30 years later

In the summer of 1975, Bruce Springsteen was nobody’s Boss.

His nascent career was crumbling, just another over-hyped “new Dylan” about to get dumped by his label. Two of his band members had recently quit.

The bearded bard of the boardwalk was wrestling with his third (and last?) album, obsessively rewriting the lyrics and rearranging the music, spending an outrageous six months on a single song.

Yet Springsteen remained sustained by a lonely but ambitious vision, convinced he could re-create the little symphonies echoing through his head for an audience of millions around the world.

He was right.

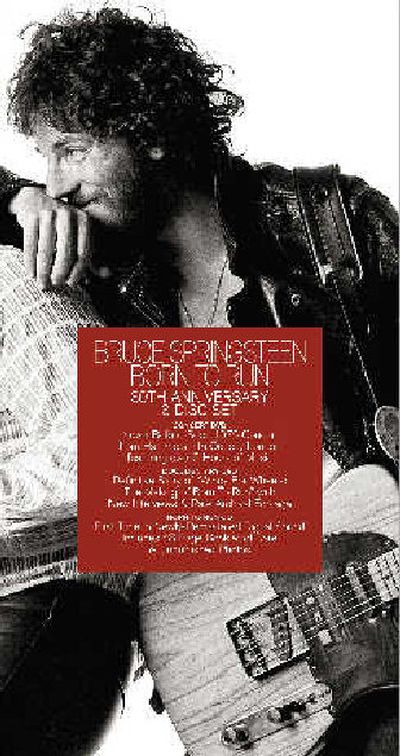

“Born to Run” was released in August 1975, a rock ‘n’ roll masterpiece that assumed near mythic proportion.

Thirty years later, as a special anniversary edition of the album was readied for release Tuesday, Springsteen recalled how making the record consumed his young life.

“Everything I knew and dreamed about was packed into those songs,” Springsteen said. “I had the desire to be great, to do something passionate, to capture something about living that I was yearning for myself.

“I wanted the whole thing.”

He got it, from the opening notes of “Thunder Road” to the album-closing epic “Jungleland.” But little came easy as he chased an elusive sound that was part Roy Orbison, part Phil Spector, and all Bruce Springsteen.

For Clarence Clemons, sax player for Springsteen’s E Street Band, that meant 16 straight hours creating the magnificent solo that anchors “Jungleland.”

For “Born To Run,” the single that announced the album’s arrival, sessions stretched out over half a year.

“I was 25 years old, with no place to go and nothing to do – that helped,” Springsteen said of his slavish musical devotion.

“We worked, and worked, and worked. It was very frustrating. But in the end, luckily, all of everything we did ended up in there.”

In a documentary DVD accompanying the remastered “Born to Run,” band members offer their recollections of the often fruitless recording sessions.

“Everyone remembers the experience quite truly,” Springsteen said with a laugh. “And everyone was centered around this thing, that we suffered. No one forgot that. Everyone had that in common.”

They all shared another thought: Springsteen, child of the Jersey shore arcade, was going for the brass ring this time.

“I knew, because I knew the songs, that this album was going to be phenomenal,” said “Born to Run” co-producer Jon Landau, who eventually became Springsteen’s manager.

“I knew Bruce Springsteen’s determination. I knew there was no way it was going to miss in achieving its musical goals.”

Even if, in Springsteen’s mind, those goals often remained unreachable despite hundreds of hours in the studio.

“My obsessive/compulsive nature, which crippled me through much of the rest of my life, does come in handy once in a while,” said a chuckling Springsteen. “And it came in handy at that moment. I wanted something unique that you couldn’t hear in the live show.”

The process produced some laughs, too. The “Wings for Wheels” DVD offers a full recitation of how Springsteen pal Little Steven Van Zandt, dressed like a New Jersey gangster in a zoot suit and fedora, walked into the studio and sang all the horn parts on “Tenth Avenue Freezeout” to acclaimed session musicians Randy and Michael Brecker.

Album engineer Jimmy Iovine recalled not even knowing who Van Zandt was, but thinking that Steven “was dressed like a guy” who knew about horn players.

After “Born To Run,” Springsteen wound up in a protracted legal battle with his first manager; his follow-up album, “Darkness On the Edge of Town,” didn’t appear until three years later.

By then, the sprawl and bombast of “Born to Run” was in Springsteen’s rearview mirror, never to return on record.

Springsteen, in fact, confessed that he hadn’t listened to the album in two decades until earlier this year.

“I thought I knew exactly how it would sound, but it surprised me,” Springsteen said. “It was a nice moment driving back from the city, and it caught me by surprise again.

“There’s no other record (of mine) quite like it … I never made another one.”