Family diagnosis

Dads are supposed to be trailblazers for their kids. They show them how to shoot a basketball, fix a car and pitch a tent, and then watch as their young protégés mimic their moves and eventually surpass them.

But Eric Highbarger wouldn’t have wanted his sons to follow his lead after colon cancer sent his trail on a detour.

Wesley, 13, and Blaine, 14, watched their dad lose and gain weight. They saw him learn how to eliminate his waste in a bag attached to his body. They saw the side effects of chemotherapy, a stew of drugs that simultaneously treats and terrorizes the body.

Then, after he battled the disease for six years, Wesley and Blaine saw their 35-year-old dad die in February.

So when Deanna Highbarger brought Wesley, 13, to a gastroenterologist last month as a precaution, her heart broke for her adopted son and his deceased father.

“I was floored when they showed me pictures of (Wesley’s) colon,” Deanna said. “It looked exactly like Eric’s.”

The teenager’s colon is littered with pre-cancerous polyps. Polyps – small mushroom-shaped growths – were also found in his esophagus.

On Thursday, Blaine went for his colonoscopy. The results are similar: thousands of polyps line his small and large intestines, she said, although there are none in his esophagus.

Although it’s not known yet whether Blaine’s polyps are pre-cancerous, Deanna feels certain that Wesley’s colon will have to be removed, a possibility the younger brother shrugged off at a recent Shaw Middle School baseball game. He was more interested in talking about his brother’s inability to remember the words to songs, about his girlfriend, Michelle, and about his grandmother’s boyfriend, Mike Reynolds, who sat beside him in a fold-out nylon chair.

“My grandma won’t marry him until he starts using his money wisely,” Wesley joked.

“That ain’t going to happen,” Reynolds bantered back.

Deanna and Eric met more than 10 years ago, when she was a student at Gonzaga University and he was her boss at her part-time job at Rite Aid. Eric was seven years older, separated from his wife, and a father.

“We had no business ending up together, but we did,” she said, adding that his sense of humor drew her in.

In 1995, shortly after Deanna and Eric met, the boys’ mother, Brett Michele Highbarger, died in a car accident. The couple married in 1997, and Deanna finished her degree in political science.

Law school was Deanna’s ultimate goal, so she enrolled in Gonzaga’s program. Then, while she was studying one day in 1999, Eric showed up at the library.

“We need to go to the doctor,” Deanna recalled him saying. “It’s serious.”

Soon enough, Deanna had the meal schedule at Sacred Heart Medical Center memorized. Family reunions were held in the Highbargers’ small living room so Eric could attend. The couple took their last outing together in 2004: a ride up the Space Needle in Seattle to celebrate Valentine’s Day, a holiday they usually spent with the boys.

Deanna always planned to adopt the boys, but the process accelerated after Eric’s death. At 29, she officially became the mother of two teenagers the day before her husband’s funeral.

“C’mon, buddy,” Deanna cheered for Blaine as he went up to bat during the Shaw baseball game. Coaching him from the stands is tough because she doesn’t know what to tell him to improve, she said. That was Eric’s job.

A week after the game, Blaine traded his baseball uniform for a hospital gown. Reclining in a hospital bed at Sacred Heart, he played Nintendo to take his mind off the pending colonoscopy – an uncomfortable procedure many adults avoid.

A colonoscopy is performed by inserting a flexible tube, or colonoscope, into the rectum. The scope allows doctors to see the inside of the large intestine and part of the small intestine.

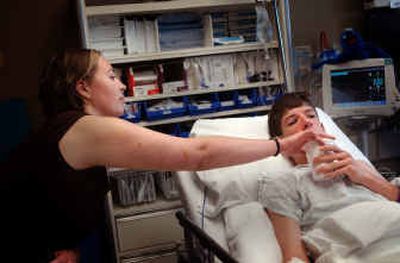

A half-hour before Blaine’s colonoscopy, he looked apprehensively at a needle that would insert a catheter into his arm so that fluids and a sedative could drip through his body. Deanna reminded him that his dad had IVs inserted dozens of times.

“Yeah, but he had bruises,” Blaine recalled.

Dr. Klaus Gottlieb, a gastroenterologist with Sacred Heart, said that when a person has familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), as Eric did, their offspring have a 50-50 chance of having it too. FAP is a syndrome that causes polyps and is responsible for only 1 percent of colon cancers.

A blood test can determine whether family members have the mutated gene that carries FAP, ruling out family members who don’t have it and avoiding unnecessary colonoscopies, Gottlieb said.

“You can imagine when you start screening a 7- or 8-year-old (with colonoscopies) how traumatic that can be,” he said.

On average, children with FAP develop polyps at age 16, but they will appear in 15 percent of children with the syndrome by age 10. For that reason, screening is often started at age 8 for children with the gene, Gottlieb said.

When the Highbargers learned that Eric had cancer, they froze a sample of his sperm in case Deanna ever wanted to carry their child. But after they learned that the cancer was genetic, they opted against the risk.

Deanna and the boys will fly to Nebraska on Thursday to see an expert on pediatric colon cancer. Their gastroenterologist, Dr. Linda Muir, recommended seeing the doctor before decisions are made about removing the boys’ colons, Deanna said.

Because of the financial strain Eric’s condition put on the family, the boys are covered by state medical insurance. The program won’t pay for the doctor’s visit in Nebraska until the boys see four specialists in Washington. But Deanna doesn’t want to wait that long, so she’s paying for the doctor’s visit herself.

A program called Miracle Flights for Kids is covering their airfare, and the Highbargers will stay at a Ronald McDonald House for free. To cover the doctor’s bill and other expenses, Shaw Middle School students and staff raised $5,000 in the last two weeks.

“They have very generous hearts,” teacher Becky Orchard said of the students. “If that’s the major lesson they walk away with, then that’s going to take them a long way in life.”

Like Eric, Deanna’s life has veered off course. Because he needed 24-hour care, she was never able to put her law degree to use. After his death, she began making plans to find work.

Now that the boys are facing medical problems themselves, Deanna will hold off on pursuing a job. Instead, she’s volunteering for a federal judge to refresh her skills.

Through it all, the Highbargers have kept their spirits up. They’re supported by a network of friends and family, many of whom took turns watching Wesley and Blaine when their parents couldn’t leave the hospital.

“There’s not much you can do. You can mope about it and be miserable,” Deanna said, and she and Eric saw plenty of patients with that attitude throughout Eric’s care. “But it takes too much energy to be like that.”