Ban would show smokers the door

OLYMPIA – Last year, anti-smoking groups got a humbling lesson in how hard it is to get an initiative on the ballot. Their proposal to ban smoking in all indoor public places started late and fizzled out, starved for cash and netting fewer than half the needed signatures.

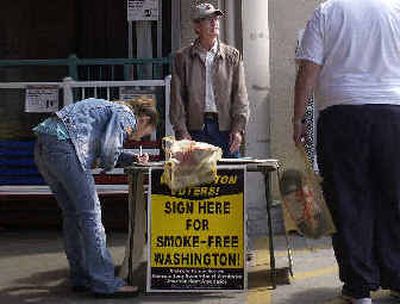

That’s not going to happen again, proponents vow. They’re back this year with the same proposal, this time backed by $300,000, broader support and better organization. With seven weeks left before the July 8 deadline, they say they have more than half the necessary quarter-million signatures.

“I will guarantee that we will make the ballot this year,” said Peter McCollum, who’s running the statewide signature drive for Healthy Indoor Air for All Washington, the group behind Initiative 901.

The measure would eliminate indoor smoking in public places that were exempted from 1985’s Clean Indoor Air Act. No longer would restaurants, bars, taverns, bowling alleys, skating rinks and card rooms be havens for folks wanting to light up. Smoking also would be banned within 25 feet of the doorways, windows and air intakes of public places.

“We citizens have a right to breathe clean air. They don’t have a right to smoke in our presence,” said Tedd Nealey, a Cheney farmer and substitute teacher who has gathered more than 2,000 signatures. “The burden should be on them to step outside.”

In Spokane, restaurant owner Bob Materne worries that his customers will step outside – and then keep walking. Making smokers light up outside may work in California or Arizona, he said, but not in subfreezing Spokane winters.

“If they walk out the door 25 feet, they’re going to get in their car and keep going,” said Materne, who’s owned The Swinging Doors bar and restaurant in Spokane for 24 years.

He predicts that his smoking customers will go straight to tribal casinos. As sovereign nations, the tribes wouldn’t have to comply with a state smoking ban. Restaurants already squeak by on a razor-thin profit margin, Materne said. Many won’t be able to survive the loss of their smoking clientele.

“A smoking ban does not cause smokers to quit smoking. It just causes them to go somewhere else to do it,” said Linda Matson, a lobbyist who battled last year’s measure. “You effectively give the tribes a monopoly on smoking areas.”

Proponents of the ban are confident that if they can get the measure before Washington voters, it will pass. McCollum said his group’s polling in December suggested that 59 percent of voters would vote yes.

“Every state’s doing it,” said Materne. “I know it’s coming down the line. I just don’t like the fact that Big Brother is doing it. It (smoking) is a personal-rights issue. This is not something that should be dictated to us.”

Already, 476 of Spokane County’s restaurants are smoke-free, according to the Spokane Regional Health District. That’s nearly 70 percent.

Anti-smoking groups have tried for years to get lawmakers in Olympia to pass a ban, but have been stymied by resistance from the industry and from a few key lawmakers.

“The problem with the Legislature is that it just takes one or two people to hold something up,” said Nealey, who spent two years trying to convince lawmakers.

He cites Rep. Bill Grant, D-Walla Walla, whom people on both sides of the issue describe as a staunch foe of a smoking ban. Grant’s campaign-finance records show that over the past five years, he has received thousands of dollars from Philip Morris USA, R.J. Reynolds and the state restaurant association. He could not be reached for comment.

Proponents of the ban paint it as a worker-rights issue. For 20 years, office workers have been protected from secondhand smoke. Left unprotected were the people in exempt businesses, like waitresses, bartenders and card dealers.

Matson maintains that there is little evidence that secondhand smoke is harmful. Federal workplace-safety regulators have repeatedly done workplace testing and been unable to prove harm, she said.

“Yeah, it stinks, but it doesn’t hurt you,” she said.

However, the Environmental Protection Agency has estimated that secondhand smoke causes about 3,000 lung cancer deaths in nonsmokers each year, according to the EPA’s Web site, and the National Institutes of Health have listed it as a known human carcinogen.

Businesses opposing the ban are now scrambling to put an alternative, I-911, on the fall ballot. Gary Murrey, who operates four Great American Casinos in the Puget Sound area, filed a measure that would ban smoking in areas where children are allowed. But it would allow smoking to continue in bars, taverns, non-tribal casinos and other no-kids areas.

“As long as smoking is legal in this state, there should be a place where adults can go and enjoy that legal activity with friends,” said Murrey.

His goal, he said, is “to go toe-to-toe at the polls.” Given a choice, he said, voters will choose the more modest restrictions.

“I think people believe that this is America,” he said. “You have a right to choose where you work and where you play, and not have a nanny state tell you what you can and can’t do.”