Change flows with the river

Pedicure thrones at Zi Spa reflect the changing nature of Coeur d’Alene.

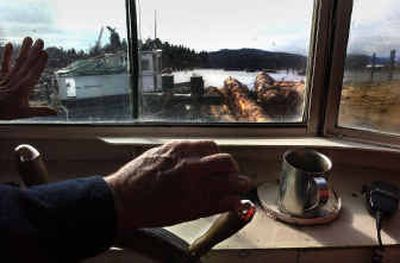

Tuscan Bella foot treatments cost $55 at the new spa overlooking the Spokane River. But customers who lounge on the leather recliners, their feet in jetted tubs, can still see parts of the city’s past. The spa’s third-story windows frame a distant log yard. A train rumbles by every morning en route to a nearby sawmill.

Developers are carving a new Coeur d’Alene out of the city’s blue-collar roots.

Once, this spot on the river housed Northwest Timber, a sawmill with a steam whistle that shrilled four times daily at shift change. The mill was part of Coeur d’Alene’s industrial waterfront, where tugboats, railroads and millworkers intersected in a common pursuit – turning trees from North Idaho’s forests into valuable export lumber.

Now the former Northwest Timber site is the epicenter of residential and commercial redevelopment sweeping along a five-mile stretch of the Spokane River.

Six years ago, Spokane developer John Stone bought the vacant mill site for about $6 million. The first office building looked a bit lonely and stark on the 70-plus acres.

These days, however, Stone’s office – adjacent to Zi Spa – overlooks millions of dollars worth of construction activity. A 14-screen theater is going up to the north. More office buildings are rising to the south. Condos and shops are in the planning stage. Eventually, planners expect 2,000 people will live on the old mill site and an adjacent gravel pit. Another 1,500 are expected to work there.

A few miles downriver, on a former Crown Pacific mill site, families are moving into million-dollar homes at Mill River, another developer’s project. The first phase sold out in four months. The second phase hits the market this summer.

Like the mill owners before her, Zi Spa owner Tammy Schneider spied economic opportunity on the waterfront. “I’m in the middle of a gold mine, I really am,” she said.

Schneider opened the 6,000-square-foot spa last summer, after a five-year stint as the Coeur d’Alene Resort’s spa director. The city was ready for a luxury spa catering to local residents, she figured.

In Zi Spa’s gift shop, bottles of facial moisturizers sell for $60. A 2½-hour body wrap, facial and foot massage runs $190. Business, said Schneider, has exceeded her expectations. The spa’s 40 employees anticipate even more customers after condos are built nearby.

Timber’s time is limited

For now, the riverfront remains a landscape of contrasts.

Less than a mile from the spa, the corrugated metal walls of the DeArmond mill enclose a world of hard hats, steel-toed boots and heavy equipment. Business activity here is measured in board feet. Workers take pride in the mill’s reputation for high-quality framing lumber.

“When you go to Home Depot in Coeur d’Alene, you’re buying a Stimson stud,” said Kevin Collins, plant manager. “The nicest looking studs are ours.”

But the last vestige of timber activity on the Spokane River could disappear within two years.

Developer Marshall Chesrown has a working agreement to buy the DeArmond and nearby Atlas mills from Stimson Lumber Co. The move would open up an additional 80 acres of waterfront for development, including an expansion of North Idaho College’s campus.

As part of the deal, Chesrown would build a state-of-the-art replacement mill near Hauser. Still, the mills’ departure would signal the end of Coeur d’Alene’s working waterfront, says Matt Tulleners, Stimson’s maintenance supervisor.

“When the mills are gone, people will pretty rapidly forget why this town was here. That’s the sad part,” he said. “All those new parcels are nice. Once it’s cleaned up, though, I won’t be able to afford any of it.”

From mills to health care

In the 1940s and 1950s, Coeur d’Alene’s waterfront was the heart of a timber industry that employed more than 3,000 people in Kootenai County. Gerald Sorbel was one of them.

Sorbel turned down the chance to attend the University of Idaho. In 1950, the 19-year-old’s dearest wish was to save $400 to buy his first car.

Northwest Timber gave him that opportunity. Sorbel’s starting wage was $1.35 an hour – nearly $11 an hour in today’s dollars.

“Almost everyone in Coeur d’Alene worked at a mill at one time or another,” said Sorbel, now 74. “In those days, it was a lot of hard work. People (who sorted lumber) on the green chain didn’t have to go to the health club. Some of those boards weighed more than 200 pounds.”

With a high school diploma, Sorbel advanced from the production line to sales and on to management. When Northwest Timber closed in 1990 he was the mill manager, overseeing more than 100 workers.

These days, Kootenai County’s fastest job growth is in health care, call centers and construction. Higher education is critical for advancement. And according to U.S. Census figures, individuals with a college degree earn nearly twice as much as people with a high school diploma.

“A college degree is an absolute necessity,” said Steven Peterson, an economics professor at the University of Idaho.

Stone wanted site in ‘70s

John Stone hankered after the Northwest Timber mill site for years.

The property first caught Stone’s eye in the 1970s, when he was a computer instructor at North Idaho College. Stone’s development career was just beginning. He bought up land with the profits from a programming business. Every other weekend, he skipped sleep and worked for 72 hours straight.

“I’ve never been afraid of hard work, and I was young enough to do it,” said the 61-year-old developer.

Ministorages were Stone’s early forte, and at one point, he pictured storage units along the water. Then the mill’s strategic location to Interstate 90, the college and Coeur d’Alene’s downtown began to sink in.

“I realized there was a higher and better use for the property,” Stone said.

By the time he bought the mill site in 1999, Stone had an extensive portfolio of West Coast projects, including nursing homes, midrise office buildings, and towers that blended retail and residential uses.

Stone designed his Riverstone development to tie into Coeur d’Alene’s resort character, with shops, a theater and public access to water. Taxpayers chipped in, too, with $1.5 million for streets, utilities and other public infrastructure on the old mill site.

Stone’s vision for the property included a physical connection to North Idaho College. He rallied community leaders around the idea of an “educational corridor.” They started dreaming about a higher education campus expanding west from NIC – through the DeArmond mill site – and connecting to the University of Idaho’s branch campus and Stone’s development.

The idea languished for lack of funding until this spring, when Chesrown announced that he had a working agreement to buy Stimson’s two mills. “Picture two years from now how this will all look,” Chesrown said. “You’re talking about changing the whole landscape of the city.”

The transition on Coeur d’Alene’s waterfront mirrors change across the West, said Todd Johnson, a partner in Design Workshops. Chesrown hired the Denver firm to draw up a master plan. Design Workshops specializes in creating urban centers out of old industrial sites, particularly rail yards.

In Coeur d’Alene, trains from four railroads once roared down to the waterfront, dropping logs in the water and whisking away the finished lumber. “It was the lifeblood and the highest-energy place in the city,” Johnson said.

Reconnecting the riverfront to the college and downtown will create a new energy, he said. The focus will be on intellectual resources.

“Now, some of the most important resources are human resources, and natural resources in the form of scenery,” Johnson said. “We’re becoming an idea-driven economy.”

From hobo camp to family campouts

The public’s views of the waterfront changed with the years.

To Don Pischner, who grew up in Coeur d’Alene during the 1940s and the 1950s, the waterfront was fascinating and forbidden territory. “There were lots of ways to get into trouble,” said the former state legislator, who’s now Stimson’s special projects manager.

The Spokane River’s glassy surface masked dangerous undertows. Down by the railroad tracks, pockets of pine trees concealed vagrant camps. And beyond Military and Park avenues – where the town’s leading citizens lived – the Fort Grounds neighborhood was known for its local toughs.

Parents were full of warnings, often ignored. Pischner knew a girl who drowned in the river, and once, while delivering newspapers, he dove in to pull a submerged boy out of the water.

“Hobo Jungle” was also off limits, but intensely attractive to curious kids. Pischner and his friends couldn’t resist sneaking down to the camps, lingering to listen to the stories of the men cooking dinner over open fires.

His forays to Coeur d’Alene’s piers were parent-sanctioned, but no less colorful. Henry Anderson, who owned an excursion boat, invited neighborhood children to come along when he delivered mail and groceries to lake homes.

Pischner also spent hours in the shop of a cigar-smoking boat builder named Bob Yandt, watching him apply coats of varnish to his latest creation.

“I have this huge attachment to that era in my life and those people,” Pischner said.

Pischner doesn’t begrudge the waterfront’s extreme makeover. Years ago, piers were surrounded by floating debris and sunken hulls. It wasn’t a place where locals took out-of-town guests to visit or their kids camping.

This summer, Ron and Pam Nilson will pitch their tent along the river. Their 9-year-old granddaughter will join them for a campout. But there’s no hint of hobos here.

The couple own a lot in the upscale Mill River neighborhood, once part of the old Crown Pacific mill site. They’re excited about the new development on the water and the change in the area since 2000, the year they bought a business in Post Falls.

“Ten years ago, I wouldn’t have given a second thought to living in Coeur d’Alene,” said Ron Nilson, a former Seattle resident. “Now, this is my community, and I’m proud of it.”