Idaho to get machines for voters with disabilities

BOISE – Every polling place in Idaho will have a pricey new handicap-accessible voting machine by early next year – regardless of whether it gets used.

“We’ll have at least one of those in each polling place,” said Idaho Secretary of State Ben Ysursa, with a likely total price of close to $5.5 million. The money’s coming from the federal government through the Help America Vote Act, which also requires states to develop statewide voter registration lists by Jan. 1.

Ysursa and county election officials around Idaho are worried that some of the sophisticated machines may just sit idle, gathering dust between elections and perhaps not being used even on Election Day.

But Kelly Buckland, executive director of the State Independent Living Council, said, “I don’t think you have to have a certain number of people who can’t vote in the process before it becomes worthwhile. As far as I’m concerned, if one person is denied their constitutional right to vote and vote in a private way, then that, to me, makes it worth it. And you have people right now who are blind or visually impaired who don’t have the same level of access to the voting process that everybody else does.”

Ysursa said he wishes the money could go to help disabled Idahoans every day of the year, rather than just for election equipment. “But ours isn’t to question why,” he said. “We have the money, and we’re going to proceed and follow the law.”

Idaho has close to 1,000 polling places. In Kootenai County alone, there are 71. Kootenai County Clerk Dan English said he’s still trying to figure out how and where the county will store 71 of the delicate 60- to 70-pound electronic voting machines between elections, how the machines will get out to polling places each time and get set up, and who will handle technical support.

“The feds did this, and they gave out one-time money … but all of the ongoing maintenance costs, storage and all that, that’s up to the local jurisdiction,” English said.

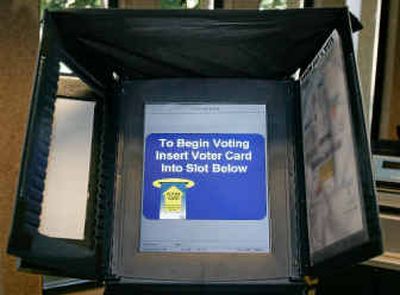

The new voting machines are designed to accommodate people with disabilities such as visual impairments and physical impairments that prevent them from marking or punching a ballot. One feature allows a person with limited movement to blow into a tube to indicate a vote.

Buckland said preliminary results from a new statewide survey conducted by his agency and Boise State University show that about 37 percent of Idahoans have a disability – up from 20 percent in 1995. And 76.3 percent of the disabled respondents said they had voted in the past two years.

“That’s significantly higher” than the general population, Buckland said. “Not only is there a high percentage of people with disabilities in the state, but as a group they are much more inclined than the general population to vote.”

That 37 percent breaks down into 13.4 percent who have difficulty walking or can’t walk, 9.7 percent who are deaf or hard of hearing, 7.2 percent missing a limb, and 7 percent blind or visually impaired.

The survey also asked disabled respondents if their polling places accommodated their needs, and an overwhelming 87.1 percent said they did. “That’s pretty high,” Buckland said. “So you’ve got arguments from both sides, as far as I can see.”

Two machines are being studied for use in Idaho now.

One, called the “AutoMark,” fits in with the optical scan ballots in use now in 14 Idaho counties, including Kootenai County. Those ballots typically are marked by filling in an oval next to the name of the candidate of choice. With the AutoMark, the ballot is fed into the machine, and headphones, audio instructions and Braille-marked controls allow someone who can’t see to mark their own ballot. The machine actually fills in the ovals.

“The idea is to let them vote independently and in the same manner as other people,” Ysursa said.

The other machine under review in Idaho is a touch-screen machine that also has an attached printer to print out a paper record of the vote. Idaho passed legislation this year – unanimously in both the House and Senate – to require such paper records when voting is done on electronic touch screens.

“Basically without a paper trail, there’s no tangible way to audit an election,” said Jim Mairs, Help America Vote Act coordinator for the Idaho Secretary of State’s Office.

Idaho isn’t alone in wanting paper records. Twelve states, including Washington, Montana and Utah, have passed similar requirements, and 26 more are considering them.

Buckland and others tried out touch-screen machines at a certification hearing last week. “It works pretty well – it was easy to use,” he said. As a wheelchair user with paralysis, he said, “I can use the punch card, but it is not easy to use it. This would make a big difference for me. … And for a lot of people who have even more significant disability than me, who can’t use their hands or their arms, then the machine would definitely work much better for them.”

Ysursa said the state will certify machines that meet federal requirements and comply with state law, and then let counties choose which ones they want to use.

In some of Idaho’s least-populated counties, the machinery is a far cry from what’s long been used for elections. “We’re still on a paper ballot,” said Rollie Bennett, Camas County clerk. “We’ve got about 800 registered voters.”

In fact, 16 Idaho counties still use old-fashioned paper ballots, which are counted by hand. They include Benewah and Boundary counties in North Idaho.

Camas County has two precincts, so it’ll have to set up two of the new accessible voting machines. “My personal preference was I’d just as soon stick with the paper ballots there and we don’t have to put up with the storage,” Bennett said. “But on the other hand, it don’t sound like we’ve got much choice.”

Two or three voters a year ask for help voting in the county because they’re home-bound or bedridden, Bennett said, so election workers go out to their homes and bring them their ballots. Others take advantage of “curbside assistance,” and have election workers come outside to their cars with the ballots.

“We also have absentee ballots, so they can request it and we just mail it to them. That way they can have somebody, a family member, give them assistance with it.”

He added, “Personally, we’ve got something that’s already working there. I don’t know why they’re pumping that much money into it.”

Ysursa said, “They’re going to need a $5,000 machine, two of ‘em, probably collecting dust. That’s what’s frustrating at times.”

Nationwide, he said, “Everybody’s scrambling. … There are some states saying, ‘I can’t get it done in time, you’re just going to have to sue us.’ Other ones are scrambling and are going to do the best they can. We have the money to do it, and we’re going to do it in partnership with the counties.”

Some states are consolidating precincts so they’ll need fewer of the new machines. But Ysursa said that wouldn’t be a good idea in Idaho, with its far-flung precincts in sparsely populated areas. “The bottom line in all this election process, as we know, is the voter – that’s who counts. If you consolidate precincts, you’re going to make it tough on the regular voter, who has to go farther to vote.”

English said he’s hoping to encourage Kootenai County voters to try out the new accessible voting machines, even if they don’t actually need them. “We could have 71 machines out there, and in my mind, it’s possible that maybe 40 or 50 wouldn’t get used,” he said. “We will encourage people to use them so that we have more votes on them.”

That’s the only way to see if the machines really work, English said.

He added, “For the people who truly need them, I think the machine is great. … But part of me wonders, for all of the time, money and effort, is this the best solution? But it’s something where we don’t have a choice.”

Buckland said, “These machines are specifically made so that they’re more accessible to people who have mobility impairment, but more so for people who have low vision and blindness. Think about that in regards to aging. Lots of people start losing their vision.”

He added, “If you live long enough, you’re going to get a disability. … I think that the need for these machines is only going to get greater.”