Selling a life of luxury

When Marshall Chesrown bought 650 acres of forested land overlooking Lake Coeur d’Alene back in 1997, a few other developers told him he got taken.

Four thousand dollars per acre was a steep price to pay, they said, even for a pretty parcel with resident elk and water access.

“Everyone thought it was ludicrous,” Chesrown said. “I thought it was cheap.”

At a time when other developers were focused on middle-class subdivisions, Chesrown had a bold vision for the lake. His purchase became The Club at Black Rock, an exclusive, gated golf community where greens are manicured into pools of emerald velvet, memberships cost $100,000 and real estate starts at $1.5 million for a stone-and-timber “cottage.”

The car dealer-turned-developer is reshaping how the Inland Northwest perceives waterfront. Once the domain of summer camps, family cabins, and an occasional estate, waterfront is a commodity increasingly associated with luxury. Sales of waterfront properties priced at $1 million-plus have tripled over the past year in Kootenai, Spokane and Bonner counties.

Black Rock is modeled after resorts built by Discovery Land Co., a San Francisco firm with an international reputation for high-toned golf communities in the Bahamas, Mexico, Arizona and California. Thirty percent of Black Rock’s clientele is local. Other prospective customers – usually referrals – fly in on the company’s private jet and are feted at the Coeur d’Alene Resort.

“We really don’t want them to come unless they can spend two or three days here,” Chesrown said. “What we’re selling is the North Idaho lifestyle … the lakes and the weather.”

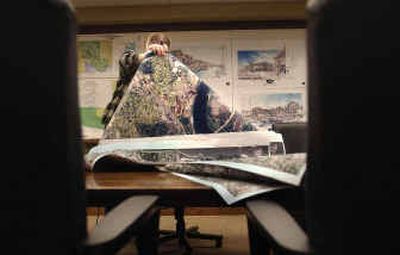

For Chesrown, there’s plenty more product to sell. The 47-year-old developer has amassed more than six miles of waterfront property in the past decade. The “war room” in his Coeur d’Alene office is awash with drawings and plans: a 1,200-acre addition to Black Rock that will include another golf course and an equestrian center; condos and townhouses along the Spokane River in both Coeur d’Alene and Spokane; estate lots on the lake; and 22 townhouses in a gated community near Huetter.

Not all of the projects have Black Rock’s exclusivity. All of them, however, are waterfront, or water view. “You won’t see me on the Rathdrum Prairie building subdivisions,” Chesrown said.

“He seems to have a better understanding of the intrinsic value of the place,” said Kootenai County Planning Director Rand Wichman. “We’ve kind of been selling the area short for a number of years. Maybe what Marshall has done is wring the untapped potential out of the area.”

Demand for luxury homes is rising nationally, fueled by a growing number of affluent Americans. The number of households with more than $1 million in assets increased by 14 percent between 2003 and 2004.

The Dallas-based Institute for Luxury Home Marketing assembled a profile of U.S. households owning at least one home valued at $2.5 million or more. Most were top corporate executives or business owners who made their own fortune. Nearly three-quarters were age 55 or younger. More than 70 percent played golf.

The trend toward luxury development disturbs some long-time Lake Coeur d’Alene residents.

“The ones he’s promoted to are the rich ones from California and Arizona. They pay outrageous prices for lakefront property,” said Jim Peplinski, who owns a lake cabin on Rockford Bay.

Peplinski and his wife, Elaine, bought their modest, two-bedroom cabin and 65 feet of waterfront property nearly 40 years ago for $21,000. It was a weekend getaway from the long hours that Peplinski put in as owner of Spokane Machinery, and where the couple’s three daughters learned to water-ski.

The cabin was valued at $265,000 on the Peplinski’s most recent tax bill, a rise the couple attributes in part to its proximity to Black Rock.

Tranquility on the lake is disappearing, they said. The influx of new residents creates more noise and congestion. “He lowers the lake style that the original residents are used to,” Peplinski said.

Chesrown said he’s not unfeeling to those concerns.

“I can be sympathetic with people who don’t like growth,” he said. “I live in Harrison, Idaho, because I like the rural lifestyle. But they’re coming whether we want them to or not. To the high-end real estate people, we are definitely discovered.”

Chesrown surprised other developers again with prices on two recent acquisitions. He paid $14 million for 25 acres on the Spokane River in Coeur d’Alene. He later bought the Summit property, an old rail yard overlooking the river in Spokane, for nearly $13 million.

Chesrown has a word for skeptics: waterfront here is still cheap.

“If increased property values bother you,’ he said, “you’d better start preparing.”

From cars to lake property

Chesrown sports a buzz cut, goatee and a down-to-earth demeanor. In full, his resume reads: developer, car dealer, former drag racer and high school sax player.

At 18, the Spokane Valley native rode his motorcycle to San Diego with $120 in his pocket, where he took a job selling cars to raise money for college. In three months, he earned $19,000. Chesrown never did show up to claim his music scholarship at the University of Arizona.

His mom, a retired teacher, hounded him about it for years. But she gets a new car every year for Christmas.

At age 28, Chesrown bought his first dealership in Boulder, Colo., which grew to a franchise of dealerships grossing more than $300 million annually. In 1997, Chesrown sold out to Republic Industries’ AutoNation, the nation’s largest automotive chain. He walked away from the deal with more than $70 million in stock.

Back in the Inland Northwest, Chesrown bought 650 acres on Lake Coeur d’Alene from a prominent Spokane Valley family, the Prings. Natural basalt outcroppings had given the place a name – Black Rock.

The Prings had always planned to build a golf course there, but Chesrown fancied the land for a private ranch. He was showing a real estate pal the location for his house and barn when the friend turned to him and said, “You know, this would make a great golf course.”

Early retirement was grating on the self-made millionaire. He took the comment as a sign.

“Business is business,” Chesrown said. Instead of cars, he had lake property to sell.

Chesrown, who doesn’t play golf, scoped out private golf clubs across the U.S. He was surprised at the success Discovery had in far-flung locations, such as Iron Horse Golf Club in Whitefish, Mont. The club is five hours from a major airport, and distant from services.

“God forbid if your wife wanted to have her nails done,” Chesrown said. “I thought, if this works in a place like Whitefish, my lord, what would it do in Coeur d’Alene?”

Since 2000, 260 of the Black Rock’s 350 lots have sold. The development’s success bucked the prevailing belief that only homes priced at $100,000 to $150,000 sold in this market, Chesrown said. Legacy Ridge, an upscale subdivision in Liberty Lake, had similar success, he said. The 165 lots in the subdivision’s first phase sold out in 45 days.

“He’s a master marketer,” said John Beutler, owner of Century 21 Beutler & Associates in Coeur d’Alene. “He’s done an incredible job of bringing people in from outside the area.”

Duane Hagadone, owner of the Coeur d’Alene Resort, was the first person to market the area nationally, Beutler said. “His focus is to bring people here for conventions. Marshall’s emphasis is to bring these people here to buy.”

Hagadone, a Chesrown supporter, remarked on the men’s differing styles in an October interview.

“We are total opposites in the way we operate,” Hagadone said. “Marshall buys and sells. Hagadone buys, holds, accumulates, develops and improves.”

‘Legacy’ comes up in conversation

Black Rock cultivates word-of-mouth advertising. New members spread the word at their other golf clubs. Referrals personally sit down to dinner with Chesrown.

He declined to speculate on the net worth of the club’s clientele. “I don’t ask them, but it’s high.”

One man spends $20,000 each month on private golf memberships. Another is building a $20 million home at Black Rock.

Later this year, Chesrown will submit plans to the Kootenai County Building Department for Black Rock’s 1,200-acre addition. He already owns the land. The second 18-hole golf course could be ready for tee times by 2007.

Discovery is also building on Lake Coeur d’Alene. Gozzer Ranch, a $100 million gated golf community, is planned to be built on an old homestead at Arrow Point. Chesrown welcomes their presence.

“Discovery is bringing a whole new group of very wealthy people to the area,” he said. “A lot of those people will buy a condo from us while their house is being built.”He sees the influx of wealth as only beneficial. Some homeowners will buy $100,000 worth of furniture. They’ll pay taxes, but use very few public services.

“If you’re going to have development, how could you want anything different? You know this is a Republican talking,” Chesrown said, “but it’s true.”

Chesrown bankrolled Black Rock’s first phase himself. He has a 20 percent silent partner in two upcoming projects – the Riverwalk condo development in Coeur d’Alene, and the Summit property in Spokane. He uses bank financing for other projects.

Chesrown’s portfolio is taking a different turn with the Riverwalk and Summit projects. Both are urban developments, reclaiming industrial sites on the water for residential and retail use. Unlike gated Black Rock, gawkers will be welcome. Public space is a cornerstone of both developments.

Riverwalk, built on part of a former sawmill site, includes a public boardwalk along the Spokane River, retail shops and a pond for ice skating in the winter. Chesrown envisions an eclectic mix of people living in the 412 condos, lofts, townhouses and single-family homes.

“For that type of living, people like the energy of public spaces,” he said.

His concept is similar for the Summit property, a former rail yard that will be developed into an urban village on the edge of Spokane’s West Central neighborhood.

“We’re dealing with legacy properties, properties that will make a long-term impact on the area,” he said. “Outside of a condemnation, it’s rare that you get a chance to redevelop 80 acres on the water.”

“Legacy” is a word that crops up in Chesrown’s conversations. He has a clear vision of the legacy he wants his developments to leave.

“Hopefully, it has the remembrance of quality, and reflects our policy of doing things right the first time,” he said.

“In 20 years, I guess I hope they still respect me.”