “But if she can keep herself in this favorable light, I could well change my opinion.”

Still others are waiting to hear something far simpler from Stewart: an apology.

“If she’d only say, ‘I’m a lying felon,’ I could move on,” says Shawn Auer, 31, a sociology student at the University of Colorado at Boulder who recently started the Stewart-skewering realmartha.com Web site.

“Otherwise, she’s capitalizing on all this, and that just makes a mockery of our judicial system.”