Returning with pride

COLUMBIA, S.C. – Former Wake Forest star linebacker Bob Grant recalled the death threats, the precautions to avoid violence on bus rides to Southern football stadiums and the harsh, volatile words spoken by opposing coaches.

That kind of discrimination motivated Grant and teammates Kenneth Henry and William Smith to call themselves the “Junior Jim Crow Killers” in 1964 when they showed up at Clemson’s Memorial Stadium for a freshman game.

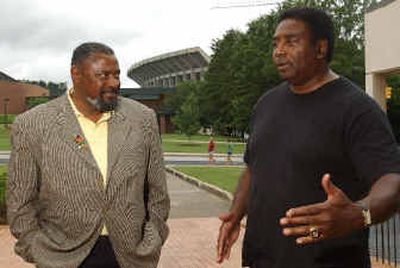

More than four decades later, Grant, Smith and former Demon Deacons basketball prospect Jim Carter – Henry died in 1996 – return to campus to support the “Call Me MISTER” program based at Clemson and designed to guide black males into teaching positions at South Carolina elementary schools.

“If you would’ve told me I’d be doing anything for Clemson, I would have said, ‘Fat chance,’ even if there was a gun to my head,” said Grant, one of the first blacks to play at Death Valley.

Grant never set out to break any color barriers. He accepted a scholarship from Wake Forest simply to pursue his goal of making the NFL.

“I had my own plan. I didn’t need an organization to speak for me,” he said. “Of course, you are aware of what’s happening and aware of what the contribution was.”

But the defensive star who played in two Super Bowls for the Baltimore Colts took extra pleasure in playing well against teams in the South, where many coaches claimed they would never allow a black player on their team.

“Quite frankly, it never changed in my four years there,” he said. “I don’t think I played against another black player until my senior year. That’s because there were none.”

Smith remembered a few negative calls from fans that day at Clemson.

“We knew we were going into hostile territory,” he said. “But we were fortified with our relationships with one another.”

A native of nearby Greenville, Smith could not wait to return home to play at Death Valley. But as a member of Baha’i Faith, Smith said he was seen embracing fellow members of the religion, black and white, before the game. That incensed his coaches, already fearful of racial tension, who made him stop and didn’t let him play in the game.

Grant said he, Henry and Smith were the subjects of violent threats “in a time when people could carry them out.” Black players were seated on the aisles during bus rides from hotels to stadiums, so as not to provoke attacks from people outside.

His effects, though, were made on the field. Grant recalled how, a few years later, Clemson All-American offensive tackle Wayne Mass came up to shake his hand and said Grant was the best ballplayer he ever faced.

The late Clemson coach Frank Howard also held a respect for Grant – and told the player so several years later when the two were at a fund-raiser.

Howard said to Grant in his gruff, Southern voice, “Back when you were playing, you thought I didn’t like you.”

Grant told him he thought Howard’s opinion was even worse than that.

“No, it’s not,” Howard responded. “I wanted some colored players, too. I was really glad to see you out there. One day, Clemson is going to have plenty of colored players.”

“Now,” Grant said, “when I see Clemson and Florida State take the field, I feel so fulfilled. … What we did was absolutely worth it. Forget the Super Bowls, forget the NFL. That was the best thing I ever did.”