Remembering the forgotten

No one came when they died.

No one claimed them after their bodies were found on the streets of Spokane.

Now buried in the Garden of Peace, a potter’s field at Holy Cross Cemetery, these homeless men and women were mourned Friday during a memorial at the House of Charity.

“We needed to do something to remember all the people who have died on the streets,” said Rob McCann, executive director of Catholic Charities. “Our whole community needs to remember them in their death, and also how they lived.”

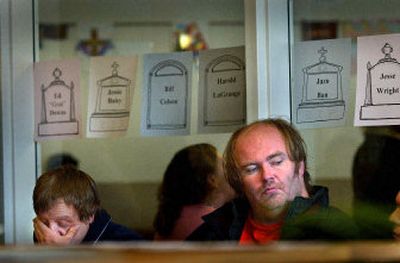

About 30 people, a few with tears in their eyes, crowded into the small chapel of the downtown shelter to memorialize about 70 men and six women who have died on Spokane’s streets in the last 10 years. “A Memorial in Honor of Those Who Have Gone Before Us,” stated the plaque on the altar table, placed in front of a wooden sculpture of Jesus on the cross.

On the chapel’s glass walls, pieces of paper with pictures of tombstones contained individual names.

Ed “Goat” Downs. Jessie Baty. Bill Colson. Harold LaGrange.

While a few suffered violent deaths, some died because they were sick – diabetes, seizures, illnesses that could have been treated with regular medication and visits to the doctor.

Willie Castama. Vern Berg. Lovie Divesbackwards.

Some died of drug overdoses. Others froze in winter.

In the months, perhaps weeks before they died, nearly all of these individuals ate a meal or found a bed at the House of Charity.

“That could’ve been me,” said Jeffrey Logan, who has been coming to the House of Charity for the last four months. Homeless off and on for the last 12 years, the 41-year-old recalled his own troubles on the street – the threats to his life, the beatings, the challenge of finding shelter during winter. “It’s tough out there. It’s easy to go down and really hard to get back up.”

Ed McCarron, director of House of Charity, knew almost every single one of the people whose names covered the chapel walls. He recalled how some of these guys used the phones at the downtown shelter to call their children. He remembered how many tried to find jobs and get their lives back together.

For the memorial, McCarron put the list of names together using the House of Charity database. But even without help from the computer, he could’ve written them all down from memory, he said. He knew them that well.

It’s hard to keep track of the people once they stop coming to the House of Charity – which last year served more than 70,605 hot meals, provided free emergency medical care to nearly 1,800 people and sheltered 724 different homeless men during the winter. But McCarron usually learns about a death when he gets a phone call from police or the county’s medical examiner’s office.

“I think it’s important that people don’t judge the homeless by what they look like,” said Robert Dean, a U.S. Army veteran who has been coming to House of Charity for the last four months. “Things happen after traumatic experiences. … Look at how they got there. They didn’t start out like this.”

Since the Garden of Peace was established two years ago, the Catholic Cemeteries of Spokane has accepted the unclaimed cremated remains of the deceased at the Spokane County medical examiner’s office. Twice a year, the medical examiner’s office brings the remains to Holy Cross, where they are buried in the Garden of Peace. There’s no service, no music, no flowers. But each person’s name is carved on a 6-by-6-inch granite headstone.

“I’m aggravated to see so many people gone,” said Scott Stanger, who has been living on the streets for four years.

Many homeless people don’t have families in town to help them, so they consider their fellow transients their family, he said.

During the memorial, Stanger spoke about some of the people whose names were on the wall – guys who just needed a break, men he knew by their street names.

Cincinnati. Mad Jack. Goat.

“I don’t want to see one more name on that list,” he said, shaking his head.